|

The query. It’s important. But… No one ever got a book deal from a query. Seriously. This shouldn’t be a controversial statement but with today’s focus on “the query” as the be-all and end-all of becoming published, it might take a few by surprise. But I stand by it—no agent or editor ever read a query letter and said, “This is such a great letter! Let’s send them a contract, this minute!” So as a follow-up to our previous post I thought it might be worth discussing the concept of: What does a query actually do? There is one primary job, but first let’s break it into a few sub-tasks… 1. It lets them know the meta-data around your book, so they can quickly assess if they even want to consider it. If an agent’s MSWL clearly states “No kidlit” and your query starts with “My middle-grade novel is…” they’ll delete it on the spot and move on to someone who can follow basic instructions. 2. It lets them know if—at a minimum—you possess the basic writing skills to construct a common-sense, readable, compelling cover letter. (As one newer agent recently said, “If you can write a coherent query letter it automatically puts you ahead of 90% of the other querying writers.” And as agent Erik Hane [from the ‘Print Run’ podcast] has said more than once, “A query letter is just a business email.”) Because if you can’t, there’s no point in looking at your pages even if all the meta-data is on point, right? 3. Besides giving them the pitch for your manuscript, it lets them know if you know the important highlights of your book… the character, the setup, the central conflict, and the stakes. If you can clearly delineate these things to them, it gives them reassurance you know something about crafting fiction, and… 4. It lets them know if what you’re offering is in their wheelhouse. If they’re interested in book club fiction about family drama and your pitch starts with “My 80,000 word upmarket women’s novel follows our thirty-year old protagonist who left home the day she graduated from high school but now has to return to her wildly dysfunctional family because she just got word that…”, then the agent is likely to think: This sounds like my jam, and turn to your pages. With the above in mind, there are a few simple ways to concoct your query. A common one is some version of the “Hook, Book, Cook” format, which basically goes as follows…

The entire query should be the equivalent of a one-page business letter. (Shoot for under 400 words, shorter being better. If you can cut something and it doesn’t detract from the desired outcome then by all means trim it!) About that desired outcome, always keep in mind the singular objective of your query letter: It leads to the agent/editor reading your sample pages. That’s all. But assuming you’ve done your job with crafting your story, that’s enough. No matter how great your query is or how much time you spent poring over it, if they turn to your pages and they don’t fall in love with (a) the voice, and (b) the actual writing itself, it’s almost certainly going to be a pass. But a straight-forward query (as long as it tells them enough to get them to read your pages) can absolutely lead to what you’re looking for. As I’ve mentioned before, the query is the taxi or rideshare that took you to an important job interview. Yes, it’s important to get to the interview on time and in one piece, but once you’re in the room with the panel, the vehicle that got you there is immaterial. So by all means, have a good query that places you and your work in the best light. But don’t spend an inordinate amount of time and anxiety trying to concoct the perfect query. There is no such thing. Put most of your efforts into what really matters, the thing they will ultimately say yes or no to… the pages. Which we will discuss next time. Happy querying!

0 Comments

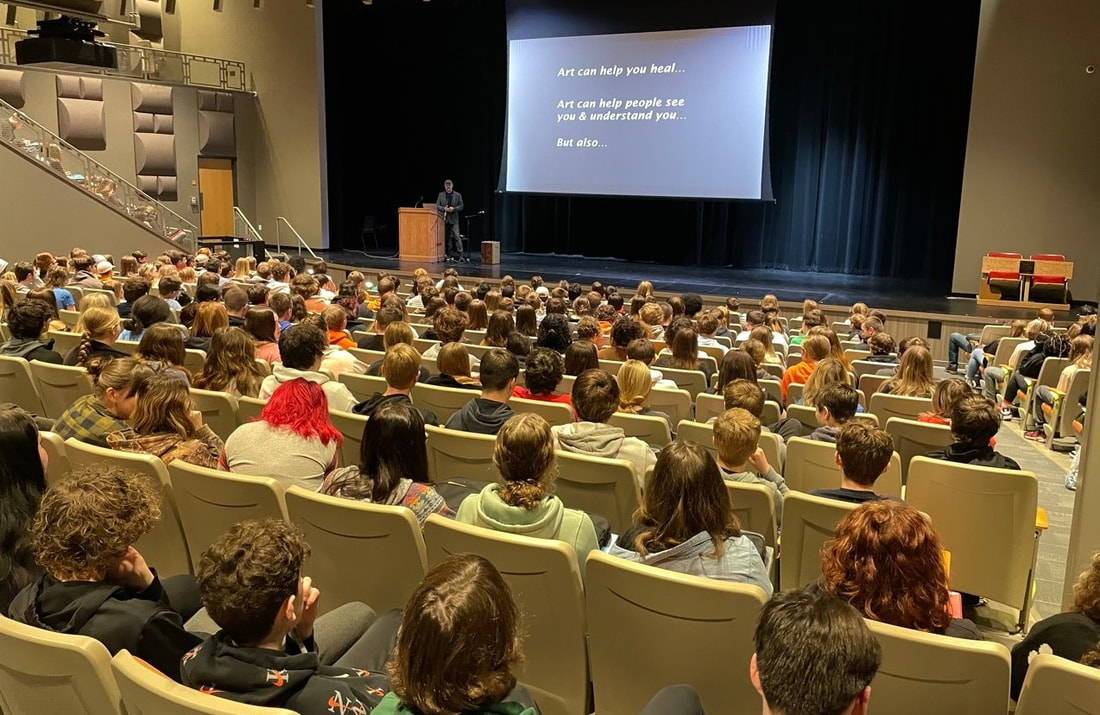

There is “the theory of” and “the planning of,” but sooner or later you’re faced with “the doing of…” A typical day on book tour might start with packing up* and checking out of the hotel, then traveling to the next stop where (assuming you’re a PB/MG/YA author) you may have a mid-day school visit. [*We learned early on not to unpack and put clothes in the dressers or closets. Suitcases on suitcase stands are way more efficient and you won’t leave things behind. We prided ourselves on how quickly we could move in or out, humming the “Mission Impossible” theme while doing it.] These days you should add an extra fifteen minutes when presenting at a school, because you’re almost certainly going to have to visit the admin office first (at many schools, there is no other way to physically access the campus) and sign in, receiving a visitor’s badge. Then they’ll get the librarian or teacher who coordinated your visit to escort you to the auditorium/cafeteria/gym/MPR for your presentation. Go to the venue and prioritize getting the tech up and running before doing too much meet-and-greet. Almost all schools will have someone to help with this, and they range from total tech wizards to flustered/overworked teachers who aren’t familiar with the equipment. Pro tip: have your presentation available on a thumb drive for use and backed up on your computer as well as in one other location, preferably online. (Or vice versa. We try to use their equipment and present off our thumb drives when possible, but more than once the day was saved because we had our computers with us. Multiple cables & adaptors to interface between your computer and their projector/system are worth their weight in gold. I also bring a small USB “pointer/clicker,” because there’s nothing that kills the flow of a presentation more than having to run back to the computer to advance each slide or waving at someone to change slides for you. And finally, be able to give some semblance of your presentation without any technology at all, because sooner or later you’ll have to. Trust me on this…) You’ll want to have an educational component in your presentation (teachers, librarians, and principals will appreciate this—you’re at a school, after all) but also something entertaining for the kiddos. And while you definitely want to talk about your work at some point, what you don’t want to do is simply show all of your books and give a sales pitch for each. (No one will like this approach, adult or student.) Don’t forget to give credit to the store that selected the school. (My brilliant wife makes a slide for the top of each show that basically says, “Sponsored by XYZ Bookstore” with the store’s logo, and this is up when the students are filing in. Often the store will have a rep at the school, either to watch or to hold a sale afterward. They always appreciate the shoutout.) At the end, also mention you’ll be at the sponsoring store that evening to take questions and sign books. After the school presentation—and some version of checking in/unpacking/eating—you get to the bookstore. As with a school, it pays to arrive a little early. Greet the owner/coordinator, get the lay of the land, browse the shelves if there’s time, meet some customers if there’s time, grab a coffee if available, and get ready for your presentation… As mentioned previously, there are a few different types of signings. Your mileage may vary, of course, but here’s how I broadly categorize them… “Sit & Sign.” This is where the store parks you somewhere (typically near the entrance, or maybe in your genre’s section if it’s a big store) at a table with a stack of your books, and you’re left to try and engage customers as they walk by, hopefully leading to a discussion and maybe even a sale. These are usually not the best experience, and we try to avoid them if there’s another option. You’re engaging with people who aren’t there to see you and likely aren’t even interested in the type of book you’re presenting. There’s no real draw to this sort of signing (unless you have fans/friends/readers in the area who will make the trip to see you) other than the fact that it can lead to signing a fair amount of stock. (Seems like the larger chain stores tend to go for this, so sometimes the stock signing can be significant. When we sign stock we always volunteer to put “signed by author” stickers on the books, because it increases the likelihood that book will sell down the road. Chain stores will have a big roll of these, or you can bring your own to smaller stores.) Also, as there is no actual presentation, it’s harder to give the customers much of value during a sit and sign other than occasionally taking questions one-on-one. “Read & Sign.” This at least offers customers the ‘value’ of hearing you read from your work. (Usually your latest, which they likely haven’t read yet… like a trailer or teaser for your new book.) I put value in quotes because you’re giving them something they can get simply by picking up the book and perusing a chapter. I’m not a huge fan of readings—either as attendee or presenter—but if the audience consists primarily of fan-ish readers (which it usually doesn’t—see below) then this might work well for you and your attendees. At least you typically have the trappings of a presentation—chairs for them and a place in front for you—and there is some interaction between reader and author. And of course you can do a Q&A afterward, which is even more interactive. “Presentation w/Q&A.” This is our favorite, because it has something for everyone. As mentioned, a high percentage of people want to write a book. (And of course, some of them are actually writers, actively writing and/or trying to publish. These people are even more interested in speaking with you.) The details regarding how to decide on the specifics of an author presentation might make a good post unto itself, but a few popular topics include “where writers get ideas,” “the journey to publication,” “making the creative life work,” “the writing process,” and “a peek behind the publishing curtain.” A variation of this is the “In conversation with…” presentation, where someone (often another writer, or perhaps one of the store’s staff) will interview you. Either way, a conversation is almost always better than a one-way delivery. A big key to reaching the audience is knowing who you’re addressing. We sometimes do a quick assessment first (via a show of hands) regarding how many have an interest in writing someday, how many are actively writing, how many have a draft they’re in the process of shopping, how many have no interest in writing but are avid readers, etc. Then we tailor the presentation to them. Another key factor is not making the presentation about you. Ideally, it should focus on them, and give them something that can help them get where they want to go. (There’s nothing more boring than some dude droning on and on about himself and his books, his story, his process, his life, etc.) And of course, the way to make sure you’re giving the attendees what they want is to be as interactive as possible. Sometimes the bulk of the presentation ends up being a lively hour-long Q&A session. (Again, a bunch of concise answers will usually be better than a few long dissertations here. Regardless, we always try to do a “lightning round” near the end where we answer a bunch of questions quickly, because there’s nothing worse than someone sitting through a presentation and not getting a chance to ask their question.) After you’re done you sign books for the attendees, of course, and always be sure to ask the store if they’d like you to sign stock. And… always thank the staff profusely for hosting your visit. This is a mutual-aid thing. Yes, you’re taking the time to present, hopefully bringing people into their store, maybe even new customers. But they’re allowing you to present your work in their establishment, which costs them in terms of time/work/money. You want to leave them feeling good about you and your books, and they want you feeling good about their store. Win-win, right? I can honestly say we’ve met booksellers and school librarians who’ve become lifelong friends through doing events with them. Which shouldn’t be too surprising. After all, we have a shared love of books. Happy touring! “If you build it, they will come” doesn’t necessarily apply to book events. It’s more like “If you build it--and tell them all about it--some of them might come.” Yes, there is the rare store that has such a strong, loyal customer base that you can just show up and there’ll either be a decent sized crowd waiting or they’ll flock to you from around the store once they see an author presenting, but depending on either of those is a very bad bet. And unless you’re hovering near the very tippy-top of the NYT bestseller list, it’s also a mistake to think that your name alone will bring in a crowd. One obvious challenge with a book tour is that you’re not in your hometown. When you do a local book event—assuming you have a new book out and you haven’t done anything local in a while—you can tell all your friends and family and co-workers about it, and get a pretty good turnout from just that. But that doesn’t apply when you’re hundreds or thousands of miles away, in a different state, where you know virtually no one… and very few of them know of you. So, you have to ask (and answer) the question: Why would someone come and see you if they didn’t know you, and/or didn’t know your books? The answer is two-fold: They have to know about the event, and they have to be interested in the event once they learn about it. Let’s take the second part first. People are generally interested in information that can benefit them. I mentioned this last time, but multiple surveys have shown that something like 85% of all adults want to write a book, typically a novel or perhaps a memoir. (And a smaller but still significant number have started writing.) We can provide value to them (beyond talking about our latest book) by stepping outside our specific genre and addressing this broad area of interest directly, as follows… When we were calling stores and the event coordinator/owner/manager would find out we wrote MG & YA, she’d often say “We don’t usually have good luck with kids’ events, and worse with teens.” And we’d say, “We agree completely. We have better luck when we position it as: Two published authors are going to talk about reading and writing and the publishing business.” And we’d promote it that way. And it generally worked. Often we’d have a good turnout with lots of engaged people at the event—asking questions and buying books to get signed—and there wouldn’t be a kid in the room. We’ll talk about presentation specifics more next time, but for now you should come up with a general theme and pitch for your presentation. We call our joint events the “He Said, She Said” presentation and it’s largely based on us riffing back-and-forth on reading, writing, publishing, and living the writing life, and at least half of it is Q&A. (Remember, your goal is to give the attendees something they’ll value, not just find different ways to say “Here’s my book, buy it now!”) And my solo events cover largely the same territory, often focusing on the power of art. Again, with lots of Q&A. So now that you have something that—hopefully—people will be interested in (and that the store’s event coordinator will feel the same about), you want to help get the word out. Sure, you should definitely put your tour schedule all over social media because once in a while someone will show up from seeing that. But really, your strongest move is helping the store let their customers know. Easy things first. Make an electronic poster for each event with all the pertinent date/time/presentation info (as well as graphics of you and your book, of course) and send it to the store. They can print out and place the posters wherever they see fit. Also send them high-res graphics of your book cover & author photo, so they can use them on their website and their social channels and in their email newsletter, etc. When time allows we’ll sometimes send out a turnkey press release—specific to the store, time, and date—for the store to use with their local press outlets and/or social media/newsletter posts. For our big tour we also made a nice overall tour poster which had all the images & info about us and our presentation, with spaces for each store to fill in their specific date and time, then we printed out a hundred of them at 11x17 and sent one to each store on the tour ahead of time. We made a fun (okay, some might say corny) little “tour trailer” video which we sent to all the stores as well as posting on our social accounts. This gives the stores an idea about the vibe of our presentation, and lets them post it on their social accounts to let their customers know a little about the event. Along with this we did a TV interview or two along the route, usually the day of the evening presentation in that market, as well as getting press in some local papers for the same reason. And finally, make sure the store has your book in stock for the event. (Don’t laugh. It seems obvious, but on our very first out-of-state stop on the big tour—in Arizona—the store had my book but not my wife’s, and then in Minnesota the opposite thing happened.) Your publicist can definitely help here, as they’ll get in touch with their sales rep for that region and make sure the store has your books. Another piece of insurance is to contact each store with a quick message a week or so out saying, “We’re on the road headed your way—can’t wait to see you on June seventeenth!” or whatever. (We had one store cancel on us after we’d already started the tour, but luckily we found out ahead of time due to the above and it saved us driving halfway across Mississippi for a non-event.) Okay, the pump has been primed: the store knows, the customers know, and the books are in stock. Next, we’ll wrap up with the day-to-day nuts & bolts of in-store events. Last time we discussed the overall steps in setting up a book tour. Let’s look at some of the important specifics around booking the events as well as scheduling your travel. 1. The Pitch. Believe it or not, not every store you contact will immediately say “Oh my God YES OF COURSE!” when you ask about doing an in-store event. It takes time and effort on the store’s part to put on an event, as well as ordering in your books for it, etc. So the store has to do some quick and dirty ROI calculations to determine if they’re going to have a fighting chance of making a few dollars and/or bringing in some new customers in exchange for their time and effort. All of which boils down to your ability to bring people into the store. Once you let the store know you share the same goals—bringing people into their store—and it sounds like you have a realistic view of how to do that, they’re more likely to want to have you do an event at their store. (More about this in Part III, but a big clue here is that approx. 85% of all adults want to write a book.) 2. Setting the Time and Date. Stores know their local customers and the best times for presentations (and you’ll want to defer to their experience) but much of this is common sense: weekday visits usually happen in the evenings, after dinner but not too late… like 7:00 PM or so. Sometimes I’d be booking a Tuesday in Georgia and the store would say, “We like to do author signings on weekends,” and I’d have to say, “Well, we’re coming through Atlanta on Tuesday… by Saturday we’ll be in St. Louis,” or whatever.* [* But be advised, this is NOT “business hardball.” They’re a bookstore and you’re an author. You both love books, and you’re on the same team. While you certainly don’t want to cool your heels in a hotel room for three or four days waiting for the “perfect presentation slot,” we would occasionally defer for a day under special circumstances. (Ex: Apparently NOTHING happens in Nebraska during a Cornhuskers game, so we had a day off in a hotel in Omaha on a Saturday, which is usually a prime day.) But overall the stores were almost universally accommodating to our schedule… we managed to present six-plus days a week for four months during our biggest tour.] 3. School Visits. As opposed to in-store events (which are free), school presentations typically include an honorarium. (See this post on some issues associated with doing free school visits.) But while we were on book tour, when scheduling allowed we would occasionally tell the store that we’d donate one joint presentation—free—to a local school of their choosing, during the day of the store event. There were several reasons this made sense…

4. Booking Lodging. We booked virtually everything online in advance. At first we booked a few weeks ahead, as we traveled, but after a couple of close calls we started booking further in advance, and by the time we did the second leg of the tour we had everything locked down before we even left the house. Logistics matter here, and you can optimize your hotel time with a few little tips regarding how you juggle your presentations and lodging: We booked in one of three general configurations: the “sign-and-sleep,” the “hit-and-run,” and the “two-fer.” The sign-and-sleep is your basic “Do the evening event, go to your hotel and sleep, then get up and drive to the next stop” routine. And it works fine, especially when you have quite a distance between stops. The downside is you don’t get the best bang for the buck, hotel-wise… you’re either checking in during the afternoon then grabbing dinner and doing the event, or—depending on how far you had to drive—arriving in town then eating, then doing the event, then checking in and hitting the hay before getting up and driving on. If we didn’t have a super long drive to the next stop and/or if the event was reasonably early in the evening, we’d do a hit-and-run, which meant instead of sleeping in the event town we’d do the signing then immediately drive to the next stop and check in… where we’d usually have a two-fer. (Two nights in the same place.) That way we’d wake up and have the whole morning (or day, if no daytime event) to hang out at the hotel, go for a run or swim or sightsee, and get in some serious writing time down in the lobby with coffee and snacks. Then after the evening event we could just go back to the room and hang. You get more “hotel time” for the same outlay, and of course you only have to load-in, unpack, pack up, and load back out once instead of twice. We did this whenever we could, and it always felt like a luxury when we could have a day to hang out or sightsee without having to pack up and drive. (We presented six or seven days a week, so any little break was welcome!) Regarding rooms, our basic priority list when booking was:

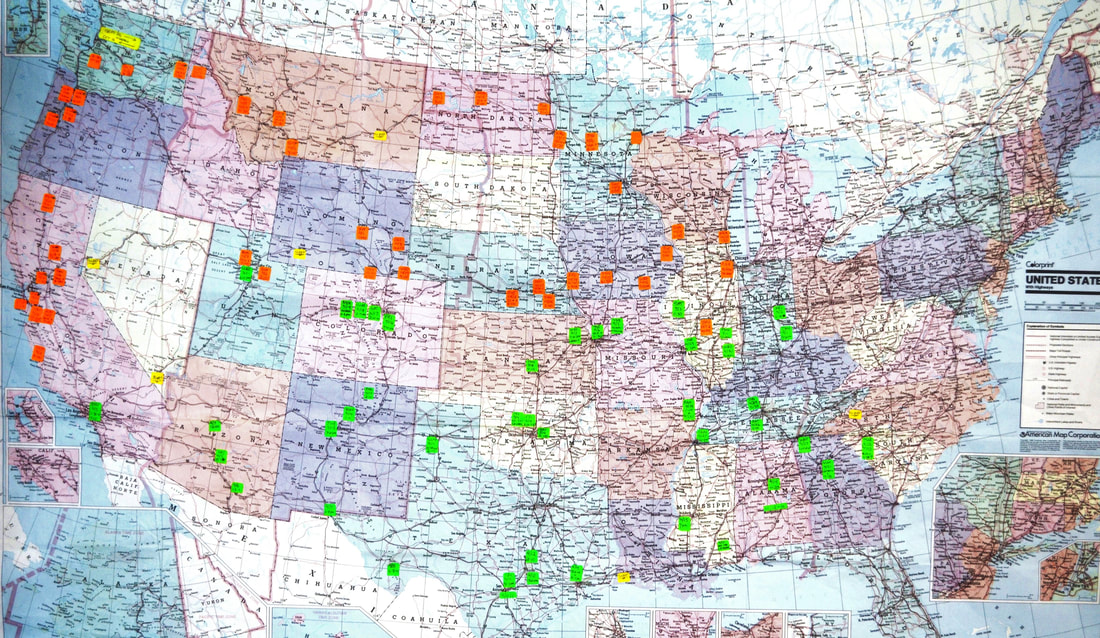

Next time in Part III we’ll discuss making sure you have people (and books!) in the store during your presentation. See you there! We’ve gone on three different book tours within the past year. First for my wife’s newest book (The Peach Rebellion) last May, then for my latest (The 9:09 Project) in Nov/Dec. And since both our books published within 6 months of each other (at different imprints of the same umbrella house), we couldn’t pass up the opportunity to go on a “He Said/She Said—Part II*” joint book tour, from which we just returned a couple of weeks ago as I write this. [*To recap, the original “He Said/She Said” tour was a four-month national book tour covering well over 100 venues. Probably the biggest U.S. book tour of that year. See here for more on it.] The original post covered the “why” of touring, from a philosophical viewpoint, but I’ve gotten questions about the logistics (aka the nuts & bolts—the who, what, when, where, and how) of setting up and executing a book tour. When I was younger I spent a fair amount of time on the road playing in a few different bands, and many of the logistical lessons I learned on the road still translate well today (and certainly came in handy when we booked that big, crazy tour half a dozen years ago). So let’s dive in… 1. When. The first decision—before you even figure out where you’re going and which stores to visit, is when to tour. Obviously, the best time is when you have a new book out. Throughout the life of most books, the briskest selling period will usually be in the months after release, and you (as well as the Event Coordinators at the stores you’re visiting) will want to capitalize on that. However, if there’s no new release but you have a backlist that sells well, this can also work. Or you could tour with a friend who writes in the same genre who happens to have a book coming out. (Think about how big musical acts tour – their either have a new record out, or they do a “greatest hits” tour, or they do a “package” tour with other like-minded bands who have a similar fan base.) Then decide how long you want to be out. Realistically, you might average one store an evening, with perhaps one non-store presentation (school, conference, festival, etc.) during the day. (Weekends are different—you can sometimes do stores during the day and evening.) So if you want to present at a minimum of a dozen stores, for example, plan on a couple of weeks. Once you know how long you can be on tour and the rough number of stores you’d like to visit, you can start planning your route. 2. Where. At its most basic, a workable plan looks like this: Pick an efficient route that goes through a number of target-rich environments. (IOW, a major interstate that passes through a bunch of cities and towns that have bookstores.) A loop route is generally better than an out-and-back because you don’t want to hit stores near other stores you’re covering (the stores don’t like it, and you’re drawing from the same well of customers twice) so a circular route gives you twice as much “fresh territory.” (Our overall rule was stores should be at least 20 miles apart, and ideally further. Big cities are an exception, because two stores ten miles apart can have totally different customer bases. This will come up in your conversations with the Event Coordinators at the stores.) A few factors will help determine the route specifics: where you live, any special places you may have as a goal destination, and desired daily mileage. You can occasionally bang out 500 miles or more in a day when you have to get across a “book desert” to get to another locale, but that’ll wear you out quickly and takes all the fun away. We try not to schedule more than 200 miles for most “normal” tour days. That’s only three or four hours of luxurious sight-seeing per day—broken up by meal stops, etc.—which makes for an easy cruise. (Plus, the goal isn’t to cover the most miles, it’s to visit the most stores, so venues closer together makes for a more efficient tour.) 3. Who. Once you know the basic route, it’s time to look for likely venues along the route. Good sources of info for this: The American Booksellers Association website (click their Find a Bookstore tab, then enter the city you’re currently searching); entering “bookstore” into the Nearby tab on Google Maps when you’re mapping a given location; and word-of-mouth, either from fellow authors, local booksellers (indie stores know each other), or asking for recommendations on social media. When hunting for likely prospects, you’ll have your own personal criteria. We were looking for indie bookstores which had good connections to their local community, with bonus points for hosting regular book clubs and/or writers’ groups, having a coffee bar, and having a store dog or cat. Number of books in stock might also be a consideration for you… all bookstores are wonderful in their own way, but a store with 5000 books is less likely to carry your titles than one with 50,000 books. Not that this should be a Boolean consideration, however—some of our best (and most successful) visits were at smaller stores. At first, you’re looking for more initial prospects than you’ll need. (Take the total number of days you’re going to be out and multiply by two or three—ideally two or more in each target city on the route--for reasons we’ll see shortly.) We’ll talk more about the selection process when we get to the “how.” 4. What. This may be the easiest part—deciding what your presentation will consist of. Broadly, there are three categories of signings: the “Sit and Sign,” the “Read and Sign,” and the “Present and Q&A.” We’ll do a deeper dive into these in Part IV, but the critical task here is to come up with a general idea of a presentation that works for you, your books, your audience, and the bookstores you’re visiting. The reason you need to come up with a rough idea now (instead of months down the road when you’ll actually be doing it) is that you have to sell it to the event coordinators at your target venues (more on this in Part II) and if they don’t think you’ll have something of interest to their customers, it’s going to be a much harder sell. My overall advice here is something I’ve reiterated before: the worst way to get people interested in your work is to drone on about it. OTOH, if you come off as interesting or informative, they’ll naturally be inclined to think your book may be likewise, and may check it out. (TL;DR: Do not shout “Buy my book!” at potential readers. It’s bad form… and it never works.) You don’t need to decide on every detail at this point, just enough to be able to say to the event coordinator, “I have a presentation that covers X, Y, and Z, and I take questions from the attendees. Then I sign for everyone who wants a book, and I’m happy to sign whatever stock you have.” 5. How. Now that we know what we want to do, let’s step through the nuts & bolts of the preliminary actions. Be aware that for a significant tour you’ll want to start this process well in advance of the projected tour dates. Like several months. 1. Buy a big-ass map covering your potential tour area and put it on the wall in your workspace. (We call ours the “war room map,” because that’s what it looks like in the middle of booking a tour.) Get small colored stickers in various colors. a. We used different stickers for “initial,” “provisional,” and “confirmed.” b. Don’t highlight your route, because it may (will) change. 2. Start building documents to track all the information discussed below. Use whatever method works best for you, but we ended up with an overall plan and a page for each day of the tour with all pertinent info. (Venue, location, time/date, name of contact, etc.) My wife is brilliant at building informative spreadsheets for this (lucky me!). 3. For each city on your route, look at the list of candidates you compiled in #3 (Who), above, and order them in terms of your preference. 4. Make initial contact with your first choice for each given date/location. (You’re contacting a business with multiple employees, so phone is the best for this.) Introduce yourself, briefly explain you’re setting up tour dates, and obtain/verify Event Coordinator name & contact info (which is the whole purpose of this call). a. Place an “initial contact” colored sticker at that location. b. Go to the next target location and do the same. Etc… 5. Contact the Event Coordinator to discuss possible events. (This may happen during the above call, but will usually require a follow-up call or email.) Explain the tour basics and the rough timeframe you’ll be in their area, and get provisional approval. Explain that you’ll circle back to confirm a specific time/date when schedule is finalized. a. If they pass, go on to your 2nd choice for that location and do the above. 6. Do this for every venue on your route, at every likely city. a. Again, keep spacing in mind. You don’t want two stores in the same market, but you also don’t want big gaps of several hundred miles if possible. 7. Go back to your first venue and confirm a logical start date/time that works for you and the store. This is your “anchor”--everything will stem from this date. Replace the “provisional” sticker at that location to a “confirmed” one. a. Gen up and send a ‘confirmation document’ to the event coordinator with all pertinent information. 8. Go to the next store on your route that provisionally approved a visit and book them for the next day. 9. Continue the above, through the rest of your route. Realistically, you’ll still be getting initial approvals for the end of the tour while you’re starting to finalize the early stops. That’s fine, because by that point you can say, “We’re scheduled to come through your area during the middle of the first week of August, so can we pencil in the 3rd or 4th, and we’ll confirm with details in a couple of weeks?” In Part II we’ll cover some of the details around the scheduling of the signings, booking school visits along the way, and the logistics of booking rooms. Happy tour planning!

[Haha! I lied to you, as writers do. This is not a tutorial on how to write a query. The floor of the internet is absolutely littered with them. This is a little story about how to successfully land an agent who’s a good fit for you and your work. Which actually has very little to do with your query.] You are a produce seller, with a stall at the farmer’s market. And a sign, describing your wares. You don’t have a wide variety of products. Probably one. Maybe two. Rarely three. In other words it’s all about quality, not quantity. An agent is a shopper, going to market with a list. And they also have some sort of sign… maybe a fluorescent sandwich board, maybe just some words scrawled on the back of their t-shirt with a faded purple sharpie. But they all have a sign somewhere, if you look for it. You can read—find it and read it. Let’s assume they’re looking for peaches. Specifically, peaches that remind them of a warm summer’s evening when they were a kid, hanging on the street corner with other kids and eating farm-fresh peaches with the juice running down their chin. Those kinds of peaches. Not canned peaches drowning in high fructose corn syrup. First off, if your sign says “Strawberries!” they’re likely to pass on by, even if your strawberries are exceptional. (Especially if they’re carrying a sign that says “No berries!” and you still try to talk them into your strawberries. Odds of success here are rapidly approaching zero, right?) However, if your stall has a sign in front saying “Peaches for sale,” they’re very likely to stop and at least take a look. If your sign says “Fresh peaches for sale,” I suppose they might be even more inclined to stop, and if it says “Ripe, juicy, farm-fresh peaches for sale,” they’re almost certainly going to stop. But peaches are expensive and they only have room for a few of them at the moment, so guess what? They aren’t going to think, “That’s a really well-written sign—I’m just going to buy those peaches.” Are you kidding? They’re going to try a sample. And at that point, everything depends on that sample. Everything. You can tell them, “These are the best, juiciest, freshest peaches in the whole market,” and it won’t make one damn bit of difference if they take a bite and disagree. You can talk about your peach-growing degree or the fact that you won the peach pie contest in eighth grade or that all your friends absolutely love your peaches and… Yup. They don’t care. If the sample is less than scrumptious in their opinion, adiós. But if your little stall has a simple sign that says “Peaches,” and you say, “I see you’re looking for fresh peaches… here’s a sample of mine” and they take a bite and the juice runs down their chin and they’re suddenly transported back to being twelve years old on the street corner on a warm August night, guess what? They’re going to buy a bag and see if the rest are the same. (They will be, if you take your peach-growing seriously.) And once they realize your sweet little sample was telling the truth about your peaches, they’re going to want to be in business with you, helping you sell your peaches all over the world. Happy farming! We’ve all heard the fable of the dry branch breaking while the supple limb flexes and comes back stronger than ever. Nowhere is this more apt than in working with publishers and their creative staff. Recently I heard someone talking to his friends about his newly-finished book manuscript. Someone asked, “So when’s it coming out?” and the writer replied, “As soon as I find a publisher that won’t make me change anything!” I was there as a friend-of-a-friend so I didn’t say a word, but what I thought was, So… never, then? Because that’s what publishers do! I don’t mean they alter the meaning of your project or make changes without your approval or anything even remotely nefarious. What they do do is ensure the books they publish are the best versions of those books possible, in the expert opinion of their creative staff (editors, editorial directors, art directors, copy editors, designers, editorial assistants, etc.) who—collectively speaking—have vast amounts of experience in publishing. They earn this right via the simple fact that they’re paying for the production of your book, from your advance to the editor’s salary to the physical printing of the books (to say nothing of the publicity, sales, marketing, and distribution of said books to various venues all over the world… all of which contribute to your bottom line). And beyond that, they’re generally pretty damn good at what they do. (Maybe better than you… definitely better than I.) And they generally know what works in any given market… again, maybe even better than we do. Because of the above, they will actually offer editorial suggestions regarding manuscripts they plan on publishing. And if it becomes clear that you—as the author of said manuscript—aren’t amenable to considering feedback regarding your precious words, you suddenly become much less interesting to the editor in question. On the flip side, if they get the vibe that you’re a talented writer who also plays well with others, that’s a plus. Virtually every story of publishing success I know of involves taking (or at least seriously considering) editorial input at some point. My very first professionally published piece began as a letter to the editor of a magazine. But the more I worked on it, the more it started to look like an article (at least in my naïve opinion at the time). So I went ahead and wrote the entire piece (around 3000 words, IIRC), complete with charts and graphs and photographs. (Which I developed in our little homemade darkroom, indicating what century this was.) Then I bundled up the whole thing and sent it off to the editor without a word of warning. (Query letter…? What’s that?) His response upon receipt of my bundle of literary brilliance? “Sorry, but we’ve already done something like this.” Shit. “But…” he suggested, “how about writing an article about this, instead?” And the this he referred to was something I didn’t have a lot of interest in, to be honest. But hey, this door into publishing—even if it was the wrong door, leading somewhere I wasn’t really interested in going—was open. If only a crack. And it was the first door I’d seen up until then that wasn’t bolted tight. So I took his suggestion and wrote the piece (which he bought and published) and that was the beginning of my nonfiction career, leading to two hundred articles in various national publications as well as a couple of nonfiction books. My first fiction sale went something like this: I submitted a science fiction story to the editor of my favorite SF magazine. (A breathtakingly brilliant story that was absolute perfection in every way, I might add.) His response was basically, “It’s an okay story, but we don’t need to see the protagonist break in and steal his boss’s prize fish. It’s obvious. Just have him leave, and then return with the fish.” Man, I hated that suggestion. Because I loved the fish stealing scene—so clever, so funny, so… superfluous. Yeah, once I removed it (something I never would have done on my own) I saw he was right. So I sent him the revised story, and he bought it and published it. Which was awesome. But even better, I learned an invaluable lesson—just because a scene is “good” (or well-written or funny or clever or whatever adjective strokes your writerly ego) doesn’t mean it helps the story. And the secondary lesson here was that this insight didn’t come from a writer, but an editor. Because that’s what editors do--they make stories better. Not by re-writing them, but by making suggestions to the writer as to how they might re-write them. (Understanding this difference is crucial, lest you fall prey to the goofy-yet-popular “Publishers will totally change your shit and publish it without your approval” myth.) My wife’s first book deal came about when an editor read her manuscript and returned it with a note on the order of, “I like the voice but it’s way too long for the genre. If you cut it in half, I’ll look at it again.” A lot of writers would have thought, NFW am I ripping this thing apart for a major structural rewrite just because one person might ‘look at it again’…! That’s a ton of work with no commitment on the editor’s part, and my wife obviously thought the book was good as-is or she wouldn’t have shopped it. (No agent at this point.) Yet the door—while not exactly open—was at least unlocked. For now. (That’s another thing about rejections-with-suggestions: they come with an expiration date, which is exactly as long as the editor’s memory of her good feelings about your manuscript. Different for each editor, but generally weeks or months and not years.) So (with my loving support and encouragement… most of which consisted of me saying, Are you freaking crazy? Of course you should do this!) my wife buckled down and did the hard work of making the book significantly shorter while keeping the stuff that made it unique and wonderful in the first place. The editor eventually bought it—which started my wife’s career in children’s literature—and they currently have thirty-plus books together… and counting. My first book deal (nonfiction) was also based on suggestions, but in this case it was the writer giving suggestions on the editing rather than the other way around. I’d written a fairly lengthy series of how-to articles for a magazine, and when the series was concluded my editor floated the idea of bundling them up into a book, basically re-printing the articles as they’d originally appeared in the pages of the magazine. I’d had similar thoughts, but I didn’t want it to be just a ‘collection of articles,’ so I suggested I write additional material to bridge each section and gen up additional photos and drawings (as well as change the 3-column magazine format of the text to a more “bookish” 2-column layout) which the editor was flexible enough to agree to. The end result was a coherent book the editor and I were both proud of—it became one of the better selling books the publisher had at that time—and I can’t help but think this might not have been the case had we just put out a quickie compilation. With my first published book-length fiction (a YA novel), there was some editorial back-and-forth between me and the editor before I even got a contract. I recently heard someone opine that you should never do any revisions without a contract (and if your last name is Rowling or King, I might agree) but my thinking is if an established editor at a reputable house is willing to work with me on my manuscript, then I’m goofy not to. Her suggestions were very good—typically more about what to trim than what to write—and I took at least 80% of them. And I ended up with a contract and an advance and an agent and a book I’m proud of. None of which would have happened had I put my foot down in a show of authorial inflexibility. And finally, with the novel I recently sold (actually, which my amazing agent recently sold, to a Big Five imprint), the editor had some questions before she made an offer. She let it be known that she was interested in the manuscript—loved the main character and his voice—but she needed answers first regarding how I might address certain things. I felt she was basically saying, "This is roughly what I think it needs. If you aren't up for doing the work, let me know before we tie the knot." And I totally understood that viewpoint, and I really appreciated her forthrightness. (See this post on how “a willingness to revise” is one of the main things an editor looks for in an author.) Then I proceeded to reply to her with a couple thousand words on how I might address her comments. And, well, here we are—the book pubs this fall and I couldn’t be more excited. And to be honest, I think my general willingness to roll up my sleeves and work with her was as germane to selling the manuscript as any specific revision ideas I came up with. And… now that that manuscript is pretty well buttoned up, we’ve had a conversation about next steps. I said I had ideas in sub-genres A, B, and C, and she said she was more interested in books that fell under B than A or C. Fair enough. So I sent some pages of an idea that came under B, and she let me know what she liked and what she thought needed some tweaks. Again, I’m free to do what I want, but if I want to continue to work with her, the smart move would be to work in an area in which she’s interested and listen to her feedback. So that’s what I’m doing. Begin to see a pattern here? So… if you need a publisher that will put out exactly what you write, word-for-word, without suggesting any editorial changes, that’s easy. You just have the wrong P-word. You’re not looking for a publisher, you’re looking for a printer. There are a ton of them who’ll be happy to take your money and print up your draft exactly as-written. And there are lots of sites where you can “just press publish” and your words will be magically available to whoever wants to read them, exactly as you drafted them. And all of that’s perfectly fine. But if you want to successfully work with a publisher—one who will pay you, as well as pay for the production, printing, publicity, sales, and marketing of your book—then a little creative give-and-take can go a long way. And will very likely make your book even stronger than it would have been on its own. After all, you and the publisher want the same things—for your book to be the best version of your story, and for it to find success, both artistically and commercially. Don’t be so brittle you break. Sometimes there’s more strength in being agile. Happy flexing!