|

Back when we were kids we used to watch reruns of Gumby on TV. I vaguely remember my brother being a fan of the troublemaking Blockheads and I seem to recall my sister liking the concept of being able to walk into books, but being the simple boy I was, my favorite was Gumby’s dog, Nopey. Who could only say one word: “Nope!” (I mean, what willful child wouldn’t identify with a cute, friendly dog that went around saying “Nope!” to everything???) Fast forward a few decades… When we were designing our house, a very smart man looked at our plans, said some complimentary things, then added, “You know, if you angle this wall here, it’ll improve your view over there.” He was right, but I’ll admit that my first response was to channel Nopey because we were in the mindset of “doing it ourselves,” literally starting from a sketch done on a napkin. So I rationalized my reluctance, thinking things like, but then we’ll lose a few square feet in the corner of the room. But the idea was an undeniable improvement—brilliant, actually—and it wasn’t long before we made the change. And virtually every morning since—especially those rare and wonderful mornings when we both have the time to just sit in bed and write—I’ve looked at the view from where we sit and been so thankful we took the suggestion. If you have an editor working on your book—whether paying you or getting paid by you—you don’t have to take all their suggestions. (If you do, there’s probably something wrong.) But if you say “Nope!” to all of them, there’s also probably something wrong. (Namely, you’re not really looking for an editor, you’re looking for a copyeditor. Or more likely a proofreader, as even a copyeditor will have editorial suggestions regarding voice consistency and story continuity and fundamental fact-checking, etc. Whereas when most people refer to a proof reader, they’re thinking of someone acting as a human F7, just checking the basic mechanics of spelling, grammar, and punctuation.) Why do I bring this up? Allow me to spin an apocryphal tale… There was a man who wrote a book. And his book had some really unique and interesting ideas. And when he finished, someone suggested he should have someone with editorial skills take a look at it before he went further. So he went looking for an editor, only he had the above mindset—that editing was scraping a document for mechanical errors. (As we’ve discussed before, thinking an editor does this is akin to thinking a financial advisor simply counts your money for you.) He found his “editor,” a smart young guy who read widely, had a language arts background, and was good at putting his thoughts to paper. And he had the guy read the manuscript, with the instructions that he wanted someone to edit the story, looking for mistakes, etc. And the guy did this, finding the usual typos and wordos, etc. But the guy also had questions, suggestions, and comments. As editors do. Like, “You’ve already explored this argument earlier. Maybe consolidate?” or “I’m unclear—who’s speaking here?" or “This speech is kind of wordy—maybe tighten it a little?” or “I’m having a hard time believing the character would do that—maybe do something to increase his motivation?” But the man wasn’t interested in the guy’s suggestions regarding his work, so he said “Nope!” He just wanted to make sure everything was legal (spelling/grammar/punctuation-wise) and that was all. He was unfamiliar with the concept of: “The writing is for the writer; the rewriting is for the reader.” So he corrected the objective issues the editor found and globally ignored all the subjective ones. And no big surprise, when reading the subsequent result one might think (a) wow, there are some really clever, unique ideas here, and (b) this thing could use an editor. (If the reader isn’t also a writer, their version of (b) might be more like: Hmm… I don’t find this book as compelling as I thought I would. I have the vague feeling that it could flow better and be more engaging, but I’m not sure why.) But the result is the same—a manuscript which doesn’t do the thematic concept justice, because the writer was unaware that an informed, outside view will almost always yield fresh and valuable insights. (Or he was arrogant enough to think no one else had ideas which could improve his work, but it’s my tale so I’m giving him the benefit of ignorance over arrogance.) But either way, his unique and interesting ideas died a slow death, largely unread, because he couldn’t see beyond saying “Nope!” There’s a vital difference between not liking/not taking a specific suggestion and roundly rejecting the idea of editorial suggestions altogether. A lesson I had to learn when I first became a manager (mostly through watching what happened to managers who didn’t learn it) was that I didn’t have to be the guy who came up with all the good ideas. There’s nothing wrong (and a lot right) with being able to say “Hey wait a minute… that’s a better idea than my idea. So let’s stop the presses and do it your way instead!” Because an effective manager should be able to recognize good ideas and use them, regardless of source. And in some sense, besides being your story’s author, you’re also its manager… tasked with making it as strong as possible. Almost no one likes to be told what to do. (Including me… hence my early love of Nopey.) I get that. But—assuming the editor/beta/critter has at least the social intelligence of a starfish—their suggestions shouldn’t be treated like insults. When someone has an idea (especially one about how to help you make your work better), the first step is to forget the source of it. Next, consider the idea as an idea, with no other preconceptions or baggage. (Imagine you thought of it, if that helps.) Then ask yourself: Is it a good idea? Does it resonate with me? Does it fit the story? Obviously you should conduct this evaluation with the understanding that not all good ideas are necessarily right for your book. Books have a vibe, a theme, a personality… and an idea that’s contrary to the gestalt of the work may in fact harm more than help, no matter how clever it is. Which is why you, as the author, have the final say over which suggestions to take and which to leave. Just don’t be like Gumby’s dog—as adorable as he was—and automatically say “Nope!” to everything.

0 Comments

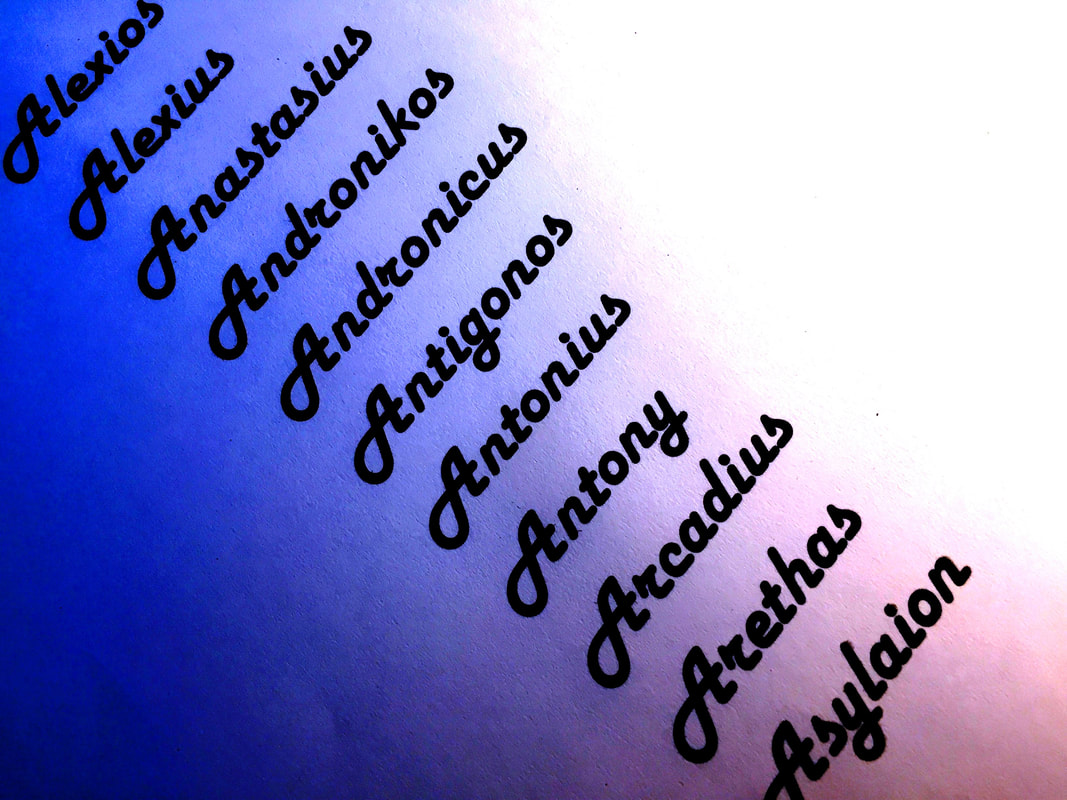

Disclosure: This is a craft-oriented post and might seem a bit “inside baseball,” but I believe it’s important for multiple reasons. (Just one of which: If an agent or editor gets confused about your characters within the first ten or twenty pages, it’s unlikely they’ll read further. Which should be motivation enough to get this squared away.) The subject of character names has been on my mind lately as I’ve recently read a few books which had issues with it. This is one of those areas where we can have a blind spot because after living with them for a while we tend to think of our characters as the specific names we’ve originally chosen for them and we’re naturally resistant to changing things. (Yet another example of the “too close” syndrome which can plague us as writers.) The following are a few things to keep in mind regarding the naming of characters in our work, with the goal always being clarity for the reader (that person who paid for the privilege of reading our words). *NOTE: These aren’t rules (because there really are no rules when it comes to fiction) and I’m not into telling anyone how they must do things. So before each of these, add “please consider the following…” or “you might want to think long and hard before you…” And please don’t send an angry message about some famous character having three different names or whatever. Again: no rules. These are just concepts to be aware of, because whatever wild thing you do with your art, you should do intentionally, not accidentally. With that said… 1. Don’t introduce all your characters to us at once. I recently read a book with an early passage basically saying “… and my brother so-and-so and my little sister such-and-such and my older sister what’s-her-name, and of course my best friend next door…” I ended up bookmarking that page because I’d read a name on page 50 and think, now who was that again…? and have to flip back and refresh. Spread them out if possible—let us see them each in context, doing whatever it is that makes them unique, instead of just another name in a list of names. Closely related to this is: 2. Don’t define a character to us only once. This is common due to the fact that we (as writers) usually have them firmly in mind, and separate from each other. So we intro them and move on, always certain (in our minds) of who they are. The reader doesn’t have the weeks or months of forethought (and likely written notes) that we do regarding the characters, so they need a little help. More than once—in more than one manuscript—I’ve seen an editor comment “remind us” in the margin next to me blithely referring to a character. So if you mention “My best friend Jeri” early on and then we don’t see her for another thirty or forty pages, don’t just casually refer to her again without context. You know who she is, but the reader could likely benefit from: “Of course Jeri would understand—we’ve been best friends since sixth grade, and…” 3. Don’t give characters multiple names. I was again reminded of this last week as I was reading a novel where both main characters had pseudonyms. Within the book, the characters’ real names were used constantly (i.e. on virtually every page) and their stage names were used infrequently (like maybe a dozen times in the entire book). Yet the book was titled using the pseudonyms. I found myself frequently flipping back to either the book cover or the flaps, trying to remember who was who. Yes, there are exceptions to this. And characters working undercover, etc., could—and probably should—have an alias. But referring to a character on a day-to-day basis by multiple names should only be done when there’s a story-enhancing reason for it… and only when it’ll be absolutely clear to the reader who’s who. 4. Don’t have a massive number of named characters. The obvious exception here would be A Song of Fire and Ice, but keep in mind GRRM has a full-time dude just to keep track of the couple thousand named characters in the series (which tells us this isn’t necessarily a goal to aspire to). For us muggles a better goal may be to have enough named characters to keep things interesting and three dimensional, but not so many that neither you nor your readers can follow the story without constantly referring to a lengthy list of cast members (which of course will tend to kick the reader out of the story—definitely something to be avoided). Toward that end, keep in mind not every character needs to be named (that quirky Uber driver we only see once, for example). And sometimes one character can do the work of two. (If you want your MC’s boyfriend to have a mom and you need an oral surgeon in the book, consider consolidating them. Besides saving on names, it can give more depth to the mom.) When introducing a new character and deciding whether or not to give them a proper name, the type of questions to ask ourselves are: Are we going to see them again? Are we—either via narrative voice or through other characters—going to refer to them again? Are we going to attribute dialog to them frequently? If no, then perhaps we don’t need to add them to the roster. Maybe an impromptu nickname instead (“geeky Uber guy”) is enough to get through the scene without adding yet another name to the reader’s mental cast list. 5. Don’t let your characters have names starting with the same letter (or otherwise similar). You see this a lot. Because, like most things mentioned in this post, in the writer’s mind there’s a clear difference between the hero, Jim, and his nemesis, Joe. But—again—probably not to the reader. If you submit a manuscript with a Bill & Bob or a Jill & Joan and it makes it past your agent to an editor who acquires it, you’ll likely be changing that, regardless. Because editors know that when confronted with multiple characters, readers sometimes use mental shortcuts like, Oh yeah, that woman with the ‘V’ name… So either Valerie or Victoria is going to bite the digital dust before the story makes it through line edits. (And authors and editors aren’t immune to the potential confusion, either. I read a passage in a novel where the author was clearly talking about “Jim” [good guy] but called the character “Joe” [bad guy] and the error made it through all the edits and copy edits.) Better to avoid it altogether. 6. Don’t let your characters have long, unpronounceable names. This is particularly common with science fiction and fantasy works. I get why you might not want your book which is set on another world to be populated with people named Brad & Janet or Dick & Jane. But are you sure you really want characters with 7-syllable names that sound like a rare genetic disorder? There’s a balance between the too-familiar and the incomprehensible. Think of some of the more popular characters in seminal SF/F works: Leia, Cersei, Bilbo, Xena, Deckard, Mal, Hagrid, Gandalf, Aeryn, Han, Kara, etc… These are unique enough that they don’t seem like a random group of people right off the streets of West Covina, yet are fairly easy to both pronounce and remember. That’s probably enough Don’ts. Here’s a Do or two: Do give your characters names that seem to fit them, give them their own identity, and resonate with you. But also, do take a minute to look at their names from the reader's point of view. And, of course, you do you. |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed