|

Sometimes aspiring writers think having an author read their manuscript will give them a head-start on getting published. They may be setting themselves up for disappointment, for several possible reasons… 1. Just because someone is published doesn’t mean they have any special knowledge about what “the industry” is looking for. They submitted a specific manuscript which caught the attention of a specific editor. Good on them, but this doesn’t necessarily imbue them with special inside information regarding “who’s looking for what.” 2. It also doesn’t necessarily make them a reliable judge of good writing in general (whatever that means). Secret hint: writers frequently like writing similar to their own. Thus, asking one to read and respond to your manuscript can result in them critiquing your work into a junior version of theirs. (As discussed earlier.) 3. There may be a misconception that an author can somehow fast-pass your manuscript by giving it directly to her editor. Sorry, but 99% of the time it just doesn’t work that way. The few times I’ve seen an author pass a friend’s manuscript along to her editor, in every single case the friend was left waiting around for a response for as long—or longer—than if she’d submitted via the usual channels. Editors aren’t just sitting around waiting for good manuscripts to drop in. They’re inundated with them, receiving them daily from professional agents who actually know what a solid, commercial manuscript looks like. And of course they also receive manuscripts from their existing authors, who likely already have a track record regarding quality and/or sales. All of which isn’t to say “The odds are long so give up now.” Not at all. I believe a great manuscript will eventually see the light of day, with enough hard work and persistence. My point is, having an author say, “Here’s a manuscript from my friend,” is not a direct path to publication. (TL; DR: An actual agent who’s putting her professional reputation behind your manuscript will carry much more weight with an editor than a pass-along from “a friend.”) 4. If said author “doesn’t like” your work, what’s your course forward from there? Are you supposed to revise it to be more like their work? Are you supposed to throw it away and start over? Are you supposed to get depressed and quit writing altogether? (The real answer, of course, is: D, none of the above. You should probably let it go and move on. Unless their critique rings true with you, in which case revise accordingly and then move on.) 5. However, even if said author “loves” your writing, unless their last name is Patterson or Rowling or King they’re probably not in a position to offer you representation and/or a publishing contract. The people who can do this—whose opinions matter to you in the first degree—are agents and editors. These are the people you should be trying to get to read your manuscript. And the best way to make this happen, in short, is: (1) Have a great manuscript—finished, re-written, revised, polished, and totally-ready-for-primetime. Then, (2) contact an agent who’s represented published works similar to yours, using a brief, intelligent, non-sociopathic query letter letting her know what you’ve written and why she might be a good fit for it. Repeat until you achieve the desired result. Note that this will require a little research on your part, but not an impossible amount. And don’t get too cute with the query. Remember, you cannot talk someone into liking your manuscript. You can only write them into liking it, by doing a bang-up job of actually writing it, and by not submitting it until it’s as good as it can possibly be. But you can easily talk them into not liking it. Hence not getting too clever with the query. There is something an author can do which may be more useful to the aspiring writer than simply reading their work, which is to pass along whatever small bits of wisdom they may have about writing and the publishing industry. I’m happy to speak with writers’ groups (and have done a bit of it, both on book tour and locally) and of course I also try to throw out helpful tips here, FWIW. More than once aspiring writers have contacted me and basically said, “Can I buy you a cup of coffee and pick your brains?” And—if schedules align such that this can actually happen—it can be beneficial to the aspiring writer, likely much more so than simply having someone read and comment on their manuscript. I recall one smart young guy who lined out the basics of his just-completed book, then asked, “What would you do next, if you were me?”, which led into a good discussion about how to (and how not to) go about acquiring an agent within his specific genre. When we were done he thanked me for my time and I thanked him for not asking me to read his manuscript. He laughed and said this was a way better use of his time.

0 Comments

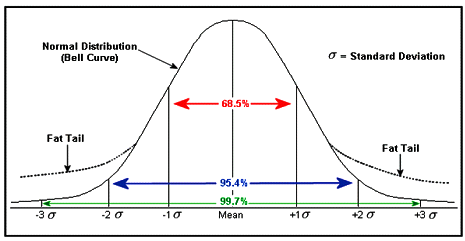

Last time we discussed counting words, and whether it helps or hinders or has no real effect at all. (Short answer: All of the above. Depending on you, your project, and your goals. And, of course, the KUWTJ factor*. But under no circumstances is it unconditionally required.) (*Keeping Up With The Joneses.) And as I mentioned, there doesn’t seem to be any obvious correlation between counting and quality, either way. But there is a related factor that actually does seem to affect quality. And that’s pace. In endurance running, there are two ways to screw up a marathon. (Well, there are actually about two million, but we’re only looking at two here.) One is to try and run faster than your optimum pace. And the other is to run well below it. Both will leave you feeling not-so-good, in different ways. And—interestingly enough—both will almost certainly result in a longer finish time than if you’d just found your sweet spot and maintained it. And both result from the same thing: fear. Fear of not keeping up with someone else (or maybe with someone else’s perception of you) which leads to exceeding your optimum pace and blowing up before the finish line. or… Fear that maybe you can’t really do what you actually can (aka fear of failure) which leads to self-doubt and dropping back to “protect yourself.” Guess what? Both of these can apply to writing, too. With this in mind, there are some fundamental concepts regarding pace that might be useful for writers to consider, especially with book-length projects: 1. Your pace is your pace, and no one else’s. It’s not a race (even if others think it is). When you let your pace be dictated by someone else, you’re playing their game. Your goal isn’t to “beat” anyone. It’s to do the best job you can while writing, and feel good about the result after you’re done. (In other words, pace affects both process and result, so no matter which is more important to you, it matters.) 2. Know your pace. This doesn’t come from adopting someone else’s pace or from reading about it on the internet or from what an instructor thinks it should be. This comes from experience. Real, practical, empirical experience. But maybe you haven’t written a novel yet? That’s okay. After you’ve written a bit of it (say 10,000 words or maybe three or four chapters), you’ll have a pretty good idea of what works for you if you’re paying attention. 3. Try to maintain your average pace, within reason. What you’re really looking for is the macro of overall time (as measured in months or years, which we’ll talk about in a minute) as opposed to the micro of words-per-day. And keep in mind: faster is not necessarily better. Better is better. 4. But be flexible about it. Pace is a tool, nothing more. And it’s your friend, not your master. Some days, writing just may not be in the cards for you. Or maybe some weeks, or some months. I’m not talking about making excuses for why you haven’t touched base with your story in forever. I’m talking about those times when life legitimately intrudes, and you either can’t write, or writing might not be the best use of your time at the moment. Don’t beat yourself up—we’re humans, not machines. And even your favorite authors have times when writing is the last thing on their mind. My overall hypothesis about the macro of writing pace for book-length projects: Each of us has an “optimum overall writing time” for the completion of a novel. (This can apply to any big project, but we’re going with novel as the desired outcome here for simplicity’s sake.) And this time can and will vary—greatly—between different writers. And this time can also vary between different types of projects. And this time is not a specific value, but a range—a broad range. And it’s actually more important to know the dangers of being too fast or too slow than knowing your exact optimum writing time. As follows… Too fast: Ideas are like seeds. They can grow into wonderful plants or trees. But before they grow, they have to germinate. And occasionally we’ll get an idea we’re excited about, and without really playing it out in our minds and considering different iterations, we just jump right in and start writing. (I’m guilty here, too… I’m about 60/40 pantser, which doesn’t excuse a lack of basic pondering before committing words to paper.) This can result in one of the more painful aspects of writing: going back to the beginning and starting over. Or—almost as painful—a major structural rewrite. Either way… ouch. Also, sometimes when a writer has an idea and a basic outline and then just cranks the book out, there can be a lack of interesting subplots or three-dimensional characters or maybe just the subtle literary subtext that can give a work more depth. And more often than not, this seems to occur when the author is pushing for speed and maybe writing faster than usual, whether due to internal pressure or external deadline. Too slow: When talking to writers groups, questions about writing schedule invariably come up. And my usual response is, “Everyone is different, with different lives and different priorities. I think you should determine what works best for you and do that.” Because I’m the last person to tell someone else exactly what they should do. The writers - online or at conferences - who stand up and pontificate things like [insert deep announcer voice], “You need to write for an hour every day before work,” are basically talking to themselves. However, I’ll sometimes add, “My only recommendation is that I think it can be helpful to write regularly… for whatever value of regular works for you.” This has nothing to do with the speed at which you crank out words, but everything to do with keeping your subconscious engaged. I’ve said before I think it’s pretty clear the subconscious does a lot of the creative heavy lifting when it comes to story creation. (Which is why it’s almost universal for writers to get ideas while showering or running or driving or washing the dishes or some low-concentration activity that distracts us just enough to let the subconscious come out and play.) But for this to happen, that part of our brain needs to be engaged on a regular basis so it continues to “work” on the problem even when we’re not consciously thinking about it (similar to thinking about a problem before going to sleep and having a solution upon waking). And the way you feed your “creative problem-solving mechanism” (i.e. your subconscious) is to connect with your story regularly. Ideally this involves actually writing on it. But even if you can’t write, then editing or plotting or just re-reading the last few chapters will keep the story in your head and encourage your subconscious to keep working on it behind the scenes. This really seems to increase the odds that next time you sit down to write, you’ll have something worth writing about. This is harder to accomplish if you only touch base with your story once a month or whatever. For me, whenever there’s been a long gap between writing sessions I have to spend quite a bit of time just getting the vibe of the story back in my head. (This seems especially true when it comes to getting the voice right.) So besides basic production issues, there seem to be some real creative benefits to working on your story regularly. The Sweet Spot: If you graphed my writing with “Overall Writing Time” on the X axis and “Subjective Quality” on the Y axis, the result would look pretty much like a standard bell curve. The curve would first start to sweep up at around the six month mark and taper back down near the eighteen month mark, with the sweet spot for overall writing time (everything from initial conception to plotting to writing to revising to polishing to final copy edits) hovering around the twelve month mark. The actual values are meaningless for anyone but me (and you’re missing everything I’ve ever said if you think you should somehow try and approximate them) but the concept remains: Our creative minds seem to have a natural cruising speed they like to function at… thinking and digesting and regurgitating and writing and thinking some more and writing some more then re-thinking and subsequently rewriting, etc. We can certainly work faster than our natural pace (just ask anyone who’s ever had a demanding supervisor) but the results are rarely optimum. And it’s all too easy to work slower (just ask, well… anyone) but here, too, you’re probably not thrilled with the final result, let alone the lowered productivity. Your sweet spot may be six weeks or six months or six years. (And it may vary with your experience level and mood.) The specifics aren’t important. What is important is to be aware of it and—as much as possible—honor it. But don’t over-think it. After all, the goals are pretty simple: 1. Get to the finish line. 2. Be happy with the result. I’ve read so much recently—on blogs and forums and social media—about how many words per day people write... or think they should write... or wanted to write but didn’t. (Followed by the inevitable self-flagellation if they wrote less than their friends or less than their predetermined goal or whatever. There is definitely a certain amount of FOMO going on here—there’s even an online business seemingly dedicated to nothing but selling a program guaranteed to up your daily word count well into five figures.) Personally, I never think about my daily word count one way or the other. I write until I run out of time or juice, then I move on to something else (maybe cogitating on my story while doing other tasks). And more to the point, I know authors with dozens of books to their name (award-winning, best-selling books) who feel—and do—likewise. I’m not saying don’t try to hit a predetermined word count each day. If that somehow motivates you to do quality work, then by all means, count away. But please don’t think it’s required that one count words in order to be a writer*. Imagine the following: An agent or editor receives your manuscript. She reads it, and her overall impression is, “Not bad, but not really what I’m looking for.” She gets ready to send the usual boilerplate “thanks but no thanks” response, but then she sees your small, handwritten note at the bottom of the last page: By the way, I wrote this in a month. Does she (1) scream “Stop the presses!” and instruct her assistant to offer you a contract post haste, since anyone who wrote even a mediocre manuscript in 30 days must be a hell of a writer? Or does she (2) give a bemused WTF? shrug and send the “no thanks” response anyway? (If you live in a universe where you believe there’s even a remote chance that #1 is a plausible response, please remove yourself to a soft room with padded corners.) Obviously if/when you get to the point where you have contracted work under deadline, you need to work diligently and make your deadlines. But even then, you’re not going to be required to write anything like several thousand words per day for several weeks or months straight. I recently read an interview with a very popular and beloved children’s author where she said she’s only good for about one decent page (approx. 250 words) per day. Any more and she feels her quality suffers. Even at this relaxed pace, she finishes a middle grade manuscript in seven or eight months. (Typically a best-selling, award-winning manuscript, so we can assume her publisher is just fine with her current word count.) The lesson here isn’t “only write a page a day.” (Which makes no more sense than saying, “You must write ten thousand words per day.”) The lesson is that steady, sustained work, over time is what leads to the completion of a manuscript. Regardless of your words-per-day pace. And if a page-per-day is enough to complete a million-seller in less than a year, then your actual daily word count is likely not an issue. So when might we want to count words? It can be helpful if you need external motivation to keep writing. If you find yourself regularly stopping after twenty or thirty minutes, for example, it might be useful to make a deal with yourself on the order of, “I’ll write until I hit (insert magic number here), then I’ll let myself stop for the day and do something else.” Do this every day for a couple of weeks and it should condition your brain to want to create during your writing time (which is the actual goal, of course). If this still doesn’t solve the motivational issue, you might want to look elsewhere. (Regarding that “elsewhere”… Your mileage may vary, of course, but I’ve learned that when I don’t want to sit down and write, it’s usually because I’m unclear as to where I want to go with the story and I need to do some more planning/plotting/pondering before actually writing. If I forced myself to write another couple thousand words in these cases, they would almost certainly get deleted next session. When I know—at least roughly—where I want to go, I find myself wanting to write, and need no other motivation than to want to see the story unfold before me.) Again, I’m not saying don’t count your words. I’m saying no one else (no one who matters, at least) cares how many words you wrote today. What they care about is the end result—did you create a wonderful manuscript they love and enjoy and want to represent or publish? If yes, then they offer you representation or publication. If not, then they don’t. Period. So yes, absolutely count words if doing so leads to you creating the sort of work that will garner you representation or publication or critical acclaim or best-selling status or whatever particular gold ticket you have in your sights. Then, of course, there’s the issue of doing writing work that doesn’t involve initial draft creation. In other words, rewriting. (Or revising or polishing or any other level of self-editing.) This often accounts for a substantial amount of the actual work involved in creating a strong manuscript, yet how do you quantify your progress when you’ve spent several hours immersed in the manuscript with a net result (word count-wise) of zero, or maybe even the loss of several hundred words? Does this mean you didn’t have a productive day? On the contrary, these can be the days that do the most to improve your manuscript, yet you’d never know it if all you go by is the total number of words generated. In studying this phenomenon I haven’t noticed much of a direct correlation between word count and writing quality, but I have stumbled onto something interesting with regards to the whole quantity/quality issue which I’ll dive into next time. In the meantime, count—or don’t count—as you see fit. But either way, don’t worry. Be happy. Write. *WRITER: One who writes. (Notice there’s a period after that definition, not a comma.) |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed