|

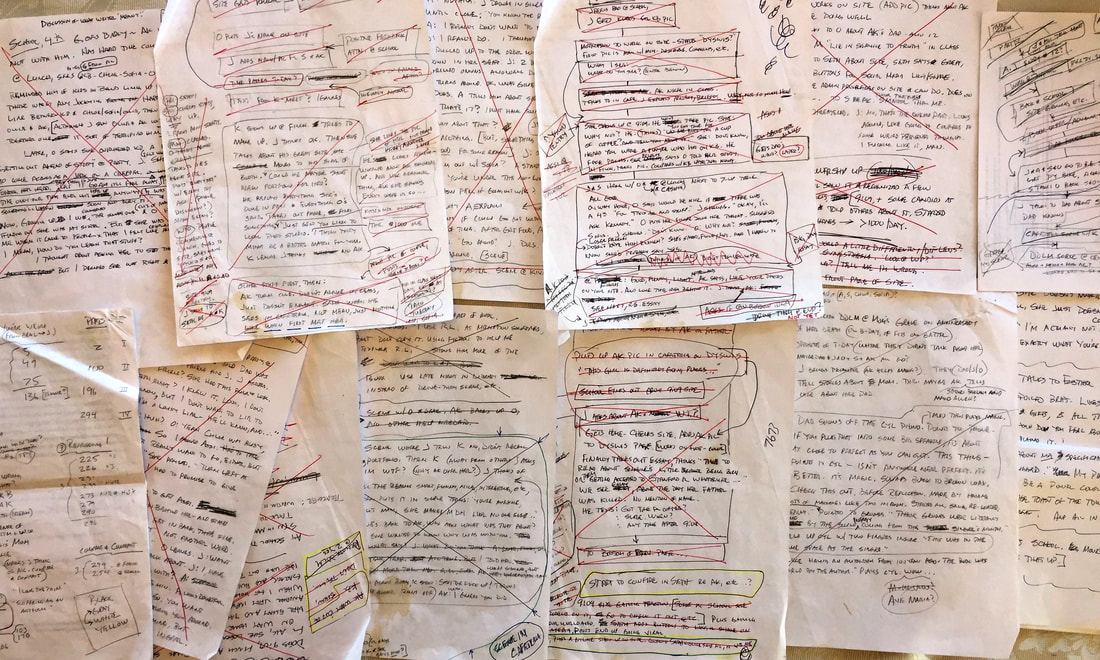

Example A: For various reasons I recently clocked several versions of “Pride and Joy” by Stevie Ray Vaughn. Virtually all iterations—including the official studio recording—start around 120 bpm but eventually end up (after multiple verses and solos) around 128-132. And no one minds. Or even much notices. Because it totally works, on an artistic level. Yet were you recording something like this today for a commercial label, there’s a good chance they’d have you record it to a click track (which keeps the tempo absolutely steady). The theory behind using a click is that music supposedly sounds better if the tempo is metronomically perfect. And, arguably, some types might. (Electronica and variants thereof come to mind.) But in practice, the real benefit of using a click has almost nothing to do with the music itself. It’s for the convenience of the producers, because it allows them to edit with impunity between different parts of a take, or between different takes. So the art is fundamentally changed for administrative reasons, rather than the other way around. Example B: Some pretty high-tech people have recently posited that—for time management/productivity purposes—it may be beneficial to write all your tasks on a large physical calendar where you can see everything at a glance. Using a scheduling app on your phone/tablet/computer is great, but when you can see it all at once, laid out in front of you, your brain apparently gets a better overall picture of how to manage your resources. Example C: There’s evidence that hand-written lists may be some of the very best productivity tools available. The act of making/updating/adding/crossing off seems to keep the brain engaged in task completion, and—as with the calendar concept—simply having it in front of you can help you wrap your head around it. Furthermore, just physically writing things down seems to help plant them in our memory differently than reading them or entering them via keyboard. Anecdotally only, all of the above ring absolutely true. For me. And for my workflow. I’m happy to gen up a click in the studio if someone wants or needs it—and I’ll play to it—but I’m aware of the artistic costs and I’m also happy to fly untethered, assuming everyone can play together nicely. I used scheduling tools daily in my corporate gig, but I also was a huge fan of the “big calendar.” (I once made—and pinned up in the office—a really large calendar of the entire upcoming year, with all known events on it, including who was supposed to be doing what, when. You wouldn’t believe how many times I’d see people standing in front of it, holding an impromptu brainstorming session.) And we definitely live by the written list around here. We even joke that if we complete something that wasn’t on the list, we should write it down then immediately cross it off. And then we’ll do exactly that. Because if the act of doing so causes something positive and productive to happen in our brains, who are we to argue? The overall point here is (a) there are many different ways to accomplish any given task, and (b) there are many different tools available. I believe it’s helpful to determine your working methods, so you can determine the best tools for you. Regardless of what anyone else is doing. I used to write mostly by hand, in notebooks. Because much of my writing happened where a computer wasn’t available, and because I was a poor typist. (Somewhere I have a box full of old 6x9 notebooks filled with my handwriting, much of which became published articles, and much of which were typed up by my wonderful wife.) When I bit the bullet and decided to write all initial drafts on a computer not only was my wife happier, but my writing improved. Because—against conventional wisdom—I often wear both “writer” and “editor” hats as I write, and if I compose a bad bit of writing I have difficulty moving on until it’s at least serviceable. On the computer change is fast and easy, so I can rapidly do a first-pass edit at the end of a paragraph or page or scene, then charge forward again. I know this isn’t the norm, but it’s how my brain likes to work so I accommodate it. A similar discussion arises around writing software. You’ll see online arguments raging over the “Word vs. Scrivener” debate (or similar) and it invariably follows this script: Player 1 will point out all the things right with Brand X and everything wrong with Brand Y, and Player 2 will do the exact same only in reverse. I think someone’s missing the big picture in these discussions. Not that the tools are the same, but that we (as writers) are different. Because when it comes to art, “This is better” is meaningless. Unless you add “for me.” So, analyze the way you work. If your brain needs to know details about where it’s going before it can get there, if it likes to think of “story” as groups of discrete scenes, if it likes to play around with scene arrangement before or during story creation, then you will very likely have better results with writing tools which use the “3x5 card” paradigm and allow you to construct, edit, and re-order scenes at will. On the other hand, if you’re the old school, strong willed type who gets a rough idea then writes linearly until the end with no real revising before the first draft is finished, you could use a typewriter and get the same results as using the most sophisticated software. (William Gibson used a manual typewriter to write Neuromancer. If that’s not irony, I don’t know what is…) And if you’re old school and a serious plotter/arranger, you could use real 3x5 cards pinned onto a corkboard. This can actually work pretty well, as it leverages the benefits of the “see it all at a glance” thing we mentioned earlier, and can be rearranged at will. Personally, I’m somewhere between a pantser and a plotter, and Word has the right balance of simplicity, directness, and functionality… for me. (Or, to put it another way, when I have writing problems they almost never have anything to do with the tools I’m using.) However… when I’m making notes (of the planning/pondering/plotting kind) it works so much better for me when I write them by hand. And it seems that the more informal (read: quick and dirty) I make the notes, the better. Not only better for actual content, but the better for flow. Which, when spinning ideas out of nothing, is perhaps more important. The best methodology for me is to staple a dozen or so blank pages together—no formal notebook or even lines on the page—and just start scrawling. I’m guessing this works because it sends a signal to my subconscious that this is just play… almost throw-away… which frees up my mind much more than using a fancy notebook which says, This Is Important! Perhaps—for me—it’s harder to be free and creative when I think the results have something really important riding on them, and/or have to be really good right out of the box. I’d rather tell my brain: This doesn’t effing matter. I’m simply blue sky spit-balling, just for fun. Nothing to see here… move along. I’ll draw a wavy line after a discrete section, to delineate scenes or passing time, but that’s about it. And when an idea comes, I’ll work down to whatever level of granularity my brain will support, until the tank is dry. Sometimes, if I really get going on a scene, I’ll find myself writing actual dialog in what should be my “big picture” plot notes. (Truth be told, my brain probably doesn’t care about the big-picture concept as much as the small-picture, character-oriented stuff. So I go with that.) And I’ll keep on doing it until I’m out of ideas for the moment. Then the next time I sit down to write, I have some tasty little ideas scratched out, and I get the (for me) exquisite fun of breathing life into them. All of this works pretty well. For me. And would almost certainly be an absolute fail for a pretty large percentage of other writers out there. Which is the real point here. Don’t get hung up on other writers’ processes. Unless you’re really lost in the wilderness, I wouldn’t spend a lot of time or energy worrying about which specific tools or methods other people are using. Because, by definition, they are other people. They’re not you. What matters is what remains after the process is finished: the story. Your story. The one that only you can tell. So tell it in a way that works for you, using methods that help you get your best work onto the page, whole and intact. Older isn’t necessarily better. Newer isn’t necessarily better. Cheaper isn’t necessarily better. More expensive isn’t necessarily better. Only better is better. Do what’s better for you.

2 Comments

Various studies have shown that something on the order of 80-90% of American adults wish to write a book. Which is perfectly fine, except… Surveys also show that 27% of American adults didn’t read a book at all in the past year. And 40% of them didn’t read a fiction book in the past year. And of those who did, many only read a handful. So in essence, significantly more people want to write than want to read. Which is analogous to someone saying they want to be a musician but they don’t want to listen to music. I think this hubris comes from the fact that the vast majority of adults can write, in the functional sense—they can compose a work memo or social media post or email, and for the most part it’ll be comprehensible. Most of us can do this by middle school. (Which, not coincidentally, seems to be where reading peaks out for a lot of us. An issue definitely worth discussing at some point.) So there may be some sense of, I already know how to write—I learned that in school. In full denial of the fact that there is a craft to writing which goes way beyond obvious things like spelling and punctuation and being able to diagram a sentence. (Similar to how being able to operate the basic controls of a car doesn’t automatically qualify one to enter a NASCAR event.) Note I’m not suggesting we need an English degree or MFA or anything along those lines in order to write. (But if so, fine. You do you.) I’m simply saying we need the recognition that there is a craft to be learned. The good news is, much of the pertinent info is available right in front of our eyes, for minimal cost. The amazing learning devices containing this information are called books. There are of course non-fiction ones specifically written to help aspiring writers better learn the fundamentals of writing. (See this post for a round-up of some of our favorites.) But beyond that, the best teachers of all may simply be well-written books in our chosen genre. Because with books (as opposed to some other art forms) we can literally see the smaller components the artist combined to create the entire work. Sure, there are behind-the-scenes things that influenced the finished work, like early drafts and editing and revisions. But when it comes to the actual words the writer used to craft the final story—how they were chosen and arranged and punctuated and emphasized and ordered into sentences and paragraphs and chapters and sections, well… it’s all there in front of us, in black and white. So we should read. But not like a reader… like a writer. Read well. Read deeply. Read widely. Good books don’t happen by accident. (Just like overnight successes don’t happen overnight.) They’re created by talented writers working to the best of their abilities for significant periods of time, writing and revising and polishing until it’s as good as they can make it. Then further tightened and smoothed via the editing process prior to publication. Well: First: What’s a good book? That’s an endless discussion, but in this admittedly narrow context a working definition might be: the type of book we’d like to write. I suppose it wouldn’t hurt if the book were somewhat successful on some level (critically acclaimed or sold well or award winning or considered exemplary of its genre or whatever) but beyond those third-party accolades, perhaps the most important quality is simply that we like it. Deeply: Next: We should find these books within our desired writing area and immerse ourselves, reading wheelbarrows full of them, paying attention to the how as much as the what. (What they have to say is important, and—for many readers—it’s paramount. But how they say it—for writers—can be a masterclass.) At first we’ll learn what the common tropes of our chosen area are, then as we delve deeper we’ll notice how good writers either avoid them altogether or turn them on their heads and use them in fresh ways. Also, we’ll learn what’s possible, where the boundaries are, and when they can be broken. (When I see someone saying, “I want to write a YA but I have a problem because I want my characters to [have sex / swear / smoke weed / whatever] but I don’t want to turn publishers off with mature content…” I think, Dude, you clearly have not read a single YA novel published in this century… show some respect for the field, por favor.) Widely: Then: We should broaden our stylistic view and read outside our genre. Not just slightly off the chosen path—like going from mysteries to thrillers—but completely different, like going from contemporary romance to biographies of nineteenth century innovators. Read authors from different cultural and geographic backgrounds… covering different subject matter… with different points of view. My dad used to go to our local library and find a loaded returns cart, then grab the first five books on it and take them home. Not all were wonderful, of course, but it forced him to read broadly without a lot of selection bias (other than that someone, somewhere, recently thought the book in question was worth looking at). We could do worse. All the above will feed into our writing, improving and deepening and broadening it. I’ve heard people say they don’t read because they don’t want any outside influence on their writing. If nothing else, being aware of previous work in our genre will help us avoid overused tropes, clichés, and devices that would otherwise be a flaming “keep away!” sign to editors and agents. (Fresh work is wonderful, but work that implies we have no knowledge of our field… not so much. It’s important to learn the difference.) But besides the practical reasons we’ve discussed, probably the most important reason writers need to be readers is that, almost universally, good art is done by people with a deep love for the art form. (And conversely, almost never by people looking for a quick buck.) Reading will help us discover what we love about literature… not just what genre or style, but which aspects of the written word resonate with us. Are we drawn to well-rounded characters? Quirky dialog? A detailed, well-conceived plot? Realistic, slice-of-life writing? Interesting descriptions of new-to-us locations? Lush prose that sings like poetry? Or maybe an economic turn of phrase that contains volumes within a single sentence? And this romance with reading, of course, will help us discover what we’d love to write. It’s all there, right in front of us, in black and white. Happy reading! |

The Craft and Business of

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed