|

Ask any fiction writer what the most common question they get is and you’ll likely hear: “Where* do you get your ideas**?” [*Taking the question literally, the plausible answers are either (1) inside my head (i.e. from my imagination), (2) outside my head (i.e. from the world around me), or (3) a combination of 1 & 2 (i.e. take some event from some place and sometime in the world and re-imagine it into something else). #3 is—by far—the most common.] [**FYI, writers speak of this question amongst themselves the way musicians talk about requests to play Mustang Sally or Free Bird. Just sayin…] But the question behind the question is likely something more along the lines of: How do you develop the seed of an idea into a story? This question is actually interesting—to writers as well as readers—because while the former has three answers (inside/outside/both), the latter has as many answers as there are writers. So I’m not suggesting that what works for one writer will absolutely work for another. We’re all different. But if nothing else, looking at someone else’s process can help jumpstart your own, different though it may be. It might sound funny, but spinning a bedtime story completely on the fly—no notes, no pre-plotting, no outline—might be one of the best storytelling lessons we can have, for a few different reasons. When our boys were little we would read them bedtime stories, pretty much from birth. Somewhere in there—they were maybe two and four—I opted to tell them a story instead of reading them one. (Extemporize, not re-tell a classic.) For some reason—probably because I could be as wild and goofy and stupid about it as I wanted—they enjoyed it. So I got roped into doing it on the regular. Not every night, but perhaps three or four times a week. Maybe someone else could world-build a totally unique setting and character-set every night (after an 8-to-12 hr. workday) but not me... I quickly learned the best way for me was to have several serialized stories going at once, in episodic fashion, and let them pick one each night and spin a little bit more of it. No plotting or outlining allowed, because you didn’t even know which one it was going to be until you were lying on the floor with the lights out and a little voice would say, “Could we hear Cousin Crow, Dad?” And you’d say, “Really? Are you sure? I don’t think so…” And they’d start yelling, “Cousin Crow!!! Cousin Crow!!! Cousin Crow!!!” and you’d be off to the races, talking about whatever trouble that crazy bird was getting into next… This went on for six or seven years. A couple hundred stories a year. Easily a thousand or so by the time we moved on to “Novels at Night.” Stories where the goal was to entertain them and make them laugh, and maybe even make them think about things in a new way. These stories certainly weren’t War and Peace, believe me. Mostly goofy stories about various people and creatures having adventures and getting into trouble*. [*Ex: There was a young dude who worked in a science lab—I named him “Wilbur the Science Guy” in a fit of stunning creativity—who was smart but absent-minded. He really liked to eat but he really didn’t like to waste time so he hot-rodded the lab’s microwave oven so it would cook a frozen burrito in two seconds instead of two minutes, which was awesome right up until he forgot and put in a burrito and set it for two minutes. The massive over-nuking of the burrito resulted not only in an explosion that plastered the lab’s walls with stinky, slimy beans and cheese, but also created a time warp that sent Wilbur back to medieval days, where further adventures featured him trying to explain science to a stupid and pompous king who didn’t believe in science. This was twenty years ago, btw…] So, a few benefits of this ad hoc storytelling process… 1. It encourages us to exercise our “going with our gut” story development muscles. (AKA “organic” writing.) Because there’s no time for over-thinking. The main driver is simply, “What interesting thing could happen right now?” and then riffing on that. 2. You get instant feedback from your “readers.” If a couple of monkey boys are bored by your story, you’ll hear about it. Instantly. And loudly. (OTOH, if they find something funny, you’ll know that right away, too.) 3. You tend to consider—and play to—your audience. Not that this should always be the top priority when wordsmithing, but when writing for a specific age group—whether picture book, chapter book, middle grade, or YA—it’s certainly helpful to know who’s reading, and what they may likely be interested in. (Bottom line—if you don’t interest your readers, they won’t want to read your book. It's that simple, but sometimes we forget.) 4. You learn to create—and abandon—ideas quickly. Like, at the speed of speech if not faster. If something isn’t working, you quickly pivot and try something else. Sometimes you’ll think of an idea and toss it before it even comes out of your mouth. This translates well to doing actual plotting on, like, an actual book. Again, none of these stories were the Great American Novel. Not by a longshot. But they taught me some valuable lessons. Lessons I still use today. Lessons we could use tomorrow. Because after all, isn’t the ultimate goal the same—to keep the reader tuned in and engaged in your story, no matter what? Happy spinning!

0 Comments

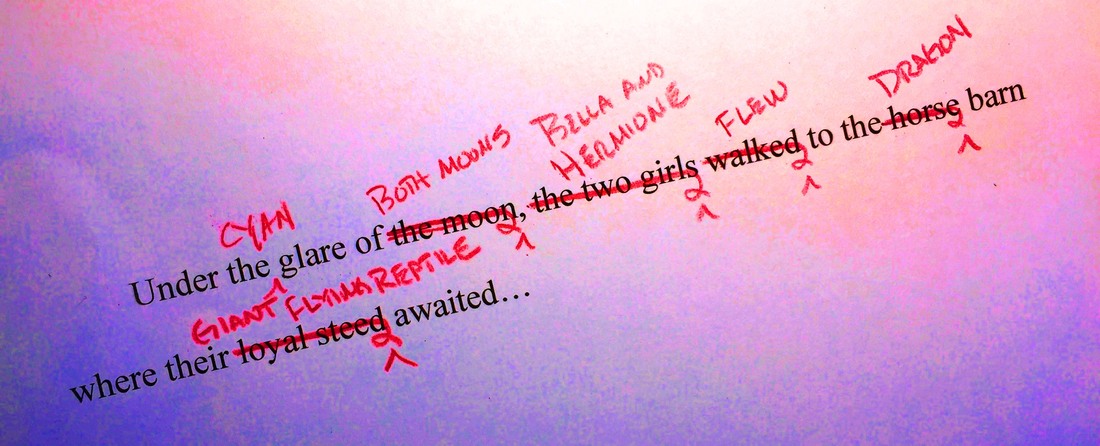

I was doing a workshop for young writers recently and as usual I started with a quick assessment… Who writes—or wants to write—the following: …Short stories? …Articles? …Essays? …Blog posts? …Graphic novels? …Journalism? …Nonfiction books? …Novels? And so on… The good news is I saw several hands go up for each area, and many of them went up multiple times. Then on a whim I added, …and what about fanfic? Lots of hands, and (even more important) lots of excitement. “Awesome!” I said, and we were off and running. Fast-forward to a while later, as we’re discussing the revision process. I’m trying to give them two fundamental takeaways… 1. Revision can really improve our work. 2. Revision can really be enjoyable. (Because without them buying into #2, #1 isn’t likely to happen.) The first one is pretty direct: Revision is where you can go from good to great, etc., along with explaining various reasons why virtually any manuscript can be made better with judicious revision. The teachers are nodding in agreement, and the students seem to get the idea. In theory. The second one is a harder sell. I talk about how I changed my mindset from dreading revision to enjoying it. “Look at it this way: you’ve actually reached the end, and in the big picture it probably hangs together as a story to one degree or another. So the stress of wondering if you’re even going to finish the initial draft is gone. You made it! Now you get to return to your world and make it even better and—” I stopped, as something struck me. “Remind me again—who’s into fan fiction?” Three fourths of the students put their hands up. “Well, this is similar.” I had their attention now, if not their concurrence. “With fanfic, you start with a world you love and characters you love and a basic story holding it all together, right?” They nodded. “So you don’t have to do the heavy lifting of world-building or character creation or fundamental rulemaking because it’s already been taken care of, right?” More nods. “So, you guys are basically saying that the fun of it is, you get to dive back into that world and improve things and add new things and just generally make it into the story you always thought it should be. Sound familiar?” The room lit up with fifty or so lightbulbs turning on. Including the one above my head. It was my turn to nod. “So it sounds like… revision is doing fan fiction on your own story!” And it is. My views on revision changed when I began to realize it was an opportunity to go back to the world I’d created—and the characters I’d created and was invested in—and play around some more. (With credit to my child bride here, because she got over her dislike of rewriting before I did and thus helped show me there was light at the end of the tunnel.) And I think a big part of this is—as we’ve discussed before—reading like a reader instead of a writer: Take some time away from the story then go through it like a fan. And as you read, keep note of the things that bore you or confuse you or that you’d just like to see done better or different. Then take that punch list and go back through it as “writer you” and make all the changes that “reader you” was wishing for, making sure the transitions are smooth and natural and that none of the stitches are visible after the surgery. And when you’re done… congratulations! You’ve just created some awesome fanfic based on the work of an author near and dear to you. Happy Revising! …so five minutes ago—as I write this—one of the best writers I know is working toward the end of perhaps the best thing she’s ever written, and tears are pouring down her face. She notices me in the room and looks up from her laptop, eyes wide. I don’t even have to ask. “Oh, my poor little friends!” she says by way of explanation, then blinks as more tears run down her face. And—because I know her little friends too—I nod, and suddenly find myself involuntarily joining in. I can think of no better illustration of honest-to-God writer engagement. And I believe pretty firmly that without writer engagement—real, gut-level, emotional involvement with your characters—it’s very hard to generate that level of reader engagement. In other words, you have to give a shit. And how do we do that? A good start might be to internalize the concept that caring is an emotion, not a thought. The good news is we all have a built-in barometer for things like this. We don’t have to think about it—in fact, thinking about it puts us at one more degree of remove from it. An analogy might be our sense of taste. When we take a bite of something—for example, homemade hand-cranked vanilla ice cream—most of us can answer the question, “Do you like it?” without too much intellectualizing, especially if we just listen to our initial emotional response and don’t think things like, ‘Is this healthy?’ or ‘Is this considered quality food?’ or ‘Do other people like it?’ The same can apply to your characters. Instead of thinking (there’s that word again), ‘My character has been designed with these attributes and those personality traits and faces this specific challenge—which the reader should be able to relate to,’ maybe ask yourself the simple question, ‘Do I care about them?’ Go with your gut response here rather than an intellectual one. [NOTE: This doesn’t necessarily mean you have to like them, although it can certainly help you—and readers—care about them and what happens to them. There’s a time-honored place in literature for the unlikeable protagonist, although this only seems to really work when the author sets out from page one to purposely create a fascinating-yet-unlikeable protagonist. I think the fairly common criticism of a book “having an unlikeable main character” usually means the author unintentionally created a not-very-likeable character. This is a subject deserving of its own post, but one thing that can definitely help here is the use of good betas.] [NOTE #2: We should also recognize there are plenty of novels where having an emotional connection with the main character isn’t a top priority, either for the author or the reader. These could be plot-driven thrillers or humorous capers or broad historicals or any number of other types. And these can certainly be entertaining, successful works, but they’re typically not as likely to be the sort of stories readers bond with for the long haul… the type that sometimes come to be known as “beloved.” Maybe because humans seem to be hardwired to be more invested when there’s a person in the story they truly care about.] So how can we raise the odds of this connection happening? I think it’s largely a matter of spending time with them. I have a theory that, everything else being equal, the more time we spend with someone—assuming they’re generally good people—the more they come to mean to us. (I think this may be anthropologically tied to the human concept of “family.”) Regardless, by “spending time” I don’t necessarily mean writing a thousand page book about them. I mean letting them occupy space in your head… and in your heart. When possible, spend some non-writing time thinking about them, just running scenarios through your head and imagining what they might do in various situations. Yes, this’ll also help you come up with plot ideas, but maybe even more important, it’ll help you get to know about them—and care about them—as individuals. And if we invest enough time, attention, and research into our characters, they can become real to us. Not real in a “break with reality and visit the psych ward” sense. Real in an emotional sense. In the same sense that we—as readers—might care about Harry & Hermione & Ron or Hazel Grace & Augustus or Liesel & Rudy or whichever characters you’ve ever found yourself personally invested in. And if you develop an emotional attachment to your characters to the extent that you find yourself springing a leak over your ‘little friends,’ take it as a sign that your readers might feel the same way. Which—when you boil it all down—is the whole point of what we’re trying to do here, right? Happy crying! |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed