|

Writer’s Block is a phrase that seems to come up wherever aspiring writers congregate, whether online or IRL. Either they worry they have it (because words don’t magically flow like water from their fingertips when they sit down to write), or they worry about its inevitable appearance (because although things may be going fine at the moment, apparently it afflicts all writers at one time or another). So here’s a thought: instead of considering it something to fear, consider it something to, well… not exactly look forward to, but listen to. Like heeding a caution sign on a twisty road or taking advice from a wise friend. My operating theory is that what we call “writer’s block” is our subconscious trying to tell us something. And the corollary is that we might benefit from paying attention to it instead of trying to brute-force our way through it. For me at least, the inability to really sink my teeth into a writing project is usually code for “I haven’t thought about it quite enough yet.” I rarely get the long-term feeling of “I’m totally empty and have no idea what to write” (and when I do, it’s almost always the universe telling me to take a break) but more often I’ll get stuck on a specific story issue, whether plot or character-related. I’ve come to believe this is my creative mind trying to tell me—as directly as it can—that I need to cogitate a little more about the story before committing words to paper. I try not to sit down to write until I have at least a vague clue as to where I’m going because—for me—the least productive place to come up with new ideas is sitting on my butt staring at a blank screen. I’d rather mow the lawn or wash the dishes or stand in the shower. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I think the real writing happens away from the keyboard, and I also believe the subconscious does much of the heavy lifting when it comes to creativity. So if I’m stuck on a plot point, I’ll go for a run (or any other activity that takes just a minimal amount of attention). The slight attention requirement of running or walking or whatever seems to distract the conscious mind just enough to let the subconscious come out and play. Then during the run I’ll sort of mull over the scene in question, playing it in my head like a movie. Each time I play the clip I change it a little, and sooner or later an idea will pop into my mind. And if it’s a good idea, I get that “aha!” feeling. If not, I keep playing the film clip until I do. (Or until the lawn is mowed or the run is over, in which case I let it go for the time being.) Then, assuming I have an inspiring little idea that gets me past the sticking point, I’m ready to sit down and begin writing. And of course, once you have enough of an idea to start a scene, your mind generally comes up with other ideas to extend or complete the scene. Another part of the solution to what people call “writer’s block” may be as simple as writing regularly. It’s an over-used phrase but there’s some truth in the simple concept of “ass in chair.” Like most skills, if you exercise it regularly you not only get better at it—in terms of craft—but you also get more efficient at it. And you develop confidence that if you start the tiny little scene you have in mind, you’ll likely come up with more. (I can’t count the times I’ve sat down to write with only a sliver of an idea in mind—thinking I’ll probably run out of creative steam in ten minutes—and I end up going for several pages. The trick is just capturing that initial spark, then putting in the work.) A related aspect of this is simply habit. Some authors advocate writing at the same time and place every day, in an effort to condition your mind to be creative on schedule. This has all the earmarks of a good idea—by all means, give it a try if it fits your workflow. That level of specificity doesn’t work for me, but the overall concept does. I find that if I work on my story in some fashion every day (or for some value of “every day” approximating “most days of the week”) then, everything else being equal, the writing comes easier than when I let it sit for several days on a regular basis. And “working on” doesn’t have to mean original-drafting exclusively. It can mean researching and making notes, or outlining the next few chapters, or maybe going back and editing what I wrote in my last few sessions. (And of course, it can mean simply writing.) The point is, touching base with your book daily—in some fashion—will keep the story in your mind. And this is one of the keys to keeping your subconscious engaged. I also find it helps to have a sense of overall direction. I’m not a detailed outliner, but I like a few signposts along the way, and I like to have at least a rough idea as to how things might end. (A provisional ending, if you will. I might change it when I get there but for now I just want something to drive toward.) Using a road trip as an analogy, I don’t need a detailed route mapped out, with every little meal stop and gas station and motel already decided on… please. But I like broad ideas, on the order of: “I’m starting on the East Coast—let’s say New York—and heading to the West Coast. I think I’ll swing down through the South instead of the Mid-West because I prefer the warmer weather and the BBQ… maybe Atlanta, maybe Birmingham, maybe New Orleans… not sure yet. But I know I want to drive through the Southwest, then on to the coast. Final destination is either L.A. or San Francisco… I’ll know more when I get closer.” That’s pretty much all I need, and I’m ready to go. Enough to keep me moving along, but not so much that I can’t take a detour if it looks promising. We all have different working methodologies and I’m not saying, “Simply do this, and all will be well.” You have to find what works for you. But how you cast things within your own mind can have a big impact on how they affect you, so consider re-casting your perception of what’s commonly called “writer’s block,” maybe to the point of not applying that phrase to yourself in any sort of regular setting. Imagine you’re building a shed in your backyard. You decide on the basic size and shape… maybe you pour a footing. Then before you continue you get some cool ideas about how you want to configure the walls… maybe you want more windows? A friend stops by and says, “What’s wrong? I thought you were building a shed. Why aren’t you pounding nails already?” Would you say, “I don’t know. I think maybe I have…” (poignant pause) “…builder’s block.”? No, you’d say, “I am building a shed. I just need to decide a few more things before I start pounding nails.” So maybe you don’t have writer’s block after all. Maybe you just need to decide a few more things before you start pounding the keys. Which isn’t an excuse for TV and bon-bons—you still need to maintain forward momentum. So if you need to make a few more decisions before you start (or return to) initial drafting, that’s fine. Don’t over-think it. Just stay in touch with your story—and give your subconscious fuel—as regularly as possible, and you’ll get there.

0 Comments

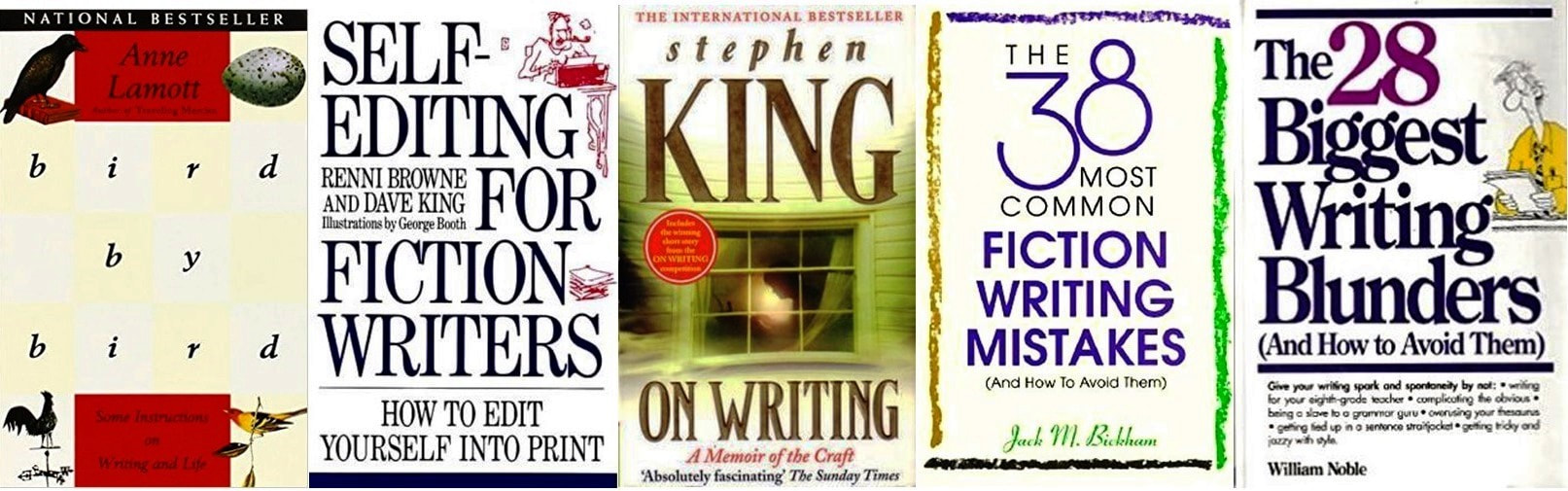

Make us remember you. I read a LOT of newly-published YA fiction this past year, trad-pub’d and indie-pub’d alike. And I really enjoyed most of it. Part of that enjoyment may stem from the fact that I do my best to read as a reader, not a writer. As an author this is difficult, because often you can’t help but see the cogs turning behind the scenes. But sometimes the writing is so effortless that it disappears entirely and you’re left with nothing but story. I love when this happens—when you enjoy the book as a story instead of analyzing the authorial choices the writer made. But things can happen that jerk you out of the story and back into writing-analysis mode. If I had to name the most common place this occurs for me, that would be easy—the ending. Sometimes they feel tacked on, like the book was due so the author just ginned up an ending and sent it off. Or maybe the author had a good idea but sent it off before it was thoroughly revised and polished, closer to a first draft than a finished book. I understand that sometimes authors are under time constraints. And sometimes you’ve spent so much time with a book that you just want to get it over with. But the absolute worst place to phone it in, writing-wise, is the ending. Think about a book you read long ago which made a lasting impression. You probably can’t recall all the specifics, but you probably do recall the feeling it left you with when you closed the cover. And that’s at least partly due to the ending. Looking back, did the ending relate to the rest of the book and support it? Did it have a certain amount of gravity to it? Did it make the theme of the book a little more clear, or a little more important? Did it serve almost as a stand-in for the book itself, in miniature? I’m not saying every book needs to have a ‘Great American Novel’-type ending. But the resolution should at least be at the same level—thematically as well as craft-wise—as the rest of the work. If not, it can do more harm-per-word than a weak passage elsewhere in the book. Why? Because the final lines in any part of a book carry more heft than if the same words were placed in the middle somewhere. Having text followed by white space—at the end of a section, or a chapter, or the entire book—puts a spotlight on it and seems to automatically imbue it with more importance. Maybe because it seems to signal a change… a summation of what’s transpired or a hint of what’s to come. Maybe both. And maybe because there’s a natural pause when you reach the end of a section or chapter or book where you can’t help but hear the line in your head. Echoing. Resonating. These are the top five issues that come to mind, looking back at recent reads with less than satisfying endings: 1. It feels rushed. A book I read recently had a couple involuntarily separated throughout most of the story, over a multi-year span. Their reunion was the scene the entire novel was building toward, but when it finally happened it was sort of hug/kiss/I missed you/I missed you too/The End. If the ending is more denouement than resolution, it doesn’t have to be a major set-piece. But if the ending is the climactic scene, give it its due. You can always trim, if you (or your editor) later decide it’s too much. Think of it like you’re dressing for an important event. Spend some time with it. Try different things on, maybe clothes you don’t normally wear. Hang out in front of the mirror, turning this way and that, until you’re not just vaguely satisfied with it, but really happy. You don’t want to leave the dressing room until you’re feeling like, Damn… I look sharp and I know it! 2. It’s at odds with the rest of the book. Funny can be good. Introspective can be good. So can outright tragedy. But you should have a very good reason to have a melancholy resolution to what’s been a light comedy up until then, or to suddenly have everything all sugary at the end of a dark literary novel. I recall a novel where the author resolved a life-or-death situation with a bad play on words. And I strongly suspect he had this in mind all along and just couldn’t bear let it go, even though it would have been stronger without it. 3. It has characters acting out of character. You can create characters as wild and unique as you like, but to be believable they need to be self-consistent. If you have to have them do something untrue to their nature at the very end to make your plot “work”, you either need to re-think your plot or revise your character. One recent book had an intelligent, funny, self-aware protagonist who was completely rational throughout the entire book, then the big reveal was… he was just batshit crazy and making it all up. Hmm. The ‘unreliable narrator’ technique can work well… if we get subtle clues along the way that their version of events might not be completely truthful. Otherwise it feels like a lazy way out or an unrealistic cheat. Likewise the very passive girl who suddenly developed an extreme case of agency while her friend—who’d been driving events all the way through the book—suddenly turned into a pull toy and let herself be dragged through the climactic scenes. I can buy flying monkeys, but not that. 4. It doesn’t hold up its end of the bargain. With most fiction (and more so with genre fiction) there is an implicit deal between author and reader. With a romance, someone is going to get together with someone else. Maybe not the someone you had in mind, but someone. Eventually. And we should care about it. Same with mysteries. There is a crime, there is a solution, and we should care. Don’t lose sight of why the reader is there. I recently read a mystery which was well written at first… until the story got so lost in following the victims during the aftermath that the ending fizzled. Any crime solving—such as there was—was done off-stage by police, not the main characters. Basically the denouement was: “An old mad-scientist was the culprit but he’s gone now so who cares anyway?” Good question. Not me. 5. It doesn’t resonate. This might be trickier to diagnose and fix, but if your ending seems to fall flat, look to see if it ties back to the rest of the story, if it addresses what your protagonist was looking for earlier in the story, or if it reinforces the theme of the story. If it doesn’t seem to do any of these, it may not carry the resonance that helps create a satisfying ending. Not to get too lit-geeky here, but the word “resonance” technically means one object or system vibrating in sympathy with another, usually caused by one exciting the natural frequency of the other. The ending of the final chapter of a novel is not (or should not be) the same as the ending of a random chapter somewhere in the middle. It’s not just about summing up recent plot points or hinting at what’s happening next. It should somehow tie back to earlier events and put them in some sort of perspective or provide resolution or summation, but ideally without actually telling us this is what it’s doing. Understatement, metaphor, and oblique reference can be wonderful here. I think it’s important to remember that a strong, resonant ending (as defined by you, the author) doesn’t always come from the first thing that pops into your brain. This is an area where it can pay to spend some time, revisiting the ending during initial drafting and then again during revisions until you’re truly happy with it. It’s called a resolution for a reason. So don’t leave the ending until—like the final notes of a song that fully resolves the chord pattern—it feels truly complete. Make us remember you. There’s been a lot of discussion lately about authenticity in literature (or the lack thereof). I like to believe most of the failures in this area aren’t someone intentionally trying to demean, dismiss, or disrespect the culture of another. I think many of these are simply the writer being unaware of the amount of work it requires to authentically represent a different culture or subculture, or perhaps being unwilling or unable to put in the necessary hours to bring the work up from “stereotype” to “accurate representation.” Authenticity in fiction requires respect, research, and empathy. And craft, which is sometimes overlooked in these discussions. The first decision an author has to make—before a single word is drafted—is to decide whether or not they should even write the story. Let’s imagine someone suggests that a good character and setting for a realistic contemporary novel might be the story of a Japanese teen-age lesbian, struggling to make it through high school in modern-day Kyoto. It wouldn’t take me long to arrive at the conclusion that maybe I should pass on this one… I was raised in the States, have never been to Kyoto let alone absorbed the culture, and have scant knowledge of the LGBT culture among Japanese youth (which may very well vary between big cities and smaller towns). There are many ways I could get it wrong, and the cost to insure I didn’t would be too high. This isn’t to imply that a writer with my general background couldn’t do it, but the effort needed to get up to speed and do it authentically would be very substantial. Of course, all cases aren’t this blatant. There is a subculture with which I am intimately familiar: that of the working musician, playing in clubs both locally and on the road. So when I wrote Road Rash—although I was deeply concerned with things like voice, character, plotting, theme, dialog, and the overall vibe of the story—the one thing I didn’t have to sweat too much was the verisimilitude of the background, because BT/DT. But what if you want to write about something you haven’t been steeped in for years? Does this mean you can’t do it? Not necessarily. Let’s compare and contrast two approaches taken in recent realistic/contemporary novels… both featuring fairly similar band-on-the-road settings, and both written by non-musicians: In the first one, the author basically took the "plug & play" approach: they sat back and thought, “Hmm…I wonder what it’s like to be in a band on tour, playing smaller venues?”, then wrote the story based on what they assumed it might be like, with zero research. How do I know? Because the book is so full of large, almost-comical errors that any musician who’d vetted the book would have pointed out the howlers immediately. I realize everyone’s experience is not my own, but there are basic facts of road life that are universal. (Just one of many: a band on tour—hauling their own equipment, including sound system—does not pull up at a new venue, waltz inside and get a drink, and then begin playing within five minutes. Trust me.) I could go on, but you get the idea. I finished the book and thought, Wow—they didn’t bother to ask a single question or do any research to even try to get it remotely right. This is a traditionally-published author, by the way, who lives in a city with a vibrant music scene. So basic fact-checking would have been easy-peasy. [*An interesting side note is that none of the book’s reviews—which were mixed but overall fairly favorable—mentioned this. Which goes to show that just because a book seems fine to a mainstream audience doesn’t mean it’s not problematic to other sectors of the reading public.] With the second book, the author (well published, with a long and successful writing career) realized their next book was going to contain settings that were new to them (a couple of the main characters were in a touring band) so they did their research. Realizing they still had some gaps in their knowledge base, they contacted another author they’d met on book tour who they knew was a musician (yours truly, but it could just as well have been the bass player at the local bar). They asked a number of questions regarding life as a working musician, including queries about logistics, finances, band politics, etc. Then they laid out the part of the plot that revolved around band life and basically said, Does this make sense? Does this feel authentic, from a musician standpoint? I’m happy to report that yes, the finished book felt completely authentic, and I was never pulled out of the story because something unbelievable happened. All because the author took the time to do some vetting and fundamental fact-checking. Granted, sometimes it’s a bit more difficult than asking a few question of an informed source. Sometimes you need to roll up your sleeves and get seriously involved to really get at the emotional heart of a story. I can think of no better example than The Running Dream, by Wendelin Van Draanen—a YA novel about a teenage girl who loses a leg in an accident. There were two years of solid research behind this book before a word was written. First was the decision to even write the book at all. She fought against the urge to write it for quite a while because she knew it would involve a ton of work to do it right, but the story (conceived on our flight home after running the New York marathon, where we’d seen people with severe challenges struggle to run 26.2 miles) just wouldn’t let her go. Once she decided to tackle it, she started where you might expect—she read several books about amputation, prostheses, and recovery. It’s important to note that this was not to write the book itself (which is a common mistake writers make) but simply to give her the technical background so she’d be able to ask the right questions of doctors, prosthetists, and amputees. Once she understood the mechanics of the process, then the real work began—getting to the emotional truth of what it’s like to go through such a life-altering event, and then the long adaptation process afterward, leading—in most cases—to finding a new normal, emotionally as well as physically. She interviewed people who make prostheses. She interviewed people who fit and install them. She interviewed a medical technician who used to be a dancer before she lost her leg, and can now move quite well on her prosthesis. She interviewed doctors. And of course she interviewed amputees. Lots of amputees. Which takes a slow and thoughtful approach—you can’t just walk up to someone and ask them to please take off their leg for you. But the opposite happened. One patient who was visiting his prosthetist for a re-fit and a “tune-up” answered Wendelin’s questions, then asked, “Do you want to see how this all works?” He allowed Wendelin to watch (and photograph) the prosthesis removal and re-installation process, and then talked about the entire ordeal he’d been through since losing his leg. After the book came out, a woman who was a medal-winning Paralympic athlete (below-knee amputee runner, just like the protagonist in Wendelin’s book) read The Running Dream, loved it, and used it in her own educational visits to schools around the country. When she learned through a mutual acquaintance that Wendelin had two organic legs, she expressed her surprise. “When I first read the book,” she said, “I thought for sure that the author must be an amputee, because she got everything so right… not just the medical stuff, but the way it feels… the way you feel when you wear a prosthesis every day.” I’d guess I’d call this the definition of “getting it right.” On the opposite end of the spectrum, I just finished reading a book featuring a protagonist who has a neurological condition with which I’m familiar. The author got it so effing wrong—in seriously fundamental ways—that it seemed like she’d simply gone down a list, looking for a condition she could plaster across her character’s forehead as a device to differentiate her from other teen protagonists. And once she found something she thought sounded interesting, she stopped long enough to read a single paragraph (at most) on Wikipedia, then invented a bunch of wildly inaccurate stuff and ran with it. (And this book was traditionally published, which begs the related question of where was the editor?) So yes, it is possible for an author to write authentically about a group other than their own—females can write male characters, middle-aged adults can write child characters or senior characters, authors can write characters outside their religion, race, or gender identity. But only if they treat their characters with enough respect to do the hard work necessary to get it right. And there’s a bonus to getting it right… One of the very best things about being a writer is all the interesting stuff you learn when you take a deep dive into something new, and a big part of authenticity in writing involves exactly that—research, interviews, study, and other forms of self-education... up to and including gathering hands-on experience. And in the process your writing becomes more accurate, your characters more three-dimensional, your setting more believable, your plotting more realistic… and you get a bit more educated in the bargain. What’s not to love about that? Writing can be a solitary gig, but it doesn’t have to be. I’m not talking about joining a writers group or taking a writing class. I’m talking about seeking help from people who’ve done what you’re trying to do. AND lived to tell the tale. (In written form, of course.) There are hundreds (thousands?) of books available on some aspect of writing. We have a bookcase containing at least fifty of them sitting three feet from where I write this. Some are strictly craft, some are rules of the road, some are reference, some are about publishing, and some are about the sometimes-elusive writing mindset. And I suppose all of them have been useful to someone, somewhere, at some time. But—for my money—the ones that are the most useful are the ones that inspire you, that make you feel you’re not alone, that give you a creative flashlight to shine in the darkness. In other words, the ones that make you want to write. Because in the end, you’re not going to succeed at something you don’t want to do. The following are suggestions for resources that raise the odds you’ll put in the work necessary to get where you want to go. (And yes, a strictly nuts-and-bolts craft book can be as inspiring as a writerly memoir if it’s done in a way that helps you focus and makes you want to sit down and tackle those tough revision issues…) “Bird by Bird,” by Anne Lamott. This is a wonderful little book, almost magical in the way it gives writers permission to write without worrying about perfection. The admonishment to “Give yourself permission to write a shitty first draft” is enough of a take-away in itself to make it worth the cover price. (I’ve given away three or four copies of this book to aspiring writers.) She covers important topics about writing (and the writing life) in such a kind, wise, generous, and humorous manner that it’s more like a heartfelt discussion with a good friend than a text on writing. “Self-Editing for Fiction Writers,” by Renni Brown and Dave King (with occasional—and hilarious—illustrations by Goerge Booth, of The New Yorker fame). In some ways—even though ostensibly a craft book—this goes hand-in-hand with the two more memoir-ish books in the group. One of the most important things for an aspiring writer to grasp is that they’ll never even get their book in front of an editor until they learn to edit their own work. Which is very different than writing. Assuming traditional publication, you won’t be the only editor on your book, but you’ll almost certainly be the first. (And in a sense, the most important, because once you get a “yes” from a publisher, the rest is simply hard work. But getting that initial yes depends quite a bit on your revision abilities.) “On Writing,” by Stephen King (subtitled “A Memoir of the Craft,” which is a great description as it’s as much memoir as writing how-to). I love this book because it gives you a peek into the “writer mindset” better than perhaps any other volume. His advice on writing (specifically self-editing) is spot on, and he speaks directly to the issue without a lot of theoretical pontificating. I’m not a huge fan of the “Here’s the formula to writing your novel!”-type books, and King’s book is the antithesis of this. He’s an instinctive writer, and his idea of plotting is basically to just start writing and let the story out. Even if you’re more of a plotter than a pantser, it can be freeing to know that some of the most beloved (and successful) novels of the 20th/21st Century were written with no outline whatsoever, let alone following a detailed formula involving prescriptions like “have the inciting incident occur within the first 15% of the manuscript.” And beyond all that, it’s simply a great read (as you might expect from Mr. King). “The 38 Most Common Fiction Writing Mistakes” (Jack Bickham) and “The 28 Biggest Writing Blunders” (William Noble). These two concise volumes make nice bookends (together they’re less than 250 pages). We’re treating them singly because they’re like two books you might read for the same writing class… one at the beginning of the semester and the other near the end. Both were published by Writer’s Digest Books and both follow the same layout and overall style, down to the (And How to Avoid Them) subtitle after their proper titles. “38 Common Mistakes” is great for beginning fiction writers. I don’t necessarily agree with everything the author says, but overall it’s very solid advice for aspiring writers, under the “you have to know the rules before breaking them” adage. (Ex: “Don’t be constantly bouncing around between POVs.” Sure, this can—and is—broken frequently, and sometimes successfully, but it’s helpful advice for someone seeking clarity in writing their first novel.) “28 Biggest Blunders,” on the other hand, is a better fit for someone with a half-million words under their belt, focusing on more esoteric topics like voice and style instead of primarily nuts-and-bolts like grammar and technique. One thing I really like about both is if you have questions about a specific writing topic, just glancing down the (very descriptive) table of contents in either volume will likely lead you directly to an answer… or at least point you in the right direction. There are obviously many more helpful books on writing (to say nothing of some of the great writing-related sites online, which we should discuss later), but if you ever feel the need for a shot of writing inspiration—or maybe some well-thought-out ideas about the craft of putting a story together—you could do worse than to start with these. The bottom line is that you don’t have to do it alone. There’s plenty of advice, inspiration, and technical know-how available, as close as your nearest bookstore, library, or web browser. Are there any favorite writing books that inspire you to sit down and pound the keys? If so, tell us in the comments! |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed