|

We’ve all heard the fable of the dry branch breaking while the supple limb flexes and comes back stronger than ever. Nowhere is this more apt than in working with publishers and their creative staff. Recently I heard someone talking to his friends about his newly-finished book manuscript. Someone asked, “So when’s it coming out?” and the writer replied, “As soon as I find a publisher that won’t make me change anything!” I was there as a friend-of-a-friend so I didn’t say a word, but what I thought was, So… never, then? Because that’s what publishers do! I don’t mean they alter the meaning of your project or make changes without your approval or anything even remotely nefarious. What they do do is ensure the books they publish are the best versions of those books possible, in the expert opinion of their creative staff (editors, editorial directors, art directors, copy editors, designers, editorial assistants, etc.) who—collectively speaking—have vast amounts of experience in publishing. They earn this right via the simple fact that they’re paying for the production of your book, from your advance to the editor’s salary to the physical printing of the books (to say nothing of the publicity, sales, marketing, and distribution of said books to various venues all over the world… all of which contribute to your bottom line). And beyond that, they’re generally pretty damn good at what they do. (Maybe better than you… definitely better than I.) And they generally know what works in any given market… again, maybe even better than we do. Because of the above, they will actually offer editorial suggestions regarding manuscripts they plan on publishing. And if it becomes clear that you—as the author of said manuscript—aren’t amenable to considering feedback regarding your precious words, you suddenly become much less interesting to the editor in question. On the flip side, if they get the vibe that you’re a talented writer who also plays well with others, that’s a plus. Virtually every story of publishing success I know of involves taking (or at least seriously considering) editorial input at some point. My very first professionally published piece began as a letter to the editor of a magazine. But the more I worked on it, the more it started to look like an article (at least in my naïve opinion at the time). So I went ahead and wrote the entire piece (around 3000 words, IIRC), complete with charts and graphs and photographs. (Which I developed in our little homemade darkroom, indicating what century this was.) Then I bundled up the whole thing and sent it off to the editor without a word of warning. (Query letter…? What’s that?) His response upon receipt of my bundle of literary brilliance? “Sorry, but we’ve already done something like this.” Shit. “But…” he suggested, “how about writing an article about this, instead?” And the this he referred to was something I didn’t have a lot of interest in, to be honest. But hey, this door into publishing—even if it was the wrong door, leading somewhere I wasn’t really interested in going—was open. If only a crack. And it was the first door I’d seen up until then that wasn’t bolted tight. So I took his suggestion and wrote the piece (which he bought and published) and that was the beginning of my nonfiction career, leading to two hundred articles in various national publications as well as a couple of nonfiction books. My first fiction sale went something like this: I submitted a science fiction story to the editor of my favorite SF magazine. (A breathtakingly brilliant story that was absolute perfection in every way, I might add.) His response was basically, “It’s an okay story, but we don’t need to see the protagonist break in and steal his boss’s prize fish. It’s obvious. Just have him leave, and then return with the fish.” Man, I hated that suggestion. Because I loved the fish stealing scene—so clever, so funny, so… superfluous. Yeah, once I removed it (something I never would have done on my own) I saw he was right. So I sent him the revised story, and he bought it and published it. Which was awesome. But even better, I learned an invaluable lesson—just because a scene is “good” (or well-written or funny or clever or whatever adjective strokes your writerly ego) doesn’t mean it helps the story. And the secondary lesson here was that this insight didn’t come from a writer, but an editor. Because that’s what editors do--they make stories better. Not by re-writing them, but by making suggestions to the writer as to how they might re-write them. (Understanding this difference is crucial, lest you fall prey to the goofy-yet-popular “Publishers will totally change your shit and publish it without your approval” myth.) My wife’s first book deal came about when an editor read her manuscript and returned it with a note on the order of, “I like the voice but it’s way too long for the genre. If you cut it in half, I’ll look at it again.” A lot of writers would have thought, NFW am I ripping this thing apart for a major structural rewrite just because one person might ‘look at it again’…! That’s a ton of work with no commitment on the editor’s part, and my wife obviously thought the book was good as-is or she wouldn’t have shopped it. (No agent at this point.) Yet the door—while not exactly open—was at least unlocked. For now. (That’s another thing about rejections-with-suggestions: they come with an expiration date, which is exactly as long as the editor’s memory of her good feelings about your manuscript. Different for each editor, but generally weeks or months and not years.) So (with my loving support and encouragement… most of which consisted of me saying, Are you freaking crazy? Of course you should do this!) my wife buckled down and did the hard work of making the book significantly shorter while keeping the stuff that made it unique and wonderful in the first place. The editor eventually bought it—which started my wife’s career in children’s literature—and they currently have thirty-plus books together… and counting. My first book deal (nonfiction) was also based on suggestions, but in this case it was the writer giving suggestions on the editing rather than the other way around. I’d written a fairly lengthy series of how-to articles for a magazine, and when the series was concluded my editor floated the idea of bundling them up into a book, basically re-printing the articles as they’d originally appeared in the pages of the magazine. I’d had similar thoughts, but I didn’t want it to be just a ‘collection of articles,’ so I suggested I write additional material to bridge each section and gen up additional photos and drawings (as well as change the 3-column magazine format of the text to a more “bookish” 2-column layout) which the editor was flexible enough to agree to. The end result was a coherent book the editor and I were both proud of—it became one of the better selling books the publisher had at that time—and I can’t help but think this might not have been the case had we just put out a quickie compilation. With my first published book-length fiction (a YA novel), there was some editorial back-and-forth between me and the editor before I even got a contract. I recently heard someone opine that you should never do any revisions without a contract (and if your last name is Rowling or King, I might agree) but my thinking is if an established editor at a reputable house is willing to work with me on my manuscript, then I’m goofy not to. Her suggestions were very good—typically more about what to trim than what to write—and I took at least 80% of them. And I ended up with a contract and an advance and an agent and a book I’m proud of. None of which would have happened had I put my foot down in a show of authorial inflexibility. And finally, with the novel I recently sold (actually, which my amazing agent recently sold, to a Big Five imprint), the editor had some questions before she made an offer. She let it be known that she was interested in the manuscript—loved the main character and his voice—but she needed answers first regarding how I might address certain things. I felt she was basically saying, "This is roughly what I think it needs. If you aren't up for doing the work, let me know before we tie the knot." And I totally understood that viewpoint, and I really appreciated her forthrightness. (See this post on how “a willingness to revise” is one of the main things an editor looks for in an author.) Then I proceeded to reply to her with a couple thousand words on how I might address her comments. And, well, here we are—the book pubs this fall and I couldn’t be more excited. And to be honest, I think my general willingness to roll up my sleeves and work with her was as germane to selling the manuscript as any specific revision ideas I came up with. And… now that that manuscript is pretty well buttoned up, we’ve had a conversation about next steps. I said I had ideas in sub-genres A, B, and C, and she said she was more interested in books that fell under B than A or C. Fair enough. So I sent some pages of an idea that came under B, and she let me know what she liked and what she thought needed some tweaks. Again, I’m free to do what I want, but if I want to continue to work with her, the smart move would be to work in an area in which she’s interested and listen to her feedback. So that’s what I’m doing. Begin to see a pattern here? So… if you need a publisher that will put out exactly what you write, word-for-word, without suggesting any editorial changes, that’s easy. You just have the wrong P-word. You’re not looking for a publisher, you’re looking for a printer. There are a ton of them who’ll be happy to take your money and print up your draft exactly as-written. And there are lots of sites where you can “just press publish” and your words will be magically available to whoever wants to read them, exactly as you drafted them. And all of that’s perfectly fine. But if you want to successfully work with a publisher—one who will pay you, as well as pay for the production, printing, publicity, sales, and marketing of your book—then a little creative give-and-take can go a long way. And will very likely make your book even stronger than it would have been on its own. After all, you and the publisher want the same things—for your book to be the best version of your story, and for it to find success, both artistically and commercially. Don’t be so brittle you break. Sometimes there’s more strength in being agile. Happy flexing!

0 Comments

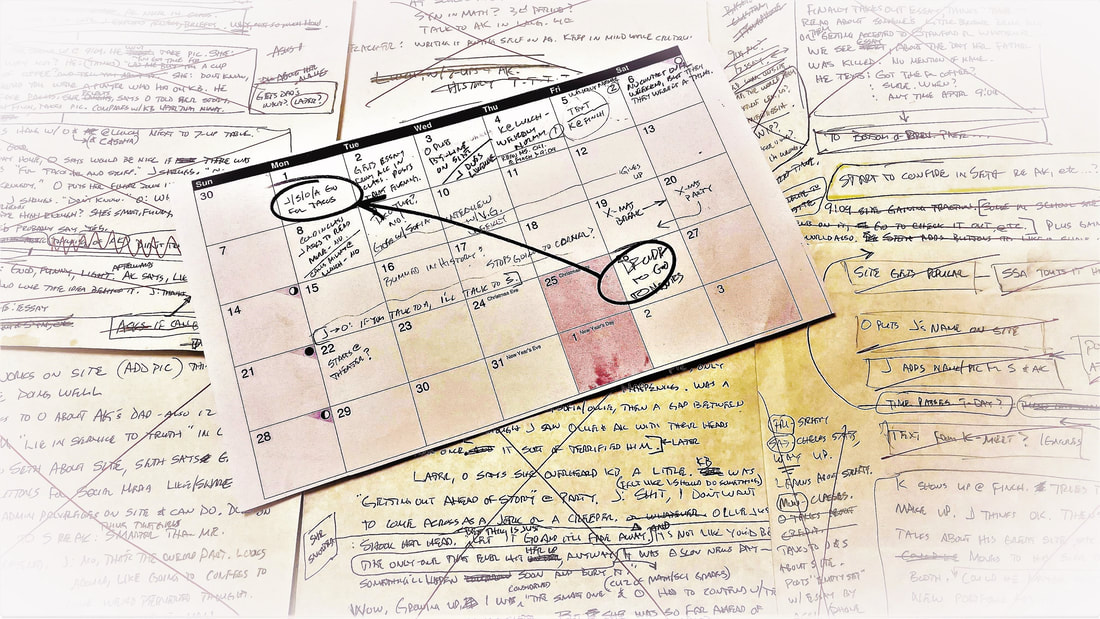

This issue comes up a lot, framed in a lot of ways. Essentially: “How do we manage chronology in our stories, vis-a-vis the narrative point-of-view?”* ******************************* First caveat: I’m no expert. In fact, there are no experts on this. (However, there are people who supposedly know all the “rules”—and have the paperwork to prove it—but in my experience you don’t want to take writing advice from them.) Because… Second caveat: There are no rules. This is art, not science, right? Whatever works, works. Third caveat: I can only tell you what works for me, and maybe a few other writers I know. You need to try things out and see what works for you. Your solution may be different than mine, which is wonderful. ******************************* [*For me, the only meaningful answer to this question is some version of: In a way that feels smooth and natural and transparent to the reader. That’s all that matters. All else is low-signal and high-noise.] Let’s look at the most common example: managing flashbacks. The very first issue to consider: Does the benefit of the flashback outweigh the cost of removing the reader from where she is and flinging her somewhere new, then waiting for her to get acclimated to the new place, then bringing her back to the present? That’s totally up to you, but overall I’d say there seems to be a tendency for newer writers to want to put flashbacks into their early pages because they think the most important thing is that the reader understands everything from the get-go. That’s not really the goal… the goal is to get the reader immersed in the character/scene to the point where they’re invested in the character and the story feels real to them. If you do that, they’ll follow you anywhere. (And of course they’ll expect you to catch them up a bit at a time as you go along, and you should hold up your end of the bargain and do just that, but not at the expense of throwing them out of the story by info-dumping or jerking them back and forth in time just so they have “all the facts.”) In brief: Information is not nearly as important as interest. But sooner or later—when the reader knows the character and the time/place in which they reside—you may need to jump back and show them something important that happened before the story started. In the above sentence, the operative word is “show.” That’s why we use flashbacks… to show a scene instead of just telling us, Six months ago, X happened. If you can simply tell us that and it feels natural and doesn’t interrupt the flow (and we don’t need a high level of detail) then by all means, do that. But otherwise, the goal of a flashback should be to make it feel like part of the story, not like a separate, non-story event. While still making us aware that it happened before the present story time. One way to do this is to have the POV character say or think something that relates to previous events; have a scene break; set us clearly where—and when—the back-in-time scene happens. And then… Then… if you’re going “by the rules,” you would use the past perfect tense to describe everything that happened in the past. (Ex: “I had done this, then she had done that, and then we’d decided to do this other thing…”) Which is 100% correct, except… (and feel free to insert f-bombs for emphasis as you read this) it doesn’t feel like story—it feels like someone telling you what happened. Which is in violation of the ‘how do we do it?’ answer, namely: In a way that feels smooth and natural and transparent to the reader. So instead, consider tossing the rules and not doing the whole ‘past perfect tense’ thing. Instead, consider completing the three pre-flashback steps above, then starting the body of the flashback with one or two uses of past perfect tense, then segueing into regular past tense for the duration of the flashback scene (assuming the rest of the book is in past tense, of course, otherwise use whatever you’re using), then another mechanical scene break, then bring us back to the present with something (action, dialog) that takes up where the pre-flashback scene left off. For an example, let’s make up a goofy little origin story which transitions present-past-present (as origin stories are wont to do)… ### ### ### [story, story, story…] …and as I crested the hill it occurred to me that riding a blazing unicycle from hell felt as natural to me as riding a bicycle did to most boys, but it sure wasn’t always that way… * I’d wanted a unicycle for as long as I could remember, but I’d never expected Krampus Himself to conjure me up the Flaming Wheel of Fire on Krampusnacht three years ago. I woke early that morning—well before the sun—expecting the usual oranges and walnuts and such from Saint Nicholas, because I’d been “good.” (Well, except for that episode with Petra in her father’s barn, but we’re not talking about that.) But I guess that horned asshole knew all about it, because he showed up instead of Ol’ Nicky, and instead of treats he had a bundle of birch rods for whipping my bottom, along with a fierce grin... indicating he was going to enjoy said whipping rather more than I. In a moment of terror-inspired brilliance I held up a finger, quietly reached behind the pantry curtain, and brought out a jug of my father’s favorite schnapps and a couple of stone mugs. “You can whip me and carry me off,” I offered, “or you can have a drink. Your choice, my good sir.” Well, everyone knows schnapps is Krampus’ second-favorite thing, so pretty soon we were knocking 'em back like two old mates down to the public house. “So, what do ya really want, my boy?” he rumbled. Leaving that frighteningly possessive pronoun aside, visions of oranges and chocolates flew in one earhole and out the other. “Well, sir…” “Drop that sir shit!” he boomed, half in his cups already. I took a swig. “Well, Krampy… what I really want is a unicycle.” “A unicycle???” I was certain he’d wake my parents, but you don’t just shush Krampus, now do you? I bobbed my head. He rubbed his hands. “But it’d have to be a… special sort of unicycle, wouldn’t ya think?” No, I did not think. But I just nodded again. What would you have done—argue with him, I s’pose? He reached into his big black bag—I could just make out the mewling of some of the less-quick-on-their-feet village boys—then pulled out a feathered pinecone and flung it into the fireplace with such force that it cracked a brick. After the smoke cleared and he’d disappeared—precisely as my parents awoke—standing of its own accord in front of the hearth was my singular wish. Already alight. * As I barreled down the backside of the hill, I had to give the devil his due… that fiery rocket of a monocycle has changed my life in ways I couldn’t have fathomed back when he first gifted me—or cursed me—with it. In fact, waiting for me at the bottom of the hill was… [story, story, story…] ### ### ### TL;DR: (1) POV thinks/says something related to the past; (2) use a mechanical scene break of some kind; (3) anchor the flashback early in the scene; (4) maybe use a little past perfect—if at all—then; (5) dump it and get back into your normal tense (which will feel way better to the reader), then; (6) use another mechanical scene break, and finally; (7) anchor us firmly back in the present with a familiar or expected action. Or… use any other methodology of your choice. I think the cardinal thing to keep in mind here is that a flashback should be a scene, and the sooner it feels like a scene and not an info-dumpy chunk of exposition, the smoother and more natural it’ll feel to the reader. And, therefore, the lower the cost of diverting the reader from the present to the past and back again, which is all to the good. Happy flashingback! |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed