|

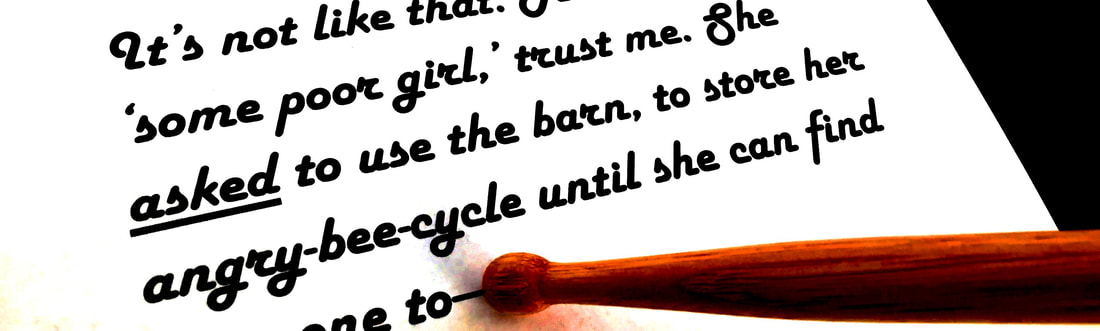

In talking with young musicians, one teachable point seems to come up repeatedly—the benefits of being about to “get outside yourself.” Working on an art form isn’t always a smooth learning curve. There are definite peaks, with plateaus - and even valleys - in between. With music, one of the leveling-up accomplishments is being able to get outside yourself as a creator. Typically, we learn how to play our chosen instrument somewhat, then we start a band. With many young bands, you watch them play and realize they’re a bunch of musicians playing in the same room at the same time, but they’re not really a band yet. You can tell they’re each thinking only about what they’re doing as they’re doing it (the epitome of this is looking at your hands as you play, with no regard for what anyone else is doing). Then, as the next step, they start to think about what they’re going to play, with little concern for how it’s going to fit into the song. (The example here is the young drummer who’s determined to play that flashy fill he just learned—no matter what—even though it doesn’t fit the mood of the music. Ask me how I know…) A big leap forward is finally getting to a place where you aren’t thinking about your own playing in the moment at all; you’re listening to the music as a whole and adjusting to the others, trying to make it sound like a cohesive unit. Then, ultimately, you want to be able to interact with the band almost without conscious thought and really get some distance from it, so you can step back and hear the music as it appears to the audience. Because—unless you’re just playing by yourself for the fun of it—one of the primary goals is to have the audience feel what you’re attempting to convey. It doesn’t really help if you’re working away but your creative ideas aren’t coming through due to a disconnect between intention and execution. It’s the same with writing—it really helps to be able to step back and look at it from the outside. You know what you want to say with your story, but is it getting across to the readers? Imagine you’ve designed a cool piece of office furniture, with the goal being that other people might buy and assemble it so they, too, can enjoy it. If the overall design is good but the instructions aren’t clear and concise, it’s going to be a frustrating experience for the customer. I think this is a not-uncommon weak spot for many of us: we have a good story idea, but our implementation may lack the perspective to get our story across to the reader the way we intend. I saw a manuscript recently containing something like: He hung his head. “I did a poor job,” he said dejectedly. I’ve done this myself. It comes from us (as writers) being really intent on making sure the reader knows exactly how the character feels. So we overdo it and veer into territory that we (as readers) might find less-than-transparent while reading. (When you read a line like this, you can almost see the writer looking at his hands as he plays.) But if we get outside of our good writing intentions and view it from the other side, we can see that simplifying it might make the writing itself less intrusive on the story. Looking at the above snippet as a reader, if the description of the character’s mood is clear enough through his actions (i.e. showing) we don’t need the “dejectedly” (i.e. telling). So, He hung his head. “I did a poor job,” he said. reads smoother and is less clunky. (“ly” adverbs used as dialog descriptors are often clunky sounding to readers, and our inclination to use one should be taken as a sign that we may need to show more of the character’s mood vs. telling the reader about it.) And since the author is already talking about “him,” the reader doesn’t need an attribution at all. So, He hung his head. “I did a poor job.” is even tighter and smoother, and every bit as clear. (And as I’ve heard from my editor more than once, tighter is usually better. Especially from the reader’s point of view.) I’m as guilty as anyone of creating this sort of prose during initial draft. One way to mitigate it is to write it, then take off the writing hat and put on the editing hat while you do what you can to make sure everything’s consistent, tight, believable, engaging, etc. Then go yet a step further in getting outside yourself—take off the editing hat and put on the reader’s hat. While letting some time pass in the interim, if possible. And while you read, try to stay in the mindset of: I’m a new reader to this work… I didn’t write it, I didn’t edit it, and I have no idea where it’s going. I’m simply going along for the ride. Then, as you read, try to stay attuned to your enjoyment level. If it wanes, look for and note any nearby plot drift or inconsistent characterization or over-explained motivation—even down to the sentence level as in our example above. Then, when you’ve finished reading it, you can put your writing hat back on and revise to those notes, then back to the editing hat, and so on. Writing is interactive, but not just between author and editor. It’s also between writer and reader. But before you get to a real editor—or to real readers—you may have to assume both roles along the way. So don’t look at your hands as you play, don’t place cleverness above clarity, and don’t try to shoehorn that brilliant riff you just thought of into chapter two if it doesn’t fit. And most important, occasionally get outside yourself and listen from a distance to make sure your ideas are getting across as intended and your audience is along for the ride.

0 Comments

|

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed