|

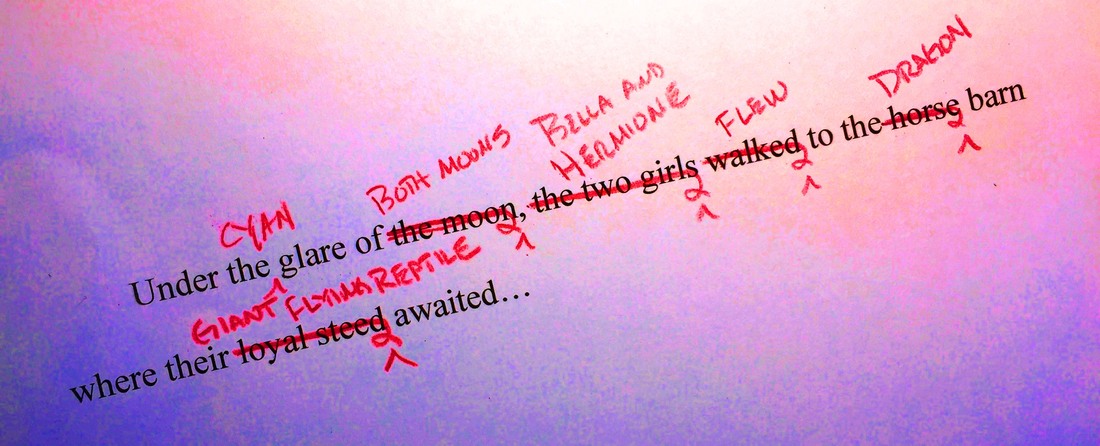

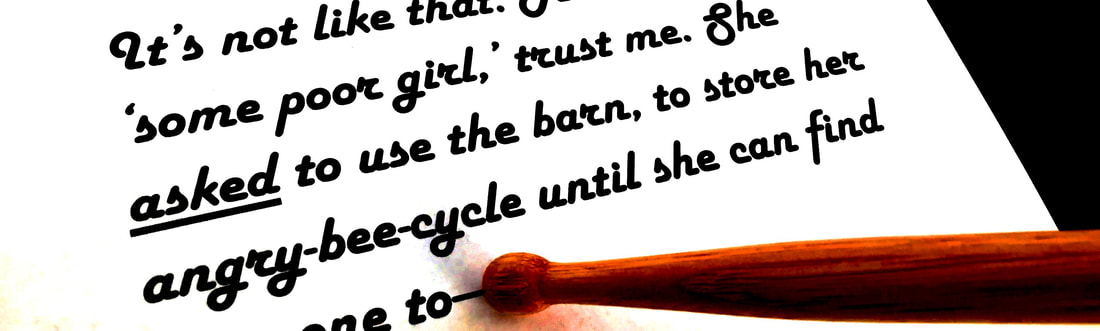

One of the many things copyeditors do is check the grammar and usage of your character’s dialog, making sure everything is consistent and correct. And when they make a correction to something (specifically, something said by a character or something in interior monologue—which in a 1st person novel is virtually the whole manuscript) and the correction doesn’t reflect what I want the voice to say, I write “Stet, for voice*” in the comments, and they get it. [*Stet is a common CE comment—it’s Latin for ‘Let it stand.’ And ‘for voice’ means we’re leaving this as-is because it represents a character’s authentic voice.] Same with the ubiquitous “friend w/English degree” or your MFA neighbor or whoever you have read your manuscript to make sure everything is “correct”… whatever that means. Except there’s a chance (a good chance, in my experience) they may not fully get the ‘stet, for voice’ concept, and in the desire to make sure everything’s “legal” the aspiring author may likely go along with the ad-hoc recommendations. Which can be dangerous… because correct is not always best. Especially in fiction. Strunk & White-style grammar may not be the same as the way your specific character—with their background, age, and education—might really talk. And having your character speak with perfect, college-professor-level diction is probably going to grab the reader’s attention… in the worst way. Because it doesn’t ring true in most cases. And ‘ringing true’ is a necessity when you want readers to relate to your character as though he/she were a real person. (And you definitely want this, if you want your book to resonate with readers.) Dialog can be tricky. You generally don’t want to exactly replicate real verbal exchanges—with all the ums and uhs and ahhs and you-knows and incomplete and/or incorrectly structured sentences and run-on verbiage, etc. BUT… you also don’t want your characters to speak perfectly, as though they’d written out everything they were going to say and then did a deep edit on every sentence, making it “perfect” before saying it in what is supposedly realistic, unrehearsed, actual, you know, conversation. (Let alone having your characters pass on information to the reader disguised as dialog which the other character likely already knows. This type of “As you know, Bob” exchange is clunky in the extreme and there are so many better ways to convey the information, including just having a snippet of dialog and then having the character tell us via internal monologue some of the non-stated information. Or suppress the need to explain everything and let the reader figure it out via context down the road.) There’s a balance. We want our dialog to feel like real off-the-cuff human speech while not totally replicating the overly-padded content of actual dialog… and we want the dialog to convey something important to the story and help it move forward, whether that’s information or character development (or, ideally, both). But what it very likely won’t be is grammatically perfect. (Keeping in mind the great Elmore Leonard’s dictum: “Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly,” lest we error on the side of clunky, corny, or outright stereotyping.) And while the concept of “Stet, for voice” obviously applies to dialog in the micro, it also—in the macro—applies to your writing in general. We’ve discussed the concept of “voice” before (here) but it’s important to understand that the book’s voice—whether the character’s or the narrator’s, if applicable—might be the single quality that most affects the reader’s pleasure (or lack thereof) on a page-by-page basis. Yes, the plot takes shape as we move through the book, but the voice is right there in every paragraph, every sentence, every word we read. And if the voice doesn’t ring true, if it doesn’t compel us to read on, if it doesn’t make us connect with the character on an emotional level, then the plot probably won’t matter… simply because the reader may not make it to the end. But if the voice grabs us and pulls us into the story and makes us care about the character and what happens to them, we’ll probably follow it no matter what. SO… don’t give up what makes your book unique (your character with their own specific voice) simply because they don’t always utter the King’s English. This doesn’t mean anything goes… that you can have your character speak in a wildly inconsistent manner, that the character’s voice can be a total mismatch for their personality, that you can sling slang all over the page and not have it throw readers out of the story. You still need to be in charge of the character’s voice, and the decisions you make regarding it need to be made with an eye toward the overall effect on the reader. (Developing this sensibility to where you apply it almost unconsciously is a perfect example of the level of craft that comes from practice, and knowing when you’ve overdone it—and are willing to revise it back toward the norm—is yet another level of experiential aptitude. As is a willingness to listen to cognizant feedback about these things… from your editor or elsewhere.) Ideally, your character’s voice—and how you choose to portray it—is another tool for your creativity to express itself when it comes to crafting something that’ll have a compelling emotional impact on the reader. A powerful tool. Don’t give up this power in the name of perfection.

0 Comments