|

There’s a long-standing theory that writers shouldn’t talk about their WIPs because that’ll take away their desire to write it, or interfere in some way with the creative process. I’m calling BS on this. Having said that, I’m not one to publicly talk about works I’m planning to write, nor do I advocate doing so… simply due to common sense cart-before-horse reasons. In my casual observation, there’s a pretty solid negative correlation between those who do the above—typically on social media and typically in bemoaning fashion—and those who actually finish/revise/polish/publish their work. Although my business-whiz son would be the first to say, “Dad, correlation—in either direction—is not causation,” so technically we’re not sure if blabbers don’t finish or finishers don’t blab. Either way, I’m not taking any chances… However, I have a countervailing philosophy that says there can be a significant creative benefit to discussing your works-in-progress, assuming it’s done in the right way with the right person. (The not-right person is the one whose first reaction is to immediately tell you exactly what's wrong with your idea and how they’d improve it, etc. Life is rough enough without voluntarily pulling on that specific hair shirt.) But… When you're on page 281 of a 400 page novel and you find yourself holding a couple of competing ideas in your mind, it can be very helpful to run them by someone who knows how to listen and can help you brainstorm in a positive fashion. The other person may likely be a writer but they don’t have to be. The more important part is that they read widely and thoughtfully, and are capable of putting their emotional responses to story ideas into words. Spoken words. (And of course the most important factor is that they adhere to the Prime Editorial Directive™: Help the writer write THEIR book as best they can.) Really, it’s much more of a gentle back-and-forth exchange—like a lunar-gravity ping pong match with a nerf ball—than any sort of critiquing session. You’re looking for the “Yes, and…” kind of response vs. the “No, but…” type. One benefit, of course, is simply getting another viewpoint (similar to what a beta reader does, but more “during” than “after”). And that’s great. But you also get something you don’t get from a beta reading—the real-time back-and-forth exchange of ideas concurrent with the initial creative process. You’re trying on ideas with your “pre-beta” without having to write them out first, and you can quickly pivot with a “…or maybe she does this instead of that” if you realize your first idea wasn’t quite right, and your brainstorming partner might reply with “…yes! And what if he sees her do it, but maybe she doesn’t know he sees her…?” to which you respond, “Yeah, and then he’d act differently toward her and she wouldn’t know why, but we would…” And so on. This can be an effective way to jumpstart your story elements (as well as a great time saver, since you’re essentially beta-testing without having to type it all out first), as long as you’re aware it also means you’re primarily testing plot ideas and not the actual writing itself. (For that, there’s still no substitute for someone reading the written words without any verbal input from the author, just to ensure everything in your head actually made its way to the page.) Another way this can save you time is what I call “rabbit hole avoidance.” Sometimes, having external editorial feedback during/before the initial drafting can spare you the heartache of throwing away large chunks of writing and starting over when you come to the astute conclusion that maybe you shouldn’t go down the whole “kill & bury the uncle” path in chapter 17… which is fine, except the epiphany comes a hundred pages later—in chapter 25—when you finally realize you could really use that uncle right about now because he’d be perfect for another idea you have. Damn. If only you’d thought of that earlier… And now for what may be the biggest potential benefit of “talking plot.” Talking about a creative activity seems to engage a different part of the brain than just silently thinking about it. I can’t count the number of times that simply outlining my plot issue verbally has led to me turning around and—again, verbally—solving it. Sometimes before having received any input from the other person. Not sure why this is so—maybe your mouth has a more direct connection to your subconscious?—but I’ve seen this work too many times to ignore it. Not all ideas put forth will be useful ones. That’s okay—poor ideas often lead to good ones, which is the whole concept behind brainstorming. Or as my wife likes to say, “Mark will come up with 99 bad ideas, but idea #100 makes it worth wading thru all the lousy ones.” (Usually followed by a snicker.) But again, much of this process is simply the brainstorming partner listening and making encouraging noises, then occasionally asking pertinent what-if questions. The main thing is that the designated writer in this scenario not make blanket “NFW” responses to any ideas, but listen and consider in turn. When this happens—on both sides—the end result is usually very positive and productive. The above is my experience. Everyone is different, with a different workflow, and this may or may not work for you. My only advice would be to try it and see. The next time you’re stuck in the sagging middle, instead of just putting your head down and grinding something out, consider bouncing a few ideas off someone else—ideally someone considerate and creative—and see if it sparks something. I’m betting it will. If you have any techniques you use to jumpstart your story-spinning, please share them with us in the comments.

0 Comments

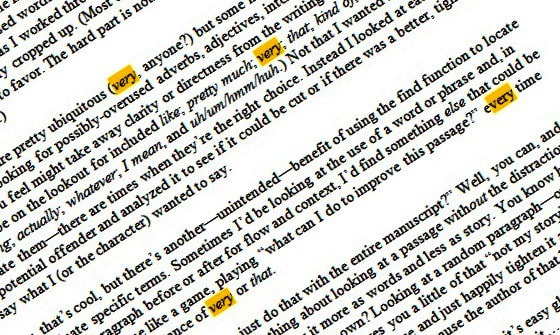

As an author, you’ll occasionally have people asking you to read their manuscript and provide advice. (Whether or not you should do this is a topic unto itself. Some established writers have a blanket policy against it for valid reasons, including the fact that it’s bad business to work for free. Others are happy to do it when time permits, paying forward the help they received as beginners themselves.) Often the person asking is an aspiring writer. Maybe a younger writer, or maybe a beginning writer—of any age—just learning the basics of the craft. Assuming you’re going to take on the task of reading their work and giving feedback, here are a few things to keep in mind: 1. Don’t step on dreams. This is the equivalent of the primary Hippocratic concept, “First, do no harm.” There are experienced writers who feel anything less than ‘brutal honesty’ is somehow beneath them. They think some people simply weren’t born to be writers, and the sooner someone tells these poor schmucks this, the better. Really? In reality no one actually knows who’s going to eventually—with enough sustained effort—become a decent writer. History is full of late bloomers who didn’t show much early promise. (The Big Sleep, anyone? Watership Down? Or how about Angela’s freaking Ashes—a first book that was published when the author was sixty-six?) And even if they never go on to become successful authors, they still receive the intangible benefit that writing gives everyone who puts pen to paper—the unique feeling of accomplishment in organizing their thoughts and setting them down in print. Some aspiring writers may never find success in publishing (however they happen to define it). But they may still get as much out of it—on a personal level—as a best-selling author. And on the Big Scale of Life, this might even outweigh the benefits of brutal honesty. Wheaton’s Law still applies. 2. Leave them wanting more. A good question to ponder when helping the new writer: “What single activity is most germane to becoming a better writer?” (Spoiler alert: the answer is writing. Followed closely by reading.) When my kids were young I signed up to coach my older son’s basketball team, along with one of the other dads. The players on our team were all good kids but were complete beginners. (And my buddy and I weren’t exactly John Wooden either.) We taught the kids basic b-ball skills as best we could, but during and after the games some parents would get down on their kids for not “doing better.” (Which is invariably fruitless. Everyone is doing their best in the moment with the tools they have. Which are not your tools.) In the end, I’d pull the more serious parents aside and bluntly explain the reality that our team was rather less skilled than the other teams, and my real goal for the year was simply that the kids enjoy the experience enough to want to continue playing basketball going forward. Because the only way they’re going to get better is to play more. A lot more. And for that to happen, they’re going to have to want to play. Artistic skill develops over years, not weeks. This doesn’t mean you can’t get real benefits from a few intensive weeks of writing and study, but most people who do typically have years of practicing their craft behind them. Can you imagine taking a complete non-writer and throwing them into something like Clarion? So the real objective here is simply to leave them wanting to continue writing. 3. Giving them a fish vs. teaching them to fish. What’s your overall goal when critiquing an aspiring writer? If it’s “make this specific story better,” then I suggest you take a broader view. Making a beginner’s story stronger is usually pretty simple, as the flaws are generally apparent. (Blatant exposition, unrealistic dialog, over-use of adjectives, inconsistent characters, telling us how a character feels instead of letting their actions reveal it, etc.) If you just line edit the heck out of it, it’ll almost certainly be a stronger story. But will they have learned anything about the craft of writing? (And—if you really do a deep-dive edit—will it even be their story when you’re done with it?) So consider helping more with overall craft than just working on specific story issues. I remember a friend coming to me with an article he wanted to submit to the local paper. One line he’d written was something on the order of “He was very, very tall.” Instead of simply slashing it and replacing it with “towering” or whatever, it was a great entrée into a discussion of intensifiers. Same deal with multiple descriptors. He was describing a woman who was “… warm, sweet, affectionate, and cheerful.” Instead of just cutting three of the four, I asked for an example of her behavior. He gave me one, and we talked about a way to fit it into the story instead of him just telling us how nice she was. You want to leave them with interesting things to consider, as you show possible paths to their goal. (As always, you want to help them write their story as best they can, not show them how you’d write it.) So don’t default to only showing what’s “wrong”. Think about it in terms of giving them options, and showing them why one option may be stronger than another. (This is really all about the “why,” right?) 4. Stay within their skillset, while stretching them a little. I’m a drummer, and occasionally give informal lessons to beginners. I don’t start by sitting down and demonstrating 4-way independence (where each limb is doing something different at the same time). That’ll either frustrate and discourage them or go over their head entirely. Instead I’ll ask them what they would like to be able to play on the drums, and I’ll give them something relevant to work on that they can’t quite do perfectly yet, but which is within their grasp. Closer to home, you probably don’t want to overload your beginning writer with a rundown of the nuanced differences between limited third-person, objective third-person, and omniscient third-person points-of-view. Find out what they wish to accomplish with their story, and try to help them get there with understandable advice that speaks to their current skillset. Example: If they’re using close third and are unsure about the mechanics, they can probably benefit from something like, “It might help the reader feel grounded if you stay in one character’s head throughout the entire scene or chapter.” 5. Catch them doing something right. This goes back to the concept of leaving them motivated to continue writing. It doesn’t mean being a cheerleader. It means striving to find some aspect of their work they honestly did well. If not in execution, then in concept. It could be a character that—at least at times—feels real and unique. It could be an interesting plot twist. It could be a bit of dialog that rings true. It could simply be a well-described breakfast at a funky little diner. Let them know you thought it was well done, and why. Encourage them to apply this technique to other parts of the story, if applicable. Writers have strong and weak points. That’s universal. What’s not so universal—especially with beginners—is knowing what your strengths and weaknesses are. So do them a favor and let them know what they do well. If they’re wise enough to take it to heart and capitalize on it, it can really benefit their writing going forward. And of course, hearing positive feedback about some aspect of their writing will only motivate them to keep trying. And that—sustained effort—is probably the biggest precursor to success of all. Sometimes there's a benefit to taking things out of context... I was revising a recent manuscript and I’d done pretty much everything you’d reasonably do—make notes about broad plot issues and tackle them one at a time; make sure your characters are self-consistent; ensure dialog comes off as realistic (reading aloud where necessary); make sure there are no continuity issues with times/dates/etc… all the way down to CE-level stuff, including grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc. Then I recalled that during the final round of editorial notes on a previous book, we looked at and addressed a few overused words or phrases. I thought, Why wait for an editor to tell me I over-use something? So as I worked through the manuscript I started jotting down repetitive phrases that occasionally cropped up. (Most of us have these little tics in our writing—words and phrases that we tend to favor. The hard part is noticing them, because they’re such a part of us and our vocabulary.) Some of these are pretty ubiquitous (very, anyone?) but some may be more unique to you. Either way, you’re looking for possibly-overused adverbs, adjectives, intensifiers, qualifiers, and anything you feel might take away clarity or directness from the writing. (FWIW, my list of things to be on the lookout for included like; pretty much; very; that; kind of; sort of; just; or something; actually; whatever; I mean, and uh/um/hmm/huh.) Not that I wanted to blindly eliminate them—there are times when they’re the right choice. Instead I looked at each instance of a potential offender and analyzed it to see if it could be cut or if there was a better, tighter way to say what I (or the character) wanted to say. This is where the “find” function is really useful: Think there might be a common term you’re abusing? Punch it in to find you’ve only used it seven times in three-hundred pages. Or perhaps seventy times. And maybe after you’ve found and addressed each instance, you see that you’re down to thirty. Then on to the next word… Okay, that’s cool, but there’s another—unintended—benefit of using the find function to locate and eliminate specific terms. Sometimes I’d be looking at the use of a word or phrase and, in reading the paragraph before or after for flow and context, I’d find something else that could be tightened. It became like a game, playing “what can I do to improve this passage?” every time I’d look at another instance of very or that. You might ask, “Why can’t you just do that with the entire manuscript?” Well, you can, and I did. Several times. But there’s something about looking at a passage without the distraction of the larger plot which enables you to view it more as words and less as story. You know how it’s easier to trim someone else’s work than your own? Looking at a random paragraph—out of the larger context of following the story linearly—gives you a little of that “not my story” mojo, where you see a slightly clunky or over-wrought phrase and just happily tighten it and move on… without worrying about the pain it might otherwise cause the author of that brilliant phrase. Also, when we’re reading the story for the tenth or twentieth time, it’s easy to glaze over the actual writing because we’ve seen it so many times that we become inured to it… we “hear” it in our head before we even see it on the page, and we discount little things that might otherwise trip us up if reading it for the first time. Addressing sections out of order and context lessens this “I know what’s coming” factor and helps give us a new perspective on the actual phrasing of the paragraph in question. In other words, it puts you more in the editor mindset and less in writer-mode, which is exactly what you want when you’re making revisions at the sentence level. So… seek & destroy with impunity. Your story will thank you. |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed