|

The more I pay attention to it, the more I begin to believe that one factor may be more important to producing quality work than any other: The ability to recognize it. And taking it one step further, the ability to recognize its absence. And finally, the ability/willingness to replace <non-quality work> with <quality work>. The above posits two things: 1. We can produce quality work at times. (This seems to apply to every single writer I know.) 2. We are imperfect, and don’t always produce quality work. (This also seems to apply to every single writer I know.) Therefore, we can do good work, yet we don’t always do good work. Why is this? I mean, wouldn’t we want everything we do to be “quality” work? I believe it’s partially because we don’t always take the steps necessary to recognize when we’re not doing quality work. This takes time, effort, and an understanding of what constitutes good work*. [*I realize this opens the huge can of wildly subjective worms known as: What is good writing? We’re certainly not going to solve that one here, and far be it from me to set the bar for this, regardless. So for the sake of this discussion, let’s loosely accept “Writing which you and agents and editors and publishers and especially readers believe does an effective job at conveying the story such that it feels like ‘lived experience’ to the reader. It doesn’t take the reader out of the story, or get in the way of the story, but instead presents it as an emotional experience that feels real – at least in the moment – to the reader. Regardless of the type of story.” Let’s go with that for now… ] One could undertake a focused study specifically designed to help them recognize, understand, and—hopefully—produce quality work in fiction. (There are a number of MFA programs aimed at exactly this. Some of them are even genre-focused, such as a deep dive into kidlit, etc.) Some writers take this path, and some have good results with it. In my view, any educational experience that asks the student to look deeply into why something works or doesn’t work is likely to be beneficial on some level. (And aside from that, there are lots of other opportunities to study the craft both within and outside the traditional educational environment.) On the opposite end, you could simply read with abandon – broadly, deeply, and at a high volume. This—although usually done without the knowledge at the time that it’s great training for being a writer—is how many of us learned the fundamentals of the craft. If we’ve spent a significant amount of time reading as described, it would be hard not to absorb and internalize at least some of the precepts of “good” writing*. (This assumes we’re reading “good” writing, but again simplifying for the sake of discussion: We’re very likely reading what we will later want to produce—publishable fiction that we like in a genre with which we’re familiar. Which is close enough for now.) [*Synchronicity! I just read an interview in a separate-yet-still-creative field (audio mastering) which said, about the same concept, “There is something that comes from that level of immersion where the depth of what is absorbed cannot be fully articulated. It is the repetition, the problem solving, and the law of big numbers. Smaller samplings don’t reveal as much information…” I couldn’t agree more.] This doesn’t automatically make us a good writer, any more than being a music lover automatically makes us a good musician. But at least it gives us a critical bar to aim for. In the hierarchy of self-knowledge, going from “unconsciously incompetent” to “consciously incompetent” is a massive step in the right direction. (Because once we know we need to improve—and where—we’re on your way. But until then, we’re sort of stuck.) Taking the music analogy a little further, when young musicians first learn how to play, they almost universally work up a set of cover tunes—they learn to play popular (and generally good) songs, by popular (and generally good) bands. They’re not doing it as a conscious study of “what the greats of the field have done before us.” They’re not doing it as a study at all. They’re doing it because (1) it’s fun to play cool tunes, (2) they want to jam with friends, and it really helps to have some agreed-upon songs they can all play, and (3) they want to gig, which means they have to learn and play songs other people want to hear. Yet in this process they’re also unintentionally giving themselves an education that’s vital to continuing their musical journey. (And as a counterpoint, occasionally you’ll hear a competent musician try to play a song in a certain style—funk or country or blues or whatever—and it’s clear they haven’t ever really listened to that genre.) You see this sometimes with writing. You’ll read something by someone with the ability to put together well-written sentences, yet when you read it, you might think: Have they ever even read a romance (or SF or mystery or YA or whatever)…? Because it’s written in a way that indicates unfamiliarity with the canon. (And consider the following: whoever reads your Romance/SF/Mystery/YA novel will likely have already read a ton of Romance/SF/Mystery/YA novels… even if you haven’t. And they’ll be comparing it to everything that’s gone before. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be unique, but there’s a significant difference between “new & unique” and “misses the mark.”) And finally, you’ll sometimes see a manuscript containing good writing (however we define it) followed by a patch of over-baked, cliched writing. And the question here might be: Can they not see the difference between this stuff right here and that stuff over there, only three pages away? I’m going to suggest that maybe they actually can’t. At least, maybe not in the moment. And the reason for that may be that they spend a certain amount of their reading time perusing work that has the very issue described above. Which can have the opposite result as the “raising the bar” effect that can come from reading really good stuff. I’ve personally noticed a phenomenon where if I’ve recently read a fair amount of “not so good” work (however we define that), my own writing seems to suffer. I’m not sure exactly why, but the effect seems to be real. Maybe it sort of de-calibrates my “quality compass”…? (Imagine if you watched a whole bunch of subpar, student-made, cliché-ridden slasher films, then set out to make a moving, nuanced, coming-of-age film? I’m guessing you might be better off studying the masters, instead.) Which is why I not only say ‘Read Good, Write Good,’ but also… perhaps… ‘Read Bad, Write Bad.’ Sometimes a producer, during the pre-production phase of making a record, will distribute a list of records for the bandmembers to listen to prior to going in to the studio. Maybe records that have a certain vibe or quirkiness or sophistication (or whatever aspect the producer wants to spotlight). This is not in an effort to tell them, “Let’s play music just like this!” It’s more to give them an overall bar to shoot for… often the records are in a completely different genre than the record they’re going to make. (Which is all the better, as copying it is completely off the table.) So… perhaps we can do likewise if/when we find ourselves a little adrift regarding being able to self-critique our own work for whatever reason. Prior to starting a recent realistic/contemporary novel, in an effort to calibrate my “What does good look like?” meter, I read a book in a totally different field (magic realism, in this case). It was very different from my work in a lot of fundamental ways (character, voice, vibe, plot, etc.) but it was brilliantly written, it let me know what was possible, and it sort of put me in the frame of mind to try to “get out there and do good work.” So… happy reading!

4 Comments

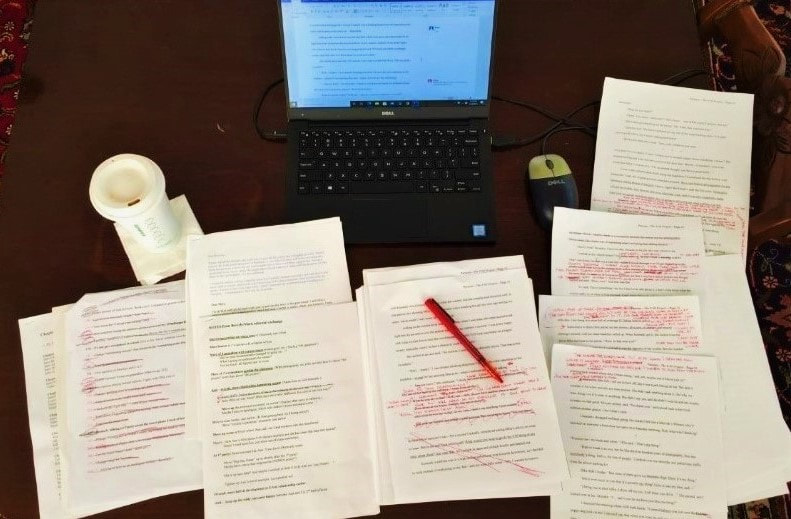

People often say, “Are you a process person or a results person?” To which I usually answer, “Yes.” Which is true in a couple of ways. Yes, I enjoy both the process and the results of creation pretty equally, with some obvious exceptions. (The process of original drafting is pretty damn magical, regardless of where it ends up… while the process of a structural rewrite can be painful but the results can be very rewarding.) But beyond that, I’ve learned that the process can actually help determine the results. I’ve also learned that process is specific to the individual, and it’s a mistake (and a little ego-centric) to say that because something worked for you, it will therefore be the best for someone else. Because writing (and music and dancing and filmmaking and…) is an art, not a science. And because we’re all a study of one. However, there are still a few valid things we can say about process… 1. We can say, “This worked for me,” and explain why, followed by, “…so it might work for you, too. Or not. But it may be worth a try.” 2. We can say, “Here are several ways people have done this, successfully, so you might want to try them and see if any of them fits your workflow.” 3. And we can say, “Regardless of which one you use, recognize that process is important. So if the work isn’t working, before you bail out and think that you’re bad or your idea is bad or your writing is bad… maybe try a different process.” That last one is important. Not all processes work for all people. Sure. But it’s also true that in most cases, no single process will work for all projects by the same writer. I have a process I’ve dialed in over years that works well for articles, but I used a very different process for my non-fiction books. For book length fiction, they’re all somewhat different.* [*With my first novel (still in the trunk, thank God) I made a detailed outline. But with the next one—my first published novel—I had a character and a setting and a basic conflict and an idea about where it was going, and away I went. With an SF novel, I took a short story I’d written earlier and morphed it into the first chapter of a much longer story. With the novel I recently sold, I’d just finished work on another project and still had the bug to write, so I just jumped in the next day and started writing with no plot in mind whatsoever… just a character and a vibe. And with the one on deck after that, I imagined a funny scene (just a funny line, really), made that the inciting incident, and went from there. I knew the ending—sort of—but much of the middle was discovered en route.] So again, when the muse is on strike, don’t automatically assume there’s something fundamentally wrong with you or your writing. In my experience—both with my own work and the work of others—most of these issues are process-oriented. You can’t change who you are (and you’re the only you, regardless, so revel in that) but you can change your approach to how you’re doing the work. It may be something pretty big-picture, like… Issue: You’re floundering and constantly backpedaling/deleting/rewriting. Underlying cause: Maybe you’re unclear about where you’re going. Process change: Take off the “pants” and put on some “plot.” (Make an outline.) Or more stylistic, such as… Issue: The work doesn’t connect because it’s overwritten. Underlying cause: Maybe you’re consciously trying to write “writerly.” Process change: Get out of the way of the story and tell it plainly. Or maybe business oriented… Issue: Striking out with multiple projects in quick succession. Underlying cause: Maybe you’re submitting too soon, before it’s ready. Process change: Finish; let sit; tear into it like you didn’t write it; beta; revise; polish. And so on. The point isn’t to diagnose every possible process issue with our writing. The point is to recognize that when we’re not getting the results we want, the answer might not be to blindly follow the same process, like there’s only one way to do it. Instead, the answer might be to take a step back, appraise the situation objectively, and try to think of different ways to approach it. Sometimes it’s as simple as how we think about the work itself: Maybe my project’s not a YA book, it’s a middle grade book? Or: Maybe it’s not a memoir, it’s an historical novel? Or: Maybe I should dump the magic and go with the strongest part of the story, which is the contemporary/realistic aspect? Or our marketing approach: Maybe, since my work is an ‘amateur female detective’ mystery, I should read a bunch of amateur female detective mysteries, find the ones that are a good fit for mine, and make a targeted, personal query to the agents/editors who worked on those books? Or: Maybe I should give the person at the other end of my query what they actually care about (a concise, compelling description of my story) instead of talking about me and my ‘brand’ and my ‘platform’…? Or: Maybe I should shop the story that means the most to me, vs trying to catch the flavor of the month as it goes zipping by? Or the nuts & bolts of how we actually write: Maybe, since I’m not at my best when I get up an hour early every morning, I should forget all that ‘write every day’ advice and instead set aside a few hours each weekend when I feel motivated and productive? Or: Maybe, instead of not putting on the editor hat until I’m done with the whole draft, I should try editing each chapter as I finish it, so I’m building on a stronger foundation? Or: Maybe I should forget about the hypothetical reader and write a story that I, personally, would love to read? OR… maybe… you could take some of the above options and use them as a jumping-off point and do something entirely different… different from what you’re currently doing, and different from these examples. Maybe the opposite of these examples. That’s the whole point – there is no ‘one right way.’ But there is a way (probably several ways) that will work for you. You just won’t know which one it is until you try it. Happy writing! |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed