|

Writing a novel is sitting down and telling yourself a story you really need to hear. It’s that simple. Not to be conflated with ‘easy’ - two different things entirely. But yes, simple. Simple because it takes a lot of the “industry research” aspect out of what should be a personal, creative, emotion-driven decision. Instead of trying to discern what’s currently ‘hot’—and then performing some sort of magical thinking to determine what’s still going to be hot in three or four years—you simply use the north star of: What do I really want to write next? And then do that. I’ve made up a lot of bedtime stories (like, a thousand or so, as discussed here). Writing a novel is a similar process only at a much bigger and more complex scale, over a much longer period of time. But the commonality is that the emotional driver as you go through the process—whether a 10-minute story or a 500 page novel—is basically: If I were in the middle of this what would I want the next move to be, as an engaged reader? As implied in the opening line, the real goal is to write in such a way that you—as the author—are totally wrapped up in the story, heart and soul. I firmly believe there are massive benefits to this level of emotional engagement for the writer. When it’s going well, writing a novel feels like very much like reading a really good book. When you’re really immersed in a great book, you think about it when you’re away from it and you can’t wait to get back to it because you can’t wait to see what happens next. It’s the “Can’t wait to see what happens next!” part that drives the writing of good fiction. In a sense, you really are telling yourself a story… a story in which you’re totally immersed. And it’s the “Tell yourself a story” that I think might just be the key to the whole thing. I see a fair amount of people who seem to be driven by the belief that they “need to write something the market wants.” As we’ve discussed before, trying to follow a trend in publishing is problematic in the extreme, for temporal reasons among others*. [*TL;DR: The books currently splashed across endcaps at B&N were acquired two years ago. It’ll take you a year to write/revise/polish something similar; months to query; more months on sub to get it acquired; 18 to 24 months from acquisition to pub day. Do the math.] BUT… if you instead tell yourself a story that you truly want & need to hear, you’ll be fully invested… not just plot-wise, but emotionally… to the point where the characters become real and you actually, deeply care about them… which is the only way to get agents and editors and readers to care about them… which, ultimately, is the only way to get your book splashed across those coveted endcaps. It's like perusing the stacks at your favorite indie bookshop, thinking, Hmm… what am I craving? What am I in the mood for? What do I really want to read? Except you’re browsing your own imagination, and you’re transposing the object of that sentence from read to write. But artistically, the process is almost identical. You’re window shopping in your mind’s eye. And you shouldn’t be concerned with buying what’s on sale—you should buy what you really want! Happy shopping!

2 Comments

The Pages As we discussed last time, the sole purpose of a query letter is to get the agent (or editor) to read your pages. And once they’ve moved on to your sample, their decision on whether or not to move forward will depend solely on their perception of said pages*. [*Assuming you’re a debut novelist—things change a little when you have a track record, and the process is different with nonfiction.] And to that point, at a recent conference three agents on a panel were asked, “How long does it typically take you to determine if you’re going to pass on a manuscript?” The answers were, respectively, “around one paragraph,” “maybe two paragraphs,” and “usually one page.” All of which might lead one to ask, “How can they even tell what the book’s about by reading the first page?” And the answer, of course, is that they can’t. They use this methodology because to them, the overall plot* is immaterial if the manuscript doesn’t also have (1) an interesting/engaging/compelling voice which makes a connection with the reader, and (2) sentence-level writing craft that makes the story feel like real, lived experience to the reader. (IOW, the top priority is emotional connection, requiring both voice and craft.) [*Don’t misread me--plot is super important, and if the writing and voice are both up to snuff they will of course read the whole thing – multiple times - and gain a deeper understanding of the scaffold behind the story. But #1 and #2, above, have to be there before they consider #3.] So… this gives us some good guidelines about what should and should not be in our opening pages (and in the rest of our pages, for the most part). Some thoughts on how to implement this… *Stay in scene. (This is the overall thing to keep in mind, and the next five or six bullets will augment this concept.) Try to have your character doing something. It doesn’t need to be running from a monster. It could be having a conversation with her best friend about their weekend plans. But we need to see it, not be told about it in a summary way… which means it’s best if she isn’t sitting by herself ruminating for ten pages. Related to that… *Voice and Pace are paramount. To that end… *Avoid over-explaining. Many newer writers feel the reader needs to know all the backstory before moving forward, when the exact opposite is true*. Instead, plant “curiosity seeds”… those little things that make the reader think, “Now, what does that mean?” and compels them to keep reading. [*Andrew Karre, executive editor at Dutton/Penguin, says: “Valuing information over intrigue, especially in first chapters, is a rookie mistake. Where the beginnings of novels are concerned, I value intrigue over information, feeling over knowing, magical confusion over mundane clarity.”] *Avoid flashbacks in the early pages. We’ve discussed the nuances of flashbacks earlier, as well as mentioning their danger, especially in your early pages. (In brief, if the flashback is for explain-y reasons, probably better to let the info come about organically - in small bites - instead. Or put the flashback later, when the reader is more familiar with the character and setting.) *Avoid head-hopping early on. We’ve talked before about what I call the ‘cost of transition.’ Much like with flashbacks, it costs in terms of reader engagement every time you ask them to transition to another time or place or into a different character’s point-of-view. Remember--you know your character and their entire story, but at this point in the book the reader is still trying to get to know them… so give them a chance to do that before you suddenly change things. *Avoid excess exposition. I hate saying ‘Show, don’t tell’ because it’s too reductive, but a significant part of ‘staying in scene’ is that we feel like we’re there with the character, going through whatever she’s going through. And telling us all about the situation (i.e. excess exposition) is so much less immediate than experiencing it with the character. Most of what you want to tell us should be available through context, or you can feed it to us in small bites later. *And especially, avoid expository dialog. Giving the reader info through dialog (often via having two characters talk about something they both know… or should know) throws the reader out of the story. (“As you know, Bob, our estranged father was a paleontologist who was trying to bring back pterodactyls for personal transportation…”) *Avoid clunky clichés. Unless you’re writing a parody of a bad 80’s romance novel, avoid having your character look in the mirror and tell us what she sees as a way of describing herself. Avoid beginning with your character waking up after a questionable night with the sunlight “stabbing through her eyelids like the talons of a million flaming vultures.” (Avoid starting your novel with your character waking up, period, unless necessary.) *Avoid purposely using fancy “writerly” writing to try and make an impression on the agent/editor. It’ll make an impression, but probably the wrong one. It’s generally less transparent and less immediate—making the reader feel further from the scene—than using declarative sentences. As Elmore Leonard said, If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it. *Same with blocky conversations. Harlan Ellison once looked at a manuscript for all of two seconds and said, “The dialog’s off.” He pointed to a sample page—which had large, solid blocks of one person speaking and then another person replying—and said, “That’s not how people talk. They don’t make long speeches to each other, it’s a back-and-forth thing, with plenty of white space.” If you want the agent or editor to gobble up your early pages, I’d advise leaving the lengthy pontificating for the op/ed pieces. *Transparency is your friend. Just as with overusing metaphors and similes, using a lot of adjectives and adverbs will generally weaken the sentence-level writing. The whole goal is to not throw the reader out of the scene, and anything that distances the reader from the character and the scene is contrary to that goal. *Beware the wild attribution. Seriously. There are very few instances where the best/most transparent choice of attribution is something other than “said*.” There is nothing that will throw someone out of a story quicker than having a character “exclaim” or “utter” or—in a double sin—“utter angrily.” Yes, there are cases where we don’t want to use the same word twice in close proximity, but “said” is transparent to the reader, almost like a period at the end of a sentence. [*Elmore Leonard again: Never use a verb other than "said" to carry dialogue, and never use an adverb to modify the verb "said"…he admonished gravely.] *Don’t over attribute. There are some mechanics which will help with this:

If you take care of these mechanics, your dialog will read better, the pace will feel brighter, and the exchange will (hopefully) feel real and not throw the reader out of the story. Speaking of mechanics… *Pay attention to nuts and bolts. A typo on pg. 3 isn’t going to sink you, but three typos and a grammatical blunder on the first page very well may. You want them to feel like they’re in the confident hands of someone who understands the craft. This doesn’t mean you have to have perfect SPG (Spelling, Punctuation, Grammar), but you have to know when you’re solid and when you’re on shaky ground, and if you’re unsure you have to get it checked by someone who does know. *Follow the submission rules. If they ask for the first five pages, don’t give them nine pages because “that’s where the scene ends.” If they ask for the first ten pages, don’t give them pages 50 through 60 because you think that’s the strongest chapter. But use common sense. If you think your epilog is too slow, start your sample with pg. 1 of chapter 1. (No worries—if she asks for a full, send her the whole thing. She won’t ding you for it. But maybe that’s a sign the epilog could be cut after all…?) I’d recommend having samples of common request lengths (5/10/20) all polished and edited for maximum value at their given length, lined up and ready to go. Remember, the goal of the early pages isn’t to get them (agent/editor) to understand your entire book (or your character’s background or the details of your worldbuilding). It’s to get them hooked on your character, her voice, and her journey—all via the quality of your sentence-level writing—to the point where they’re dying to read further. Just as the singular task of the query is to get them to turn to your pages, the job of your sample pages is to NOT give them a reason to put it down, but to compel them to want more. Happy submitting! The query. It’s important. But… No one ever got a book deal from a query. Seriously. This shouldn’t be a controversial statement but with today’s focus on “the query” as the be-all and end-all of becoming published, it might take a few by surprise. But I stand by it—no agent or editor ever read a query letter and said, “This is such a great letter! Let’s send them a contract, this minute!” So as a follow-up to our previous post I thought it might be worth discussing the concept of: What does a query actually do? There is one primary job, but first let’s break it into a few sub-tasks… 1. It lets them know the meta-data around your book, so they can quickly assess if they even want to consider it. If an agent’s MSWL clearly states “No kidlit” and your query starts with “My middle-grade novel is…” they’ll delete it on the spot and move on to someone who can follow basic instructions. 2. It lets them know if—at a minimum—you possess the basic writing skills to construct a common-sense, readable, compelling cover letter. (As one newer agent recently said, “If you can write a coherent query letter it automatically puts you ahead of 90% of the other querying writers.” And as agent Erik Hane [from the ‘Print Run’ podcast] has said more than once, “A query letter is just a business email.”) Because if you can’t, there’s no point in looking at your pages even if all the meta-data is on point, right? 3. Besides giving them the pitch for your manuscript, it lets them know if you know the important highlights of your book… the character, the setup, the central conflict, and the stakes. If you can clearly delineate these things to them, it gives them reassurance you know something about crafting fiction, and… 4. It lets them know if what you’re offering is in their wheelhouse. If they’re interested in book club fiction about family drama and your pitch starts with “My 80,000 word upmarket women’s novel follows our thirty-year old protagonist who left home the day she graduated from high school but now has to return to her wildly dysfunctional family because she just got word that…”, then the agent is likely to think: This sounds like my jam, and turn to your pages. With the above in mind, there are a few simple ways to concoct your query. A common one is some version of the “Hook, Book, Cook” format, which basically goes as follows…

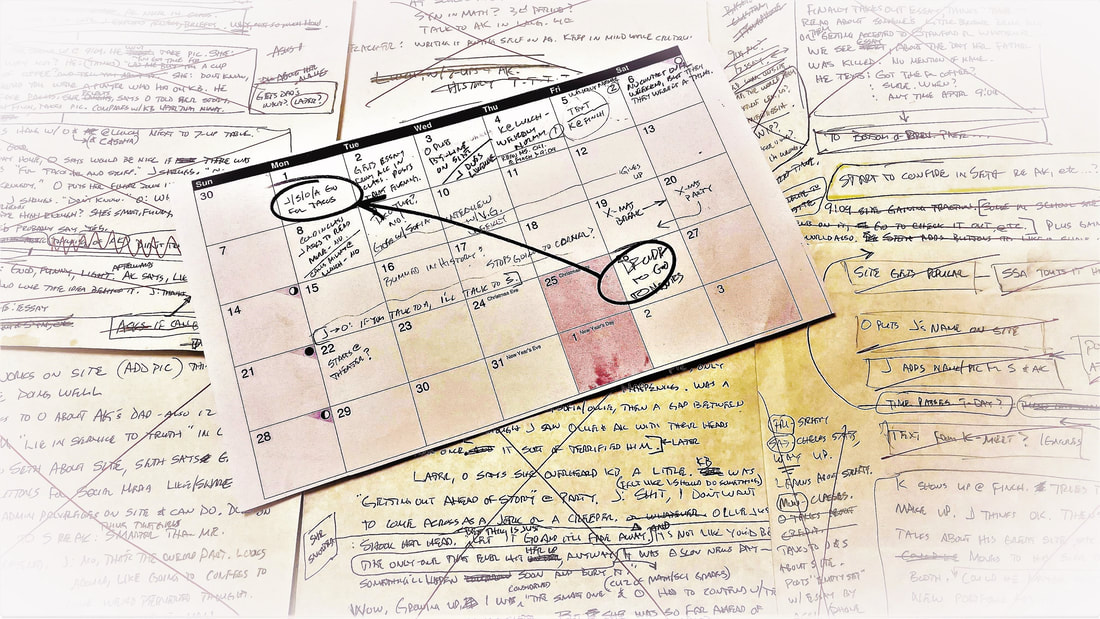

The entire query should be the equivalent of a one-page business letter. (Shoot for under 400 words, shorter being better. If you can cut something and it doesn’t detract from the desired outcome then by all means trim it!) About that desired outcome, always keep in mind the singular objective of your query letter: It leads to the agent/editor reading your sample pages. That’s all. But assuming you’ve done your job with crafting your story, that’s enough. No matter how great your query is or how much time you spent poring over it, if they turn to your pages and they don’t fall in love with (a) the voice, and (b) the actual writing itself, it’s almost certainly going to be a pass. But a straight-forward query (as long as it tells them enough to get them to read your pages) can absolutely lead to what you’re looking for. As I’ve mentioned before, the query is the taxi or rideshare that took you to an important job interview. Yes, it’s important to get to the interview on time and in one piece, but once you’re in the room with the panel, the vehicle that got you there is immaterial. So by all means, have a good query that places you and your work in the best light. But don’t spend an inordinate amount of time and anxiety trying to concoct the perfect query. There is no such thing. Put most of your efforts into what really matters, the thing they will ultimately say yes or no to… the pages. Which we will discuss next time. Happy querying! …so let’s not make it worse. Let's talk process. Emerging writers are stressing out in record numbers, often needlessly. We’ve talked before about the whole “ Theory vs. Practice ” dichotomy, and how there can be a difference between how the conventional wisdom assumes things are and how they really are. In my observation this gap is getting wider almost daily, largely due to social media. If one were to get their writing/publishing info from places emerging writers hangout online (I’m looking at you, Writer Twitter) then they’d likely have a warped view of how all this works. (There’s a similar disconnect between what the online CW would have us believe the query process is and what it really is. But that’s a post for next time…) The reason I mention all this is I’m assuming you’re a writer who loves the craft, who writes from your core, who pours your soul into your work, and who wants to find a process (both for writing and for publishing) that gets you where you want to go… ideally without a lot of dead ends and wasted time. One irony is that the ideas you see being promoted online almost universally promise to save you time… when in fact the majority of people I know—or know of—who try to use these methods seem to take longer to actually arrive at a submission-worthy manuscript, let alone have their work published. And the sad part—when you look at the gap between what people think authors do and what most working authors actually do—is that the methodologies that many authors use are generally much simpler and have fewer variables than the so-called ‘online conventional wisdom.’ So let’s compare and contrast. (Keeping in mind that there is no ‘one true way,’ and I’m not saying that these ‘real world’ methods represent every working writer. Just that many authors I know use something analogous to them. IRL this stuff is on a continuum, of course.) Starting with the writing itself… Social media would have you believe that before you begin writing you need to have a formula or system or structure, containing all the required story beats. (These are available as books, or on websites, or in seminars, or in video form. Lots of this is scattered about the interwebs, but there are plenty of people who will be happy to take your money in exchange for compiling the information for you.) Then you construct an outline, making sure you have all the approved beats in all the approved locations. And you build this whole thing using writing-specific software that will help you ‘structure your story’ and let you move big chunks of story around in wholesale fashion until you finally arrive at an order of events that theoretically has all the right stuff in all the right places. Then you take your “draft zero” and dig into it, turning your roughly-filled-in outline into readable prose after you’ve done a major structural overhaul (using the story-centric software, which you may have studied via an online workshop since the learning curve is pretty steep). Then you track and save all the various revs you end up with as you make revisions, each stored as a separate doc. Because you never know when you might want to go back to a previous version and cut/paste a specific chunk into your current rev. And of course each chapter is a separate document, and you also keep a file on each chapter (also a separate doc) delineating what happens therein, as well as what each character either did or learned in order to further the plot. All of these are numbered in a coherent fashion (i.e. Ch.7.rev.3.2.notes) so that you can access any of them at any time, should it be necessary. Then when you finally feel like you might have all the scenes in your story arranged in the correct order, you compile all the separate chapter docs into one uber-document and export it to a Word doc so you can have it available for beta readers or to send out to an agent if/when you get the much-sought-after, vague-tweet-worthy event: the legendary full request. (Although if your betas have structural suggestions you may find yourself ungrouping the manuscript back into its original components and re-juggling things all over again, then re-compiling it into another full manuscript for Round 2, etc.) On the other hand… For the most part, many working authors I know or know of basically do something resembling this: They get (and develop in their minds) an idea they find really compelling. They make some notes. Or not. They open a word-processing document. They write the book, referring to the ideas in their head and/or the notes they created before starting… or they might write the first few chapters and then pause/plan/plot/ponder and make a few notes about the next phase of the story once they know their character and setting and setup a little better. As they write, they typically have one primary doc containing the manuscript in progress. When they reach the end of a chapter they insert a page break, hit return half-a-dozen times, enter “Chapter 14” or whatever then drop down a couple of lines and keep writing. All one doc. (In TNR 12pt. double-spaced with 1” margins, because duh.) Maybe with a second doc containing notes, although I know a couple of writers who just put their “aha!” ideas at the end of the primary doc and keep pushing them along as they write and either use them or delete them by the end of the book. If at any point during the initial drafting they happen to go back and re-read some previous pages or chapters and they find something clunky, they often just make a quick edit on the spot without saving the earlier version as a separate rev or anything. (The first time I mentioned that I did this—while I was presenting to a writer’s group—I remember a woman up front literally putting her hands to her face in the ‘home alone!’ gesture. In my defense, the saying is “Kill your darlings,” not “Have a giant memorial service for each one,” right?) The same applies during revisions. Unless it’s a major structural rewrite, many working authors doing line-level revisions will revise directly in the original doc, not worrying about saving each earlier version. I think a side benefit of doing this—beyond avoiding strangling yourself with multiple saved revisions—is that it teaches you that none of your text is so precious that it can’t be improved. It also teaches you to have confidence in your authorial vision… if there’s clearly a way to rephrase something that’s better/tighter/more compelling, trust your judgement, make the change, and move on. Then, after multiple rounds of revise/edit/polish—when they feel it’s as good as they can make it on their own—they’ll send it to their agent or editor… with the full knowledge that their agent or editor will have ideas of their own on how to make it even better. Which is all to the good, as I’ve never seen a work that couldn’t be improved via thoughtful feedback followed by further revision. TL;DR: Many working authors follow something roughly analogous to the following… *Get idea, develop it. *Make notes (or not). *Open a doc. *Write the book. *Revise/edit/polish. *Repeat until happy. *Submit. 90% of getting published depends on having a really strong manuscript, so put your time there… into (1) developing your craft, then (2) executing it on the page, and then (3) revising until it’s absolutely as good as you can make it. Stories that will move a reader (including an agent or editor) aren’t ‘assembled,’ like some sort of paint-by-numbers thing. They’re written in such a way that they make an emotional connection with the reader. And almost all of that comes from inside your head, not some formulaic external process. So I would suggest not overthinking it, and not making it any harder than it needs to be. Writing is hard enough without feeling you have to attach a bunch of additional process-related stuff to it. (Unless you want to, of course. You do you.) Happy writing! One of the many things copyeditors do is check the grammar and usage of your character’s dialog, making sure everything is consistent and correct. And when they make a correction to something (specifically, something said by a character or something in interior monologue—which in a 1st person novel is virtually the whole manuscript) and the correction doesn’t reflect what I want the voice to say, I write “Stet, for voice*” in the comments, and they get it. [*Stet is a common CE comment—it’s Latin for ‘Let it stand.’ And ‘for voice’ means we’re leaving this as-is because it represents a character’s authentic voice.] Same with the ubiquitous “friend w/English degree” or your MFA neighbor or whoever you have read your manuscript to make sure everything is “correct”… whatever that means. Except there’s a chance (a good chance, in my experience) they may not fully get the ‘stet, for voice’ concept, and in the desire to make sure everything’s “legal” the aspiring author may likely go along with the ad-hoc recommendations. Which can be dangerous… because correct is not always best. Especially in fiction. Strunk & White-style grammar may not be the same as the way your specific character—with their background, age, and education—might really talk. And having your character speak with perfect, college-professor-level diction is probably going to grab the reader’s attention… in the worst way. Because it doesn’t ring true in most cases. And ‘ringing true’ is a necessity when you want readers to relate to your character as though he/she were a real person. (And you definitely want this, if you want your book to resonate with readers.) Dialog can be tricky. You generally don’t want to exactly replicate real verbal exchanges—with all the ums and uhs and ahhs and you-knows and incomplete and/or incorrectly structured sentences and run-on verbiage, etc. BUT… you also don’t want your characters to speak perfectly, as though they’d written out everything they were going to say and then did a deep edit on every sentence, making it “perfect” before saying it in what is supposedly realistic, unrehearsed, actual, you know, conversation. (Let alone having your characters pass on information to the reader disguised as dialog which the other character likely already knows. This type of “As you know, Bob” exchange is clunky in the extreme and there are so many better ways to convey the information, including just having a snippet of dialog and then having the character tell us via internal monologue some of the non-stated information. Or suppress the need to explain everything and let the reader figure it out via context down the road.) There’s a balance. We want our dialog to feel like real off-the-cuff human speech while not totally replicating the overly-padded content of actual dialog… and we want the dialog to convey something important to the story and help it move forward, whether that’s information or character development (or, ideally, both). But what it very likely won’t be is grammatically perfect. (Keeping in mind the great Elmore Leonard’s dictum: “Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly,” lest we error on the side of clunky, corny, or outright stereotyping.) And while the concept of “Stet, for voice” obviously applies to dialog in the micro, it also—in the macro—applies to your writing in general. We’ve discussed the concept of “voice” before (here) but it’s important to understand that the book’s voice—whether the character’s or the narrator’s, if applicable—might be the single quality that most affects the reader’s pleasure (or lack thereof) on a page-by-page basis. Yes, the plot takes shape as we move through the book, but the voice is right there in every paragraph, every sentence, every word we read. And if the voice doesn’t ring true, if it doesn’t compel us to read on, if it doesn’t make us connect with the character on an emotional level, then the plot probably won’t matter… simply because the reader may not make it to the end. But if the voice grabs us and pulls us into the story and makes us care about the character and what happens to them, we’ll probably follow it no matter what. SO… don’t give up what makes your book unique (your character with their own specific voice) simply because they don’t always utter the King’s English. This doesn’t mean anything goes… that you can have your character speak in a wildly inconsistent manner, that the character’s voice can be a total mismatch for their personality, that you can sling slang all over the page and not have it throw readers out of the story. You still need to be in charge of the character’s voice, and the decisions you make regarding it need to be made with an eye toward the overall effect on the reader. (Developing this sensibility to where you apply it almost unconsciously is a perfect example of the level of craft that comes from practice, and knowing when you’ve overdone it—and are willing to revise it back toward the norm—is yet another level of experiential aptitude. As is a willingness to listen to cognizant feedback about these things… from your editor or elsewhere.) Ideally, your character’s voice—and how you choose to portray it—is another tool for your creativity to express itself when it comes to crafting something that’ll have a compelling emotional impact on the reader. A powerful tool. Don’t give up this power in the name of perfection.

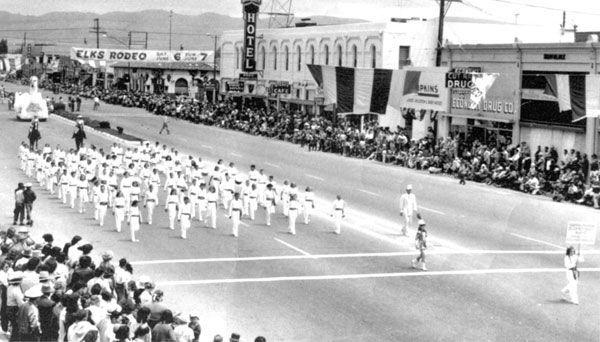

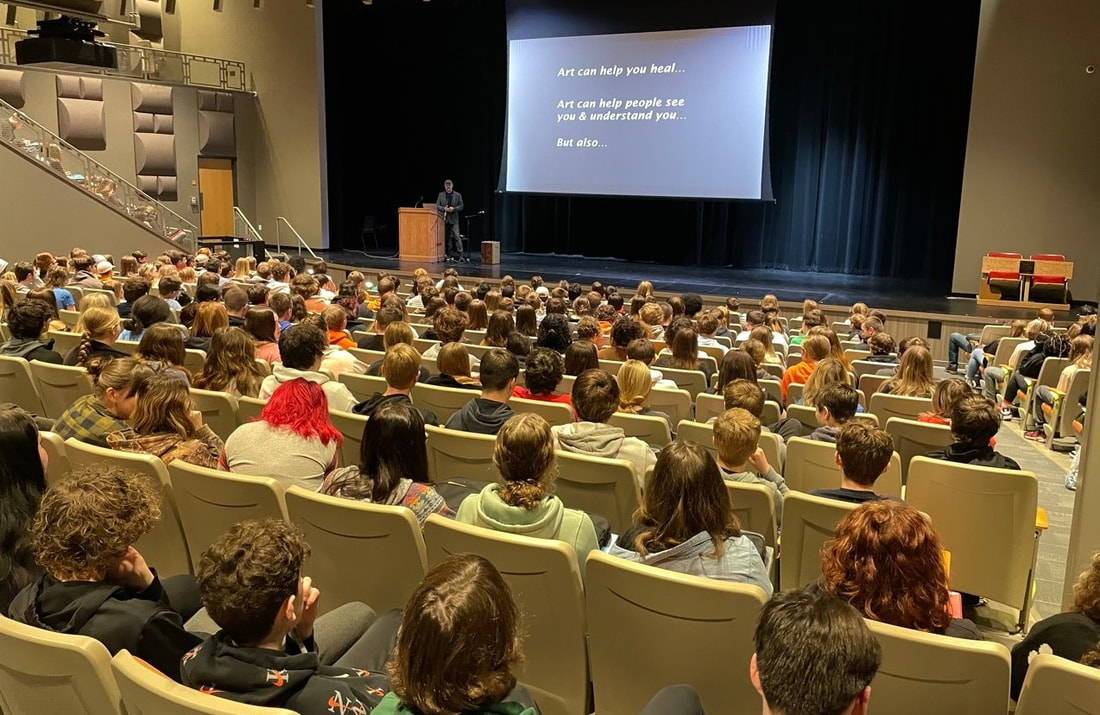

These things seem to come in waves. I did a little tour last fall (for 9:09 – maybe three weeks) which—along with a number of in-store signings—included half a dozen school and library type events, so I developed a basic presentation that would work for most of them with a few tweaks. But then we went out on a larger/longer tour this spring which—as anchor points between in-store events—included things like doing the opening keynote at the awesome Colorado Teen Lit Con, along with some larger school events and a few writing classes, etc. And a couple of months before we left, I looked at the itinerary, gulped, and said to myself, Holy crap, you’re gonna need some all-new programs… maybe several of them! This can feel daunting as your brain spins around the questions of: Where do I start, what do I do, and how do I do it…??? However, as with drafting almost any how-to nonfiction piece, it can help to begin with a structure. And not to get all instructor-geeky on you, but one of the best ways to develop a new program is to use the tools of the Standardized Approach to Training: A.D.D.I.E. (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation.) Don’t shudder and run away. Those are just fancy words describing a common-sense way to decide what to do, how to do it, and how to determine if it’s working. As follows… Analysis: This initial step is where you determine what sort of presentation you’re going to build and give, based on the needs of your attendees. (Which could be school students, bookstore customers, conference attendees, workshop clients, etc.) These each have different needs. School presentations should be educational and entertaining. Bookstores have a fairly general audience with an obvious bias toward reading. People attending workshops are writing-centered and typically place a higher focus on actionable information and advice than entertainment. (Not that it needs to be bone dry… humor is almost always welcome at the right times.) Design: Decide on an overall structure and make an outline for your presentation. (Examples: maybe a PowerPoint with lecture for conferences; “Draw and talk” for those of you who both illustrate and write; Storytelling with props for story time type events; a specific how-to lesson with guided exercises for workshops; etc.) Development: Take your outline and fill in all the details. In other words, add meat to the skeleton by actually building the presentation you outlined above. Just like writing a story, don’t expect to get it perfect the first time. It’s an iterative process… write/revise/write/revise until it feels smooth and tight. (Leaving some room for on-the-fly improvisation, if that’s your vibe.) Implementation: This is (theoretically) simple: you give the presentation you designed and built. But for many this is the hardest part—getting up in front of a live audience and presenting your material in a way that comes off as smooth and professional, yet personable and entertaining. Everyone is different and there are whole books on dealing with public speaking so we’re not doing a deep dive here, but there is one tactic that seems universally helpful: practice. I’m fine speaking to customers in a bookstore or presenting to kids, but frankly, doing a more formal presentation to a room full of writers or educators can make me a little nervous. What helps me is going somewhere quiet and giving the presentation—aloud—multiple times, well in advance of the event. Evaluation: How did it go? Any slow spots where the audience seemed bored or antsy? Did the presentation run long… or did you run out of material halfway through? Any pertinent points you failed to make? This is where we close the loop back to ‘Analysis’ and make any possible improvements after the fact. Use your own assessment, but also touch base with a friend or acquaintance who attended, if possible. Sometimes presenters have a form for receiving feedback from attendees, depending on the nature of the event. Whatever the feedback, roll the actionable parts of it back into the ADDIE loop and make the next version even stronger. (But don’t over-think this. Give a few presentations and you’ll start organically making changes/improvements to the material without even thinking about it.) Some tips from the trenches: Pay attention to overall time during the dry runs. If you have 60 minutes to present, don’t have a presentation that takes you 60 minutes to get through. You’ll almost certainly lose a few minutes to admin stuff and introductions at the start and other things will crop up, and you’ll either end up rushing to finish it or you’ll have to end in the middle of a section—both less-than-optimum. Instead, plan accordingly and make adjustments as you get close so you end on time. (Sort of like a “two-minute drill,” if your closing segment takes five minutes, segue into it six or seven minutes before the end time so you can stick the landing without zipping through the most important parts.) If you’re planning on a Q&A section, budget adequate space for it. ‘Adult Education’ is primarily about giving your attendees actionable information (i.e. stuff they can use) as opposed to entertainment or broadly educational content. In longer workshops I’ll often build-in a Q&A break after each section, and sometimes almost half of the overall class can be Q&A. Get to know your specific audience. I’ll usually do a quick show-of-hands assessment to find out who’s there, their experience level, and what they really want to know. Then you can adjust your presentation accordingly and put a little more focus on their specific needs. Remember why you’re there. You’re there to give your audience something of value, whether that’s motivating kiddos to read, aiding emerging writers in navigating the publishing industry, or helping workshop clients construct tight dialog. It’s about them, not you. To that end… Skip the long self-intro. They probably know who you are and why you’re there—no need for the whole ego-boosting CV. A quick “My name is X and I’ve done Y” should suffice. (Or better yet, just jump right in with some interesting/useful information and hook them from the word “go”.) Try to take video (or at least an audio recording on your phone) of your early presentations or classes and review them with a critical eye. I did, and learned that once I’m wound up and going, I can start talking too fast if I’m not careful. It’s amazing what we can learn by listening after the fact when we’re not caught up in the moment. Have a “contact” page onscreen at the end of your presentation where appropriate, for any follow-up and/or feedback. Always thank your host (festival or bookstore or school or conference or library, etc.). It’s a lot of work to put on whatever event you were part of, and people appreciate being appreciated. Plus, one of the best ways to get further offers to present is positive word-of-mouth from previous hosts. Happy presenting! You’ll often see two conflicting pieces of writing advice: (1) Don’t have an unlikeable main character. (2) You don’t have to have a likeable main character. The first is one of those ‘conventional writing wisdom’ things, right up there with “Show, don’t tell” and “Write what you know.” And I think it’s about as misunderstood as those old sayings. The second is newer (relatively speaking) and often bolstered with references to unlikeable characters in TV and film properties. (House of Cards, anyone?) So, which is it? First of all, there are no rules to writing fiction, right? So do whatever works for you and your readers. And what works for most readers? Having a compelling character. Which isn’t the same as a likeable character, but in the Venn diagram of writing there’s a lot of overlap between them. There’s also some overlap between a compelling character and a “Can’t take your eyes off her” diabolical villain. Either can work as long as you keep in mind that readers have a few different ways of finding their way into a story. Many readers like to identify with the main character. In a well-written 1st person POV novel (or very close 3rd), this character-identification can almost feel to the reader like they are the main character, either going through the story right there with them, or actually as them, depending. Either way, the protagonist has been crafted such that the reader really cares about them and what happens to them, on an emotional level. This type of connection is the sort of thing that can lead to certain stories attaining the status of “beloved.” There are also many readers who are entertained by interesting villains. But most of us (thankfully) don’t closely identify with evil people, so the deep emotional connection described above may be lacking. Ex: Harry Potter is a beloved story, in part because people tend to identify with (and have sympathy for) an underdog character who’s good at heart. Voldemort is a strong villain, but while HP without Harry and Co. might be a fascinating study of evil, it wouldn’t have nearly the “empathy” factor of the same story with Harry and Hermione and Ron, etc. So the question becomes: Do I want people to be able to identify—on some level—with my main character? If yes, then your character should of course have imperfections and moral complexities (nothing is more boring than perfection), but still come off to some extent as sympathetic and having those human traits which most of us admire and may want to identify with. And if no, then make your unlikeable character as interesting and compelling in their evilness as possible, in hopes of capturing those readers who don’t need to empathize with a protagonist. (Or try doing both, via the use of the anti-hero. It’s quite a balancing act, but the morally grey character can be quite compelling while still engendering sympathy if done well.) All the above is a discussion of the value of purposely unlikeable protagonists. But in reality, many complaints about ‘an unlikeable main character’ are actually aimed at unintentionally unlikeable characters. We’ve all read books where the protagonists weren’t cruel or evil… but weren’t necessarily people we cheered for either. This can be caused by them coming off as annoying or spoiled or self-centered or thoughtless or any number of similar attributes. Not that characters (and real people) can’t be these things at times, but if they primarily come off as annoying, you’re going to have a hard time getting the reader to even like them, let alone empathize and/or identify with them. One way to avoid this is the use of a few trusted betas who will be honest enough to tell you, “The story was well written, but I didn’t really love the main character and I didn’t really care what happened to her.” This sort of feedback can be gold to you, because if your readers can’t bond with your main character, they very likely won’t bond with your book. (The external viewpoint is invaluable here because we usually love our protagonists—after all, they came from us—so we may not immediately grasp that they may not be as appealing to other people.) So, to re-write the above axioms: (1) No matter what, you want a compelling main character. (2) And if they’re someone with whom you wish the reader to identify, try to craft them in a way that doesn’t preclude this. Because some level of emotional connection between your work and your reader is vital if you want the work to resonate long after they turn the last page. Happy crafting!

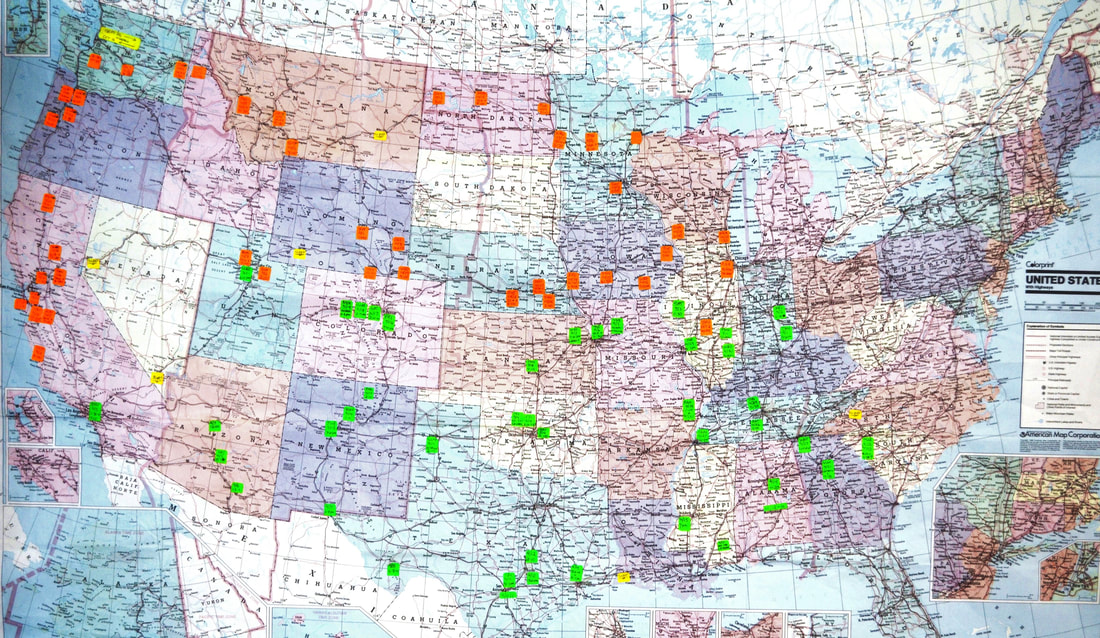

I may be shoveling sand against the tide here but there’s a pervasive paradigm within the writing-centric social media community that does a pretty serious disservice to aspiring writers. In short, there’s a lot of stress, importance, energy, time, and focus being put on things that aren’t primarily writing. When in reality… The way you get better at writing is by… writing. The way you create a strong manuscript is via writing. The way you acquire representation is through your writing. The way you get acquired and published is through your writing. What makes readers want to buy and read your work is… the writing. Man, it’s all about the writing. All those other things only come from the writing. That’s the place to put your focus… if you actually want to be a writer. (I qualified that statement because there’s a subset of people who want to ‘have written,’ and/or want to ‘have had a book published,’ for some imagined perks that have nothing to do with actually loving—and improving at—the craft of writing.) In this sort of environment, is it any wonder it’s easy for emerging writers to get distracted by all the non-writing aspects of the whole ‘being a writer’ thing? Your attention—your focus—is like the money in your wallet… you only have so much of it, and if you want to make it to the next payday you need to think carefully about where you spend it. I see people spending lots of time/energy/focus (and angst) on non-writing things like… Becoming ‘agented’… (Pretty sad it’s an adjective these days.) Being published… Doing book signings… Doing school presentations… Speaking at conferences… Winning awards… Making ‘Best of’ lists… Hitting certain sales numbers… These are all things a writer might do—on the periphery—but these things aren’t writing, and focusing on them won’t make you a writer. Only writing will do that. And—not coincidentally—the people who actually do the above things seem to be people who put the craft of writing above any sort of ego boost they might get from accomplishing those peripheral things. And, as nice as they are, those things aren’t even close to being the best part of being a writer. Writing is the best part. By far. If you don’t love the craft of writing—without any of the supposed perks—you’re likely to be sorely disappointed if you’re trying to acquire the “writer’s lifestyle.” So to those distracted/disappointed/depressed by all the current negativity on social around the whole subject of ‘being a writer,’ my best advice is to not waste any energy worrying about that crap and put your laser-sharp focus (and your time and your effort and your love) where it actually matters… on the craft of writing. The goal over which you have total control (and—in an interesting karmic twist—the one most likely to get you all those peripheral things) is simply to become the best writer you can, and to write the best book you can. Focus. Something worth keeping in mind with any creative endeavor: The thing that represents the work is NOT the work itself. No one confuses notes on a staff with actual music or thinks that a set of house plans is in fact a building… yet with writing it can be all too easy to conflate the representation* with the actual thing. [*Have you noticed that most AI-generated stories read like a plot synopsis? A really shitty plot synopsis? Because for the most part, that’s what they are. Reading them, we’re rarely – if ever – actually ‘in scene,’ and virtually never to the point of immersion where we forget we’re reading something and are lost in the story. That’s because they’re basically just a structure… a composite based on an amalgamation of several other story structures, assembled into a single construct by a high-powered algorithm. And of course, most “write your novel now!” sites are all about following this same path. As discussed here. Often with similar results.] I think part of this comes from us thinking of the story structure (the plot) as the story itself, when the plot is just the framework on which we build the actual story. Imagine someone wanted to create a wonderful dress. Something unique and beautiful and amazing, which—hopefully—others might love as well. But instead of thinking about a one-of-a-kind design, using flowing fabrics with interesting colors and textures and shapes, they spent their time worrying about getting the perfect mannequin. Maybe one that represented the largest cross-section of people—or maybe one considered the ‘ideal’ size—so that their work might appeal to the largest number of people. All with little thought to the dress itself. That sounds goofy, yet it’s analogous to what we often see… fealty to the minor god of “subject matter*” over other considerations… like story and character and emotional connection… and the actual craft of the writing itself. [*You will often see on social media an aspiring writer bemoaning the fact that an agent or editor called out something specific in their #MSWL—for example, “Love to see an MG about a mystery set at summer camp!”—and the writer turned in something they thought fit the bill… and it was summarily rejected. And they don’t get it, because they sent the agent “exactly what she asked for.” I understand the frustration - as far as it goes - but it’s important to understand when an agent or editor mentions something like the above in their wish list, what they’re actually saying is, “I’d like to see a really well-written, emotionally compelling middle grade novel about a group of kids—sort of on their own, away from home—solving a problem together.” With the unstated ‘well-written, compelling’ part the most important criteria, by far. Again, it’s really about the dress itself more than the specifics of the mannequin, right?] If you gave the same basic plot to a bunch of different writers, you’d get a bunch of very diverse books. Because each writer is unique, with a different voice and life experience and perspective on the world. Thinking it could be otherwise would be like thinking if you took a dozen different dress designers and gave them all the same mannequin to build a dress upon, you’d get twelve identical dresses. I’m not saying a mannequin isn’t an important tool to a dress designer. Of course you want a shape to build the dress upon. But the mannequin is in no way the dress itself. The story--your story—is the singular thing you have. Your voice, your vibe, your viewpoint… your weird take on life that makes your stuff interesting and unique and oddly compelling. That’s what you have. And the journey your character goes through as they transit the events in the story is the thing that shines a light on what makes you and your viewpoint worth reading… not the scaffolding. Happy dressmaking! Seems like we all get told the same platitudes regarding writing, like “Writing is rewriting,” “Show, don’t tell,” and of course, “Write what you know.” It’s that last one I was to explore for a minute. I think it’s valid, but maybe not in the reductive way some people mean it. I was doing a discussion/Q&A with a group of writing students a couple of months ago, and I got a new question. Instead of “Where do you get your ideas?” (discussed here) or “How do you deal with writer’s block?” (discussed here), someone asked, “When did you first know you wanted to be a musician?” Wow. The last-second switch from the expected “writer” to “musician” sort of threw me. I mentally reviewed my options: I joined my first band around twelve. But I got my first drum set around eleven. But I had a brief fling with electric guitar at ten. But I saw my first band around eight or nine. All of those mattered, but the actual event that started everything—maybe even me becoming a writer—happened even earlier. When I was a little kid of maybe four, I was with my family at a parade in our hometown… just your basic small-town summer parade. Somewhere amidst the baton twirlers and horseback teams and dignitaries in convertibles there was a marching drum corps. My dad had hoisted me onto his shoulders for a better look, and when they got near us those drummers started playing. Suddenly… all of them at once… at a very high volume. My God, I’d never felt anything like it! The thundering of those drums shook my chest (and in my mind’s eye, blew back my hair), but it also did something to me on the inside. Permanently. The raw power was so attractive… I immediately had the feeling of, Whatever that is… I want it! And that was that. After I’d explained this ‘big bang’ inciting incident I realized it was a teachable moment, for both me and the students. I said that yeah, following the adage of “write what you know,” in theory I should write a novel about a kid at a parade who becomes a drummer, blah blah blah… But I’d already written a book about a young drummer and I didn’t want to re-tread similar territory. But… what if I wanted to write a story about a young race driver? Maybe he started with go-karts and moved up to destruction derbies and stock cars, eventually becoming a pro NASCAR driver. I’m not an expert on motor racing, but what if I took the experience of me at the parade and authentically recast it… maybe the boy was four or five and he was with his dad at the track for the first time… maybe standing next to the outside rail… maybe his dad hoisted him for a better view… maybe when the cars roared around the first corner toward them, the raw power and the deafening noise—and the smell of gas and oil and burning tires—imprinted on the boy, and he knew that whatever the heck that was… he wanted it! And from then on, his heart was permanently betrothed to gasoline alley. I haven’t been there. But man, I’ve been there! I don’t need to know the technical specifics to get in touch with the emotions that come with those early peak experiences. And neither do you. We just have to mine those experiences, remember how they felt—viscerally, not intellectually—and do our best to forget the limiting specifics and transfer that authentic emotion to our character. We’ve all experienced moments of heightened emotion. Ecstatic, terrifying, validating, heart-rending, uplifting, soaring… We can use these… not by putting our character in the exact same situation we’ve been in, but by putting our character in a new situation while allowing him/her to experience the full emotional rollercoaster that comes with those watershed moments. Because, even if you don’t know, first-hand, all of the specifics of your character’s situation, you absolutely know how it feels to be in those moments when everything seems more. Even if you haven’t been there, you’ve been there. And you know. So… write what you know. There is “the theory of” and “the planning of,” but sooner or later you’re faced with “the doing of…” A typical day on book tour might start with packing up* and checking out of the hotel, then traveling to the next stop where (assuming you’re a PB/MG/YA author) you may have a mid-day school visit. [*We learned early on not to unpack and put clothes in the dressers or closets. Suitcases on suitcase stands are way more efficient and you won’t leave things behind. We prided ourselves on how quickly we could move in or out, humming the “Mission Impossible” theme while doing it.] These days you should add an extra fifteen minutes when presenting at a school, because you’re almost certainly going to have to visit the admin office first (at many schools, there is no other way to physically access the campus) and sign in, receiving a visitor’s badge. Then they’ll get the librarian or teacher who coordinated your visit to escort you to the auditorium/cafeteria/gym/MPR for your presentation. Go to the venue and prioritize getting the tech up and running before doing too much meet-and-greet. Almost all schools will have someone to help with this, and they range from total tech wizards to flustered/overworked teachers who aren’t familiar with the equipment. Pro tip: have your presentation available on a thumb drive for use and backed up on your computer as well as in one other location, preferably online. (Or vice versa. We try to use their equipment and present off our thumb drives when possible, but more than once the day was saved because we had our computers with us. Multiple cables & adaptors to interface between your computer and their projector/system are worth their weight in gold. I also bring a small USB “pointer/clicker,” because there’s nothing that kills the flow of a presentation more than having to run back to the computer to advance each slide or waving at someone to change slides for you. And finally, be able to give some semblance of your presentation without any technology at all, because sooner or later you’ll have to. Trust me on this…) You’ll want to have an educational component in your presentation (teachers, librarians, and principals will appreciate this—you’re at a school, after all) but also something entertaining for the kiddos. And while you definitely want to talk about your work at some point, what you don’t want to do is simply show all of your books and give a sales pitch for each. (No one will like this approach, adult or student.) Don’t forget to give credit to the store that selected the school. (My brilliant wife makes a slide for the top of each show that basically says, “Sponsored by XYZ Bookstore” with the store’s logo, and this is up when the students are filing in. Often the store will have a rep at the school, either to watch or to hold a sale afterward. They always appreciate the shoutout.) At the end, also mention you’ll be at the sponsoring store that evening to take questions and sign books. After the school presentation—and some version of checking in/unpacking/eating—you get to the bookstore. As with a school, it pays to arrive a little early. Greet the owner/coordinator, get the lay of the land, browse the shelves if there’s time, meet some customers if there’s time, grab a coffee if available, and get ready for your presentation… As mentioned previously, there are a few different types of signings. Your mileage may vary, of course, but here’s how I broadly categorize them… “Sit & Sign.” This is where the store parks you somewhere (typically near the entrance, or maybe in your genre’s section if it’s a big store) at a table with a stack of your books, and you’re left to try and engage customers as they walk by, hopefully leading to a discussion and maybe even a sale. These are usually not the best experience, and we try to avoid them if there’s another option. You’re engaging with people who aren’t there to see you and likely aren’t even interested in the type of book you’re presenting. There’s no real draw to this sort of signing (unless you have fans/friends/readers in the area who will make the trip to see you) other than the fact that it can lead to signing a fair amount of stock. (Seems like the larger chain stores tend to go for this, so sometimes the stock signing can be significant. When we sign stock we always volunteer to put “signed by author” stickers on the books, because it increases the likelihood that book will sell down the road. Chain stores will have a big roll of these, or you can bring your own to smaller stores.) Also, as there is no actual presentation, it’s harder to give the customers much of value during a sit and sign other than occasionally taking questions one-on-one. “Read & Sign.” This at least offers customers the ‘value’ of hearing you read from your work. (Usually your latest, which they likely haven’t read yet… like a trailer or teaser for your new book.) I put value in quotes because you’re giving them something they can get simply by picking up the book and perusing a chapter. I’m not a huge fan of readings—either as attendee or presenter—but if the audience consists primarily of fan-ish readers (which it usually doesn’t—see below) then this might work well for you and your attendees. At least you typically have the trappings of a presentation—chairs for them and a place in front for you—and there is some interaction between reader and author. And of course you can do a Q&A afterward, which is even more interactive. “Presentation w/Q&A.” This is our favorite, because it has something for everyone. As mentioned, a high percentage of people want to write a book. (And of course, some of them are actually writers, actively writing and/or trying to publish. These people are even more interested in speaking with you.) The details regarding how to decide on the specifics of an author presentation might make a good post unto itself, but a few popular topics include “where writers get ideas,” “the journey to publication,” “making the creative life work,” “the writing process,” and “a peek behind the publishing curtain.” A variation of this is the “In conversation with…” presentation, where someone (often another writer, or perhaps one of the store’s staff) will interview you. Either way, a conversation is almost always better than a one-way delivery. A big key to reaching the audience is knowing who you’re addressing. We sometimes do a quick assessment first (via a show of hands) regarding how many have an interest in writing someday, how many are actively writing, how many have a draft they’re in the process of shopping, how many have no interest in writing but are avid readers, etc. Then we tailor the presentation to them. Another key factor is not making the presentation about you. Ideally, it should focus on them, and give them something that can help them get where they want to go. (There’s nothing more boring than some dude droning on and on about himself and his books, his story, his process, his life, etc.) And of course, the way to make sure you’re giving the attendees what they want is to be as interactive as possible. Sometimes the bulk of the presentation ends up being a lively hour-long Q&A session. (Again, a bunch of concise answers will usually be better than a few long dissertations here. Regardless, we always try to do a “lightning round” near the end where we answer a bunch of questions quickly, because there’s nothing worse than someone sitting through a presentation and not getting a chance to ask their question.) After you’re done you sign books for the attendees, of course, and always be sure to ask the store if they’d like you to sign stock. And… always thank the staff profusely for hosting your visit. This is a mutual-aid thing. Yes, you’re taking the time to present, hopefully bringing people into their store, maybe even new customers. But they’re allowing you to present your work in their establishment, which costs them in terms of time/work/money. You want to leave them feeling good about you and your books, and they want you feeling good about their store. Win-win, right? I can honestly say we’ve met booksellers and school librarians who’ve become lifelong friends through doing events with them. Which shouldn’t be too surprising. After all, we have a shared love of books. Happy touring! “If you build it, they will come” doesn’t necessarily apply to book events. It’s more like “If you build it--and tell them all about it--some of them might come.” Yes, there is the rare store that has such a strong, loyal customer base that you can just show up and there’ll either be a decent sized crowd waiting or they’ll flock to you from around the store once they see an author presenting, but depending on either of those is a very bad bet. And unless you’re hovering near the very tippy-top of the NYT bestseller list, it’s also a mistake to think that your name alone will bring in a crowd. One obvious challenge with a book tour is that you’re not in your hometown. When you do a local book event—assuming you have a new book out and you haven’t done anything local in a while—you can tell all your friends and family and co-workers about it, and get a pretty good turnout from just that. But that doesn’t apply when you’re hundreds or thousands of miles away, in a different state, where you know virtually no one… and very few of them know of you. So, you have to ask (and answer) the question: Why would someone come and see you if they didn’t know you, and/or didn’t know your books? The answer is two-fold: They have to know about the event, and they have to be interested in the event once they learn about it. Let’s take the second part first. People are generally interested in information that can benefit them. I mentioned this last time, but multiple surveys have shown that something like 85% of all adults want to write a book, typically a novel or perhaps a memoir. (And a smaller but still significant number have started writing.) We can provide value to them (beyond talking about our latest book) by stepping outside our specific genre and addressing this broad area of interest directly, as follows… When we were calling stores and the event coordinator/owner/manager would find out we wrote MG & YA, she’d often say “We don’t usually have good luck with kids’ events, and worse with teens.” And we’d say, “We agree completely. We have better luck when we position it as: Two published authors are going to talk about reading and writing and the publishing business.” And we’d promote it that way. And it generally worked. Often we’d have a good turnout with lots of engaged people at the event—asking questions and buying books to get signed—and there wouldn’t be a kid in the room. We’ll talk about presentation specifics more next time, but for now you should come up with a general theme and pitch for your presentation. We call our joint events the “He Said, She Said” presentation and it’s largely based on us riffing back-and-forth on reading, writing, publishing, and living the writing life, and at least half of it is Q&A. (Remember, your goal is to give the attendees something they’ll value, not just find different ways to say “Here’s my book, buy it now!”) And my solo events cover largely the same territory, often focusing on the power of art. Again, with lots of Q&A. So now that you have something that—hopefully—people will be interested in (and that the store’s event coordinator will feel the same about), you want to help get the word out. Sure, you should definitely put your tour schedule all over social media because once in a while someone will show up from seeing that. But really, your strongest move is helping the store let their customers know. Easy things first. Make an electronic poster for each event with all the pertinent date/time/presentation info (as well as graphics of you and your book, of course) and send it to the store. They can print out and place the posters wherever they see fit. Also send them high-res graphics of your book cover & author photo, so they can use them on their website and their social channels and in their email newsletter, etc. When time allows we’ll sometimes send out a turnkey press release—specific to the store, time, and date—for the store to use with their local press outlets and/or social media/newsletter posts. For our big tour we also made a nice overall tour poster which had all the images & info about us and our presentation, with spaces for each store to fill in their specific date and time, then we printed out a hundred of them at 11x17 and sent one to each store on the tour ahead of time. We made a fun (okay, some might say corny) little “tour trailer” video which we sent to all the stores as well as posting on our social accounts. This gives the stores an idea about the vibe of our presentation, and lets them post it on their social accounts to let their customers know a little about the event. Along with this we did a TV interview or two along the route, usually the day of the evening presentation in that market, as well as getting press in some local papers for the same reason. And finally, make sure the store has your book in stock for the event. (Don’t laugh. It seems obvious, but on our very first out-of-state stop on the big tour—in Arizona—the store had my book but not my wife’s, and then in Minnesota the opposite thing happened.) Your publicist can definitely help here, as they’ll get in touch with their sales rep for that region and make sure the store has your books. Another piece of insurance is to contact each store with a quick message a week or so out saying, “We’re on the road headed your way—can’t wait to see you on June seventeenth!” or whatever. (We had one store cancel on us after we’d already started the tour, but luckily we found out ahead of time due to the above and it saved us driving halfway across Mississippi for a non-event.) Okay, the pump has been primed: the store knows, the customers know, and the books are in stock. Next, we’ll wrap up with the day-to-day nuts & bolts of in-store events. Last time we discussed the overall steps in setting up a book tour. Let’s look at some of the important specifics around booking the events as well as scheduling your travel. 1. The Pitch. Believe it or not, not every store you contact will immediately say “Oh my God YES OF COURSE!” when you ask about doing an in-store event. It takes time and effort on the store’s part to put on an event, as well as ordering in your books for it, etc. So the store has to do some quick and dirty ROI calculations to determine if they’re going to have a fighting chance of making a few dollars and/or bringing in some new customers in exchange for their time and effort. All of which boils down to your ability to bring people into the store. Once you let the store know you share the same goals—bringing people into their store—and it sounds like you have a realistic view of how to do that, they’re more likely to want to have you do an event at their store. (More about this in Part III, but a big clue here is that approx. 85% of all adults want to write a book.) 2. Setting the Time and Date. Stores know their local customers and the best times for presentations (and you’ll want to defer to their experience) but much of this is common sense: weekday visits usually happen in the evenings, after dinner but not too late… like 7:00 PM or so. Sometimes I’d be booking a Tuesday in Georgia and the store would say, “We like to do author signings on weekends,” and I’d have to say, “Well, we’re coming through Atlanta on Tuesday… by Saturday we’ll be in St. Louis,” or whatever.* [* But be advised, this is NOT “business hardball.” They’re a bookstore and you’re an author. You both love books, and you’re on the same team. While you certainly don’t want to cool your heels in a hotel room for three or four days waiting for the “perfect presentation slot,” we would occasionally defer for a day under special circumstances. (Ex: Apparently NOTHING happens in Nebraska during a Cornhuskers game, so we had a day off in a hotel in Omaha on a Saturday, which is usually a prime day.) But overall the stores were almost universally accommodating to our schedule… we managed to present six-plus days a week for four months during our biggest tour.] 3. School Visits. As opposed to in-store events (which are free), school presentations typically include an honorarium. (See this post on some issues associated with doing free school visits.) But while we were on book tour, when scheduling allowed we would occasionally tell the store that we’d donate one joint presentation—free—to a local school of their choosing, during the day of the store event. There were several reasons this made sense…

4. Booking Lodging. We booked virtually everything online in advance. At first we booked a few weeks ahead, as we traveled, but after a couple of close calls we started booking further in advance, and by the time we did the second leg of the tour we had everything locked down before we even left the house. Logistics matter here, and you can optimize your hotel time with a few little tips regarding how you juggle your presentations and lodging: We booked in one of three general configurations: the “sign-and-sleep,” the “hit-and-run,” and the “two-fer.” The sign-and-sleep is your basic “Do the evening event, go to your hotel and sleep, then get up and drive to the next stop” routine. And it works fine, especially when you have quite a distance between stops. The downside is you don’t get the best bang for the buck, hotel-wise… you’re either checking in during the afternoon then grabbing dinner and doing the event, or—depending on how far you had to drive—arriving in town then eating, then doing the event, then checking in and hitting the hay before getting up and driving on. If we didn’t have a super long drive to the next stop and/or if the event was reasonably early in the evening, we’d do a hit-and-run, which meant instead of sleeping in the event town we’d do the signing then immediately drive to the next stop and check in… where we’d usually have a two-fer. (Two nights in the same place.) That way we’d wake up and have the whole morning (or day, if no daytime event) to hang out at the hotel, go for a run or swim or sightsee, and get in some serious writing time down in the lobby with coffee and snacks. Then after the evening event we could just go back to the room and hang. You get more “hotel time” for the same outlay, and of course you only have to load-in, unpack, pack up, and load back out once instead of twice. We did this whenever we could, and it always felt like a luxury when we could have a day to hang out or sightsee without having to pack up and drive. (We presented six or seven days a week, so any little break was welcome!) Regarding rooms, our basic priority list when booking was: