|

Among people training to run a marathon (especially those attempting to run one for the first time) there is a saying that carries a lot of wisdom: Respect the distance. (See here for a post about me literally applying this to a group of first-time marathoners… as well as to writers.) And all the clichés around this are true: A novel is a marathon, not a sprint. Take it one step at a time. Don’t think about the whole thing, focus on the work in front of you at the moment. Etc. But… “Respect the distance” also applies to the writing life in general. Which is funny in light of how “Get Published Now!” is also the flavor-of-the-month when it comes to hot aspirations these days… both IRL and on social. The irony is that if ever there was a long game, writing is it. It almost seems like the world’s worst activity to decide to “just do.” Right up there with “I think I’ll just buy a bassoon and be playing for the symphony this summer.” First off, there are all the years of pre-writing training you’ll need to do to avoid (a) reinventing the wheel, and (b) writing badly. This pre-writing regimen is sometimes known by its technical term: reading. (Writing without a steady diet of reading behind you is analogous to aspiring to be a musician when you’ve never listened to music.) Besides a background of reading broadly and deeply, you’ll also want to read pretty extensively in your chosen genre (which—if you’re smart—is also your favorite genre, so you may have a leg up on this). Then there is the small matter of learning the craft. I know we all learned how to put words on the page in grade school, but learning to write effective fiction is a completely different pursuit, similar to learning to play the violin or paint portraits or sculpt a figure from a block of marble. There is typically a lot of “student work” that comes before the work people will actually pay you for, and (if you’re like me or any other writer I know) you’ll likely end up writing a bunch of stuff that probably won’t see the light of day before you finally get a “yes” from an editor at a publishing imprint. All of which is fine, because that’s how we learn the craft—it’s our practice. But if we’re pinning our hopes on our first student-level efforts making publishers climb over each other for the chance to put us into print, we might end up a little disappointed. “Respect the distance” means respect the craft, respect the practice, respect the artform, respect the journey. And the best way to do that is to love the practice. Love the craft, the journey, the artform. Even love the distance. Imagine a young couple, getting married. They (hopefully) aren’t thinking, I can’t wait until we’re retired and we can do whatever we want. No, they should enjoy every day they’re together and view it as a gift. So don’t just focus on the destination. If we want to get there in one piece, with our artistic vision (and mental health) intact, we should do our best to enjoy every step along the way. Yes, it’s a long game. And it’s dead serious—at least at times—and hard work. But it’s also play… it’s art… it should be something we love. Being a writer isn’t something you do. It’s something you are. For the long term. Respect the distance.

0 Comments

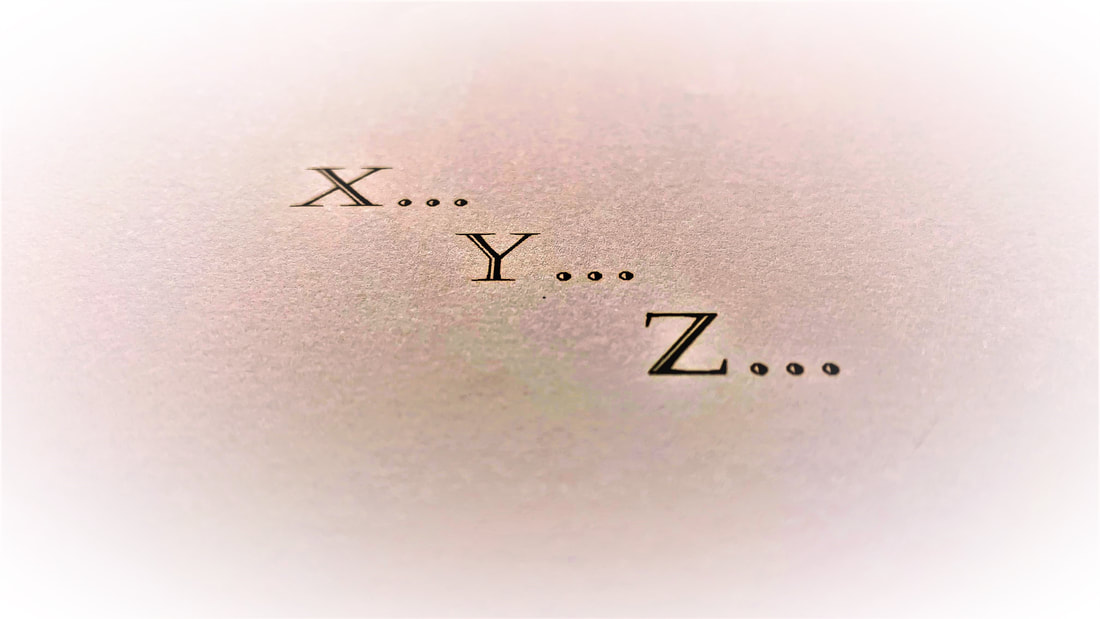

I may be shoveling sand against the tide here but there’s a pervasive paradigm within the writing-centric social media community that does a pretty serious disservice to aspiring writers. In short, there’s a lot of stress, importance, energy, time, and focus being put on things that aren’t primarily writing. When in reality… The way you get better at writing is by… writing. The way you create a strong manuscript is via writing. The way you acquire representation is through your writing. The way you get acquired and published is through your writing. What makes readers want to buy and read your work is… the writing. Man, it’s all about the writing. All those other things only come from the writing. That’s the place to put your focus… if you actually want to be a writer. (I qualified that statement because there’s a subset of people who want to ‘have written,’ and/or want to ‘have had a book published,’ for some imagined perks that have nothing to do with actually loving—and improving at—the craft of writing.) In this sort of environment, is it any wonder it’s easy for emerging writers to get distracted by all the non-writing aspects of the whole ‘being a writer’ thing? Your attention—your focus—is like the money in your wallet… you only have so much of it, and if you want to make it to the next payday you need to think carefully about where you spend it. I see people spending lots of time/energy/focus (and angst) on non-writing things like… Becoming ‘agented’… (Pretty sad it’s an adjective these days.) Being published… Doing book signings… Doing school presentations… Speaking at conferences… Winning awards… Making ‘Best of’ lists… Hitting certain sales numbers… These are all things a writer might do—on the periphery—but these things aren’t writing, and focusing on them won’t make you a writer. Only writing will do that. And—not coincidentally—the people who actually do the above things seem to be people who put the craft of writing above any sort of ego boost they might get from accomplishing those peripheral things. And, as nice as they are, those things aren’t even close to being the best part of being a writer. Writing is the best part. By far. If you don’t love the craft of writing—without any of the supposed perks—you’re likely to be sorely disappointed if you’re trying to acquire the “writer’s lifestyle.” So to those distracted/disappointed/depressed by all the current negativity on social around the whole subject of ‘being a writer,’ my best advice is to not waste any energy worrying about that crap and put your laser-sharp focus (and your time and your effort and your love) where it actually matters… on the craft of writing. The goal over which you have total control (and—in an interesting karmic twist—the one most likely to get you all those peripheral things) is simply to become the best writer you can, and to write the best book you can. Focus. You see a lot of posts on social these days from people spending a lot of time and energy trying to put together a pitch and/or query agents and/or land an editor & get a book deal, and a lot of words around how hard this all is*. [*Fair enough. It is hard, no doubt. But to put some reality around this perception, (a) I heard publishing guru Jane Friedman say on a podcast just this morning that there are more books being acquired today than ever before, and (b) it has always been hard—my wife had ten years of rejection over the course of three or four novels, and pretty much every published author I know (including yours truly) has a not-dissimilar story. So don’t lose sight of this amidst the current pub-doom scrolling.] But also, you see a lot of musing on whether or not it’s “worth it,” and whether or not they should keep doing it. On one level, the whole question is a self-correcting issue. I mean, if you want to do it, you’ll do it. If you don’t, you won’t. But this is simplistic, and avoids the real issue here: What is it you actually want to do? Not as a stepping stone, but as a terminal objective? Get an agent? Land an editor? Get a book deal? Successfully publish? Sell a bunch of books? Win a big award? Hit list? All those things largely depend on the decisions and tastes of someone else. Now, hypothetically, what if your primary goal was dependent on only you… what if your primary goal was simply to write the very best book you are capable of writing? Period. Not comma. What would you end up with? There are no guarantees of course, but if you really put your heart and mind to the above goal, there’s a reasonable chance you’d end up with… the very best book you are capable of writing. There are also no guarantees this would get you an agent and an editor and a published book. But if you were to get those things at some point, which factor would probably be more important… starting with a clever pitch, or starting with the very best book you are capable of writing? Not that your query doesn’t matter. Of course it does—you have to have that in place to get them to read your manuscript, so you obviously want to make sure it does its job. But even the best query in the world won’t make them sign a mediocre manuscript. One thing agents and editors say over and over: it needs to be good enough for them to “fall in love with it.” These words mean different things to different people, but one thing we can be fairly certain of—once you get their attention, everything else falls away and it’s all about the writing. The perfect pitch, the carefully curated mood board, the well-researched comps… they can’t help you at this point. They’re like an Uber driver who’s taken you to a job interview. They’ve done their job, and now it’s all down to the actual words on the page. Once the agent or editor starts reading your pages, all they care about is… does this have “it”? At this point, what you really want them to have in their hands is (wait for it…) the very best book you are capable of writing. And in my humble opinion, the way you get that is to focus on that—rather than the whole marketing aspect—until you’ve written and revised and edited and polished your manuscript (and probably beta/rev/beta/rev… and more polish) to the point where it represents the best work you can currently do. Even then, your agent (probably) and your editor (absolutely) will have multiple suggestions to make it even stronger. But they need to see the potential in your writing before you’ll ever get to that stage. And you can give that to them, by giving your writing the best chance to succeed. In light of all this, the “should I quit?” question doesn’t even come up. Quit writing? Why would you quit something you love, something you’re driven to do, something that costs nothing to do, something that no one is stopping you from doing? I can’t imagine that. Not if the goal is to write the best you can. But if the goal is something second-hand, then maybe so. Because when it comes to motivation, intrinsic beats extrinsic every time, hands down. In my admittedly-finite data collection on this, the ones who want to write… who need to write… are the ones with the best chance of getting published. Because they’re more likely to be doing the thing that editors want… they’re putting something on the page that means something to them… and thus it’s more likely to mean something to the reader. To put it in mathematical terms: The more you want Z, the less likely you are to get it (because you’re distracted from what it really takes to get it). But the more you want X and Y (the precursors to Z, namely: a burning desire to put words on the page and tell your story, and a long-term dedication to the craft of writing) the more likely you are to wake up and find Z pounding on your front door. Funny, isn’t it? Happy writing!

This is an interesting one. And possibly subject to misinterpretation. So let me say right up front that—in my opinion—self-belief (or any other phrase describing how we view ourselves and our place in the world) is important, and can affect how we navigate the world. But not for some mystical reason. In my view, this stuff works for reality-based reasons. Our brain is basically a machine that programs itself, constantly taking in whatever information is within grasp and using it to add to its programming. You can’t really stop the process, but you can help determine what you program it with. (This is similar to the “read good, write good / read bad, write bad” effect we discussed earlier, where what we put into the process helps determine what comes out. Or, as my dad used to say, “Garbage in, garbage out.”) Critical to understanding this is grokking that parts of our brain literally can’t tell the difference between truth and fiction. (Here’s the easy proof: Have you ever been scared by a movie? Sure. And yet, in the middle of the film, if someone were to stop the projector and asked you, “How was this created, and is it real?” you’d answer, “Those are actors, on a sound stage, surrounded by a crew of technicians, being filmed as they say lines written by someone else. It’s complete fiction.” And yet… a good horror film can scare the crap out of you. Because that emotional-response part of our brain believes what gets fed into it, and responds accordingly. Without regard for the “truth or fiction” aspect of it… assuming it appears enough like truth to not throw us out of the story.) So, on some level, parts of our brain tend to believe what we put in front of it. Which is why visualization is now an integral part of virtually every serious athlete’s training… if for no other reason than the pragmatic fact that it just works. Same for self-talk or affirmations or anything else of that nature. Just recently I heard a best-selling author describe—in a podcast—her little informal writing group’s methodology. In brief: the writers (all novelists) bring a couple of pages from their WIP, they read them before the group, the group responds with positive feedback, and… that’s it. Done. No “Here’s what’s not working” or “Here’s what I would have done” or “Why did you do this?” or “Instead of doing that, why don’t you…” or critical commentary at all. After describing their method, she laughed and said, “I know it sounds silly, but it works.” It didn’t sound silly to me at all… it sounded brilliant. These aren’t beginning writing students (in need of the fundamentals), these are experienced novelists. Who have figured out that the most pragmatically useful thing to them—in the middle of drafting a novel—is simply holding the belief that they’re doing good work. Period. Sure, there’s always a time and place for looking at things with a critical eye. But in the middle of the slog, thinking that all this work is worthwhile… that it’s adding up to something good and special and valuable… is critical. Otherwise you’ll likely never finish. Because it’s hard to do good work if you don’t believe that you’re capable of doing good work. And if you don’t think you can do it… you probably can’t. Because you’ve convinced that part of your brain where emotional decisions are made that you can’t do it. But what if we did the opposite? What if we fostered an emotional belief, deep inside, that we were capable of good work, if only we applied ourselves to the point of completion? The odds of us finishing at all—let alone producing something good—just went up exponentially! It’s not some woo-woo mystical thing. Yes, you still have to have the goods (and/or do the hard work of turning the not-so-goods into the goods, which is how virtually all writers do it). But that can come after you’ve finished the initial marathon of getting those 100,000 words onto the page. In the middle of the march, you need to believe that you can do it. When people talk themselves down, I sometimes say, “Be careful what you say, because someone’s listening… you.” There’s a fascinating little story around the shirt in the photo (which was given to me back when my first novel was published). I’ll let you deduce your own version of it (and put it in the comments if you like) because (a) you’re a writer and that’s what writers do, and (b) I don’t want the synchronicity of it to detract from the overall message… To wit: How you think about yourself—and your work—matters. Don’t stop believing! Many of us have certain things we like to do while writing, or maybe it’s a certain place or a favorite sweater or certain music or snacking on certain foods or… (Personally, I can’t write without some sort of beverage—usually caffeinated—sitting next to me.) I suppose you could make the case that a writer should be able to write anywhere, at any time, while eating/drinking anything… or nothing, and while listening to anything… or nothing, and while wearing…. you get the point. I humbly disagree. Or at least, I don’t think the best way to approach an act of creativity is to force it under unfamiliar circumstances. I have a theory that humans enjoy having certain things or conditions around them while doing creative work because these familiar things—these rituals—prepare the mind for whatever comes next. They serve as reminders… they say to the brain, it’s time to write (or paint, or exercise, or eat, or sleep, etc.). Or maybe they simply give us the message, This is a safe place… it’s okay to relax. Like a child having their favorite stuffed animal when going to bed. Or maybe just having the familiar is good because it’s, well… familiar*. [*My wife used to have a watch which—for some inexplicable reason—always started beeping at 8:00 a.m. Even with the alarm mode off. Every time it happened, we’d look at each other and laugh. “It must be eight o’clock!” She finally replaced it… and immediately missed the friendly little “enjoy your morning!” reminder. So instead of getting used to a correctly functioning watch, she set her new watch to alarm each morning at 8:00. Just this morning, we were most of the way through our weekend long run and feeling a bit pooped, when it went off. We both laughed and said, “Must be eight o’clock!” and got a little lift from the friendly reminder. I mean, why wouldn’t you want that?] So if there are certain things that make you feel creative or mindful or relaxed or just plain happy… don’t be afraid to incorporate them into your writing routine, regardless of the location or circumstances. We might have to get a little creative or be a little flexible, but there’s usually a way to make it work. Example: my favorite thing to listen to when I write is… nothing at all. Not that I don’t love music. Actually it’s the opposite problem—I get involved in the music to the point of distraction. Same with nearby conversation… I find myself actively listening (as writers do), trying to make sense of it… trying to fit it into some sort of story line. But sometimes I like to leave the confines of the quiet office and venture out among the rest of the human race. Like at, say, a nearby coffee shop. So I bring my silence with me… in the form of earplugs. It really helps with concentration to be able to block out most of the outside noise. (Some people use earbuds and leave them unplugged, which both blocks some sound and gives the impression you probably don’t want to be interrupted. And of course, if you can’t write without your death metal blazing away, crank it up and crank out those words!) I also like those coffee shop paper cups, and I used to take them home and drink coffee in them during writing sessions until they fell apart (usually within a few days). I finally broke down and bought the reusable plastic version. So now—assuming I don’t come too far out of my writing-induced trance and actually look around the room—I can sort of maintain that coffee shop vibe when I’m chained to my office desk*. [*Speaking of coffee, my wife isn’t the coffee hound I am, but I’ll occasionally make her what I call a “sidewalk latte” as a mid-day pick-me-up. Just a really small straight latte, maybe with a biscuit. The first time I did it I put a tiny spoon next to the small cup just for fun—like at a sidewalk café—even though she doesn’t take sugar. But from then on, I have to include that demitasse spoon. Because it gives her a certain vibe. Which I guess is the whole point of this post…] So whatever it is that gives you that “I’m in my comfy place, ready to create” vibe, I encourage you to lean into it. Being creative is hard enough (especially this year) and anything we can do to help send an engraved invitation to the muse is definitely worth doing. Happy creating! Once upon a time I managed to land an agent with my OBFN* and he dutifully shopped it around. After it had made the rounds at most of the bigger houses (some nibbles and close calls, but no solid “yes”), I asked him how I’d know when it was time to pull the plug. He said, “You’ll know it’s time when you just don’t want to do it anymore.” [*Obligatory Bad First Novel] At the time I thought that was sort of a glib answer, but I eventually came to realize the absolute wisdom of it. In theory we can agonize over it indefinitely, but in reality it’s a self-solving problem. As long as you have the belief, desire, and energy to continue shopping the project, you’ll keep shopping it. At some point, the desire fades and/or you direct your energy elsewhere, and you eventually stop shopping it. In many cases (including mine) you end up writing something new, and you focus your energy there instead. Which may be a good strategy regardless, since it’s likely to be a stronger manuscript due to you having the experience of writing the previous book. (Again, in my case, it was. I put the painful lessons I’d learned from that first failed manuscript to good use with my second one, and ended up placing it.) All of that’s fine, and in retrospect finally quitting on that first book and trying to write something better was the right choice for me (although it sure felt crappy at the time). In fact, I’d venture to say we all have projects, either whole or in pieces, sitting abandoned on a hard drive somewhere. Or maybe stripped and sold for parts (which is another post). Bailing on those projects is painful, but part of the bigger process. Sometimes we have to let things go so that we might move forward. I think we can all understand that. But sometimes, we might reach a point where we just want to stop writing entirely. Which—while being a different thing—is also understandable. Sometimes a break is the best thing for us, especially if we’re using it to recharge and not as avoidance. (I used to work with a coach who, in the middle of leading an intensive group workout, would sometimes call out, “Take a break if you have to, but not a vacation!”) Stopping is not quitting. Stopping with the intention of never re-starting is quitting. There’s a qualitative difference*. [*While in NYC a dozen years ago to run the New York Marathon for Exercise the Right to Read (a charity my wife and I started to help raise money for school libraries and to buy books for underprivileged children) we were also able to catch the U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials, which happened the day before on a course that consisted of several laps around Central Park. That was both an inspiring and tragic race, with many takeaways. One of the most instructive things I saw was late in the race, when one of the runners near the front of the chase pack pulled over and grabbed the chain link fence next to the path. “Oh man, he’s done,” I thought. I mean, why else would you stop running late in a closely contested race? But he wasn’t done. He clung to the fence, took a few deep breaths and stretched his leg, then pushed off and got back in the race. And finished in the money—somewhere in the top ten.] But maybe you’re not talking about bailing on a particular project, or even taking a break from writing. Maybe you’re contemplating quitting altogether. First things first: If you want to quit, you’re absolutely free to do so*. At any time. And you owe no one any sort of explanation or apology. [*Assuming nothing under contract, of course.] I could say lots of encouraging things, all of which I fully believe. I could tell you that “failure” is what “success” looks like from the middle of the process (which I’ve experienced firsthand more than once), and that virtually every published author I know swam through a lot of mud before finding clear water, and that collecting rejections is absolutely part of the game. (I’ve got quite the collection myself, and my wife faced rejection for almost ten years before a single “Yes!” wiped out all those “No!” responses and she went on to publish thirty-plus books—and counting—with a major publisher.) I could also tell you that your sticking point is likely either a process issue or a writing issue, and either way, it’s likely fixable. (Which is pretty much the entire reason I host this blog.) You might consider getting some help… some coaching… some outside input… to give you the “second set of eyes” that can be so critical in finding areas for improvement with either your writing or your shopping process. I could say all that, and more. But I also know that feeling like you’re beating your head against a stone wall without even a glimmer of a crack can be daunting. Maybe to the point of wanting to stop. Maybe forever. And if so, I’d be the last person to judge you for it. But maybe the thought of officially “quitting” depresses you, leaving you stuck between two bad choices. So maybe don’t look at it that way. Maybe look at it as a trial separation. Maybe try it for a while, and see how you feel. If you try it and you’re still good with not writing after several months, then you probably have your answer. If the relief—or the feeling of freedom or just the extra time for other pursuits—from not writing is worth more than the value you get from writing, then you may have made the right choice. If so, good for you, and best of luck at whatever’s next. But if not… if after a while you find yourself unexpectedly mulling over plot points and thinking of settings and—most especially—creating characters that you care about… that feel real to you, then there’s no law that says you can’t go back to writing. Remember: Home is the place where—when you knock on the door—they have to let you in. So… You can stop with a project that’s not working for you. You can take a break from writing if you need to. You can quit altogether if that’s what’s best for you. And you can always go home again. But it should be your choice, for your reasons. I think there are two fundamental truisms regarding writing: 1. You should never write because you feel like you have to, and… 2. You should only write because you feel like you have to. These may seem self-contradictory, but writers will understand... I think it’s important to take note of—and to celebrate—the little victories*. Including those in your writing life. (*The ones that mean something to you, I mean. I’m not always a big fan of participation trophies, especially for kids. Not that participation isn’t a good thing—it’s usually the best thing—but kids generally know the score. Literally as well as figuratively. I remember when our youngest was in a “no score” beginner basketball program. The theory: the kids play, they have fun, no one keeps score, and they’re all happy when it’s over. The reality: they all keep score on their own, and it freaking matters to them. Once after a game I told him, “Good game!” and he looked at me like I was an idiot. “What are you talking about? We lost, eighteen to eight!” **Storms off to retrieve his juice box and Lunchable**) But when you have a real victory—no matter how small—I think it’s good to commemorate it. When our oldest was a cub scout they had a little pinewood car derby. The kids all started with identical blocks of pine and they carved, sanded, assembled, weighted, tuned, and painted their cars. Other than discussing the importance of aerodynamics and reducing friction (he was a science guy even back then), I mostly just made sure he could use a power sander without hurting himself then let him get to it. He was pretty meticulous about the whole friction thing and on the night of the derby—after an hour of thrilling elimination rounds—he took first place. He was super excited about winning. Afterward, I was expecting some sort of trophy or plaque or whatever (these things always have trophies) but there weren’t any. On the way home I could tell my son was a little disappointed, but he didn’t say anything about it. So I went out the next day and got him one. Nothing fancy—just a basic little trophy with a race car on top and the words “First Place” on it. I didn’t get it so he would have bragging rights or anything (bragging wasn’t really in his personality, regardless). I got it because I think it’s good psychology to commemorate the little victories we occasionally have. It’s also nice to have a tangible reminder of the occurrence, so that afterwards when you look at it, all the good, fun, validating feelings you had at the time come back to you, reminding you… Yeah, I did that! In the writing world, these sorts of things come along all-too-infrequently. Even for the successful writer, a new book deal or a new release or hitting list or winning a big award doesn’t happen every day. Or even every year. And for those of us still upward bound on the ladder (i.e. virtually all of us) they happen even less often. So celebrate them. You don’t have to wait until the final end-goal is accomplished, either. You should celebrate the steps along the way. These may even be more important to recognize, because they’re the type of accomplishments that don’t usually garner outside kudos. (No one’s going to buy you an ice cream because a well-respected agent requested the first three chapters of your manuscript. So do it yourself.) Some little-recognized-yet-important milestones that warrant a celebration… You finish the first draft of a manuscript. (I told a writing friend once that I’d finished a first draft—he was basically a wise old cowboy type—and he said, “I’d think that might make a man want to open a can of beer.”) You finish all your revisions/edits/polishing and—for the first time—you think it’s finally submittal-ready. (This is a big one, as the most important precursor to publication is a strong, finished manuscript.) You do all your research and make a first-round list of agent candidates who represent works like yours, then you write/revise/polish your query letter and send it to them. (Oh yeah! Beer me! I put hope in the mail!) After a number of rejections, you get a request for a partial. (Yay! Someone’s reading! This calls for chocolate!) After even more rejections, you get a request for a full. (Yes! More hope! We press send and get ourselves a mocha!) I’m not going to follow this all the way to, You hit list, win a Pulitzer, and get your own imprint… all within the same month. Not just because those things don’t really happen outside of the movies, but because that’s precisely my point: if we wait until “The Big Win” to celebrate, most of us are going to be waiting a long time without commemorating all the incremental victories along the way. So don’t wait. Start now. Look for interim accomplishments that are steps along your path and give yourself a pat on the back for making that next step. The events certainly don’t need to be tied to the specific path of publication, either. If they further your writing knowledge, skills, or talents in any way, they’re candidates for celebration. Take a class on any aspect of writing? Celebrate! Teach a class on any aspect of writing? Celebrate! Present at a school, library, or writer’s group? Celebrate! Publish an article in a magazine? Celebrate! Write a piece for someone’s blog or podcast? Celebrate! Interview someone for a magazine, blog, or podcast? Celebrate! Get interviewed by a magazine, blog, or podcast? Celebrate! Self-publish your book? You’re a hero—celebrate five times! (Because you’ve just been an author, editor, art director, publicist, and sales manager!) Along with everything else, it’s good psychology. There’s nothing like a little positive reinforcement to keep us going. (And if you’re in need of external recognition, this can also serve to tip off your friends. “What’s up with all the wine and chocolates?” “Oh, that…?” *looks down shyly* “…I just finished final revisions on my contemp romance.”) So yeah, recognizing and celebrating those steps along the way can give us the motivation we need to keep going along a path that is otherwise filled with way more rejection than acceptance. And besides, who doesn’t need more wine and chocolate in their life? Happy celebrating! |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed