|

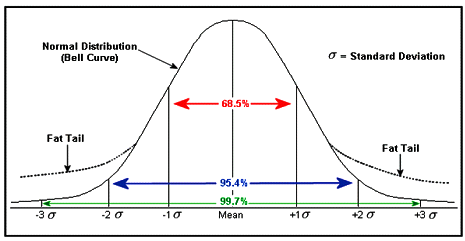

Last time we discussed counting words, and whether it helps or hinders or has no real effect at all. (Short answer: All of the above. Depending on you, your project, and your goals. And, of course, the KUWTJ factor*. But under no circumstances is it unconditionally required.) (*Keeping Up With The Joneses.) And as I mentioned, there doesn’t seem to be any obvious correlation between counting and quality, either way. But there is a related factor that actually does seem to affect quality. And that’s pace. In endurance running, there are two ways to screw up a marathon. (Well, there are actually about two million, but we’re only looking at two here.) One is to try and run faster than your optimum pace. And the other is to run well below it. Both will leave you feeling not-so-good, in different ways. And—interestingly enough—both will almost certainly result in a longer finish time than if you’d just found your sweet spot and maintained it. And both result from the same thing: fear. Fear of not keeping up with someone else (or maybe with someone else’s perception of you) which leads to exceeding your optimum pace and blowing up before the finish line. or… Fear that maybe you can’t really do what you actually can (aka fear of failure) which leads to self-doubt and dropping back to “protect yourself.” Guess what? Both of these can apply to writing, too. With this in mind, there are some fundamental concepts regarding pace that might be useful for writers to consider, especially with book-length projects: 1. Your pace is your pace, and no one else’s. It’s not a race (even if others think it is). When you let your pace be dictated by someone else, you’re playing their game. Your goal isn’t to “beat” anyone. It’s to do the best job you can while writing, and feel good about the result after you’re done. (In other words, pace affects both process and result, so no matter which is more important to you, it matters.) 2. Know your pace. This doesn’t come from adopting someone else’s pace or from reading about it on the internet or from what an instructor thinks it should be. This comes from experience. Real, practical, empirical experience. But maybe you haven’t written a novel yet? That’s okay. After you’ve written a bit of it (say 10,000 words or maybe three or four chapters), you’ll have a pretty good idea of what works for you if you’re paying attention. 3. Try to maintain your average pace, within reason. What you’re really looking for is the macro of overall time (as measured in months or years, which we’ll talk about in a minute) as opposed to the micro of words-per-day. And keep in mind: faster is not necessarily better. Better is better. 4. But be flexible about it. Pace is a tool, nothing more. And it’s your friend, not your master. Some days, writing just may not be in the cards for you. Or maybe some weeks, or some months. I’m not talking about making excuses for why you haven’t touched base with your story in forever. I’m talking about those times when life legitimately intrudes, and you either can’t write, or writing might not be the best use of your time at the moment. Don’t beat yourself up—we’re humans, not machines. And even your favorite authors have times when writing is the last thing on their mind. My overall hypothesis about the macro of writing pace for book-length projects: Each of us has an “optimum overall writing time” for the completion of a novel. (This can apply to any big project, but we’re going with novel as the desired outcome here for simplicity’s sake.) And this time can and will vary—greatly—between different writers. And this time can also vary between different types of projects. And this time is not a specific value, but a range—a broad range. And it’s actually more important to know the dangers of being too fast or too slow than knowing your exact optimum writing time. As follows… Too fast: Ideas are like seeds. They can grow into wonderful plants or trees. But before they grow, they have to germinate. And occasionally we’ll get an idea we’re excited about, and without really playing it out in our minds and considering different iterations, we just jump right in and start writing. (I’m guilty here, too… I’m about 60/40 pantser, which doesn’t excuse a lack of basic pondering before committing words to paper.) This can result in one of the more painful aspects of writing: going back to the beginning and starting over. Or—almost as painful—a major structural rewrite. Either way… ouch. Also, sometimes when a writer has an idea and a basic outline and then just cranks the book out, there can be a lack of interesting subplots or three-dimensional characters or maybe just the subtle literary subtext that can give a work more depth. And more often than not, this seems to occur when the author is pushing for speed and maybe writing faster than usual, whether due to internal pressure or external deadline. Too slow: When talking to writers groups, questions about writing schedule invariably come up. And my usual response is, “Everyone is different, with different lives and different priorities. I think you should determine what works best for you and do that.” Because I’m the last person to tell someone else exactly what they should do. The writers - online or at conferences - who stand up and pontificate things like [insert deep announcer voice], “You need to write for an hour every day before work,” are basically talking to themselves. However, I’ll sometimes add, “My only recommendation is that I think it can be helpful to write regularly… for whatever value of regular works for you.” This has nothing to do with the speed at which you crank out words, but everything to do with keeping your subconscious engaged. I’ve said before I think it’s pretty clear the subconscious does a lot of the creative heavy lifting when it comes to story creation. (Which is why it’s almost universal for writers to get ideas while showering or running or driving or washing the dishes or some low-concentration activity that distracts us just enough to let the subconscious come out and play.) But for this to happen, that part of our brain needs to be engaged on a regular basis so it continues to “work” on the problem even when we’re not consciously thinking about it (similar to thinking about a problem before going to sleep and having a solution upon waking). And the way you feed your “creative problem-solving mechanism” (i.e. your subconscious) is to connect with your story regularly. Ideally this involves actually writing on it. But even if you can’t write, then editing or plotting or just re-reading the last few chapters will keep the story in your head and encourage your subconscious to keep working on it behind the scenes. This really seems to increase the odds that next time you sit down to write, you’ll have something worth writing about. This is harder to accomplish if you only touch base with your story once a month or whatever. For me, whenever there’s been a long gap between writing sessions I have to spend quite a bit of time just getting the vibe of the story back in my head. (This seems especially true when it comes to getting the voice right.) So besides basic production issues, there seem to be some real creative benefits to working on your story regularly. The Sweet Spot: If you graphed my writing with “Overall Writing Time” on the X axis and “Subjective Quality” on the Y axis, the result would look pretty much like a standard bell curve. The curve would first start to sweep up at around the six month mark and taper back down near the eighteen month mark, with the sweet spot for overall writing time (everything from initial conception to plotting to writing to revising to polishing to final copy edits) hovering around the twelve month mark. The actual values are meaningless for anyone but me (and you’re missing everything I’ve ever said if you think you should somehow try and approximate them) but the concept remains: Our creative minds seem to have a natural cruising speed they like to function at… thinking and digesting and regurgitating and writing and thinking some more and writing some more then re-thinking and subsequently rewriting, etc. We can certainly work faster than our natural pace (just ask anyone who’s ever had a demanding supervisor) but the results are rarely optimum. And it’s all too easy to work slower (just ask, well… anyone) but here, too, you’re probably not thrilled with the final result, let alone the lowered productivity. Your sweet spot may be six weeks or six months or six years. (And it may vary with your experience level and mood.) The specifics aren’t important. What is important is to be aware of it and—as much as possible—honor it. But don’t over-think it. After all, the goals are pretty simple: 1. Get to the finish line. 2. Be happy with the result.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed