|

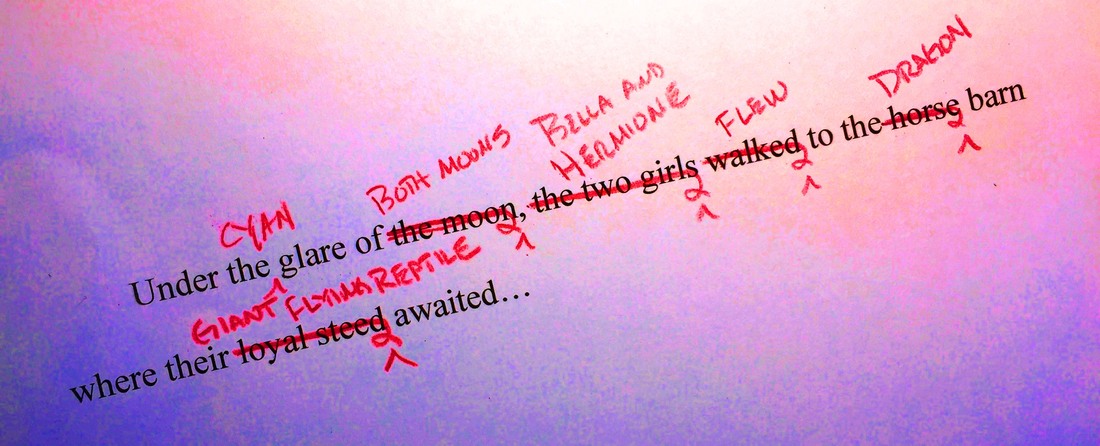

As always, when discussing writing we need to remember that this is an art, not a science. So rule #1 here is: Do what works for you. Period. Which means my thoughts on the matter are exactly that—just my thoughts. Not a prescription for you or anyone else. (IOW, I’m saying “This worked for me and some people I know, it might work for you,” as opposed to “This is the one true way!”) So with that out of the way, the first thing to consider regarding betas (before even selecting them) is: Do I want to use beta readers? If you follow any writing groups on social it seems like using betas is widely considered an automatic must-do, but it's really more of a personal choice than a requirement—I know authors who use them and authors who don't. Which sort of begs the question—what do we expect to get out of a beta reader? Here’s what not to expect: someone who will read the book and tell you how to make the story stronger, better, tighter, more resonant. The person who can do that is a professional editor, and even then, expect to do most of the heavy lifting yourself once they shine a light on some areas where you might improve it. A beta reader is exactly that… someone who can read the manuscript and tell you how they felt about it… as a reader. That’s it. They can tell you where something didn’t work for them. But not how to fix it. (That’s your job.) I’ve heard the different levels of feedback described as symptom/diagnosis/cure. You might mention your symptoms to a non-medical-professional friend, but you probably wouldn’t depend on your friend providing a scientific diagnosis. And you probably wouldn’t take their advice regarding which meds to take w/o consulting a doctor first, either. With a beta, you want them to tell you what didn’t work for them. But if you simply get “I didn’t like it,” that’s not much value unless you can dig a little deeper (without getting into the whole diagnosis/cure aspect). Try not to lead the witness, but attempt to at least get some generalities about why they didn’t like it. (“Too much dialog” is a far cry from “too violent,” right?) And if they can’t tell you in a short declarative sentence what they didn’t like about the scene in question, you need a different beta. (The two most common comments when friends/family read something--“I loved it” or “It wasn’t really my cup of tea”—are equally lacking in constructive value.) So the first realization is: the right beta (for your work) is going to take some work to find. And the second realization: the wrong beta is worse than no beta. Right off the top, they should be very conversant with the genre you’re working in or it’s just general advice with no deep connection to the work at hand. Because what you’re looking for is: a representative member of the likely group of readers for your work… who can also clearly articulate their feelings about the manuscript in question. An SF fan who doesn’t really grok what you’re trying to do is of little value to your emotionally-driven science fiction novel, even though he knows the genre. And a longtime reader who has no experience with young adult literature since “The Outsiders” probably isn’t going to provide actionable feedback on your contemporary YA novel, even though she’s highly literate outside the genre. You need both qualities, although the “able to articulate their feelings about the manuscript” is probably the more important aspect. And finally, they need to understand that a discouraged writer is a bad writer. Which is why you don’t want someone who will tell you ‘the unvarnished truth.’ First, there isn’t much objective truth in art. It’s subjective. It’s emotion. It’s opinion. (If you revise your work in a panic every time someone gives you a differing opinion of it, you’re going to have a hard time maintaining the steady authorial vision required to finish a cohesive work.) Second, you want a little varnish. If your beta can’t find something motivating or validating or inspiring to say about your work, you have to wonder about their mindset, right? I mean, nowhere in the job description of a beta reader does it say: “Find and report every possible flaw you can discover within this piece of writing. Period.” People who look at reading a manuscript as this kind of challenge—and their name is legion—aren’t people you want looking at your early work, believe me. Third, they should already have an affinity for the type of work in question*, or why have them read it? I mean, “a representative member of likely readers” sort of implies they like the genre. If someone says, “I just can’t get behind mysteries,” I might say, “That’s fine—read what you like.” But inside I’m also thinking, …but no freaking way am I letting you read my mystery! [*Remember, the goal isn’t: “Let’s see what a random member of the public thinks of this manuscript.” Who cares? We want to know what a likely reader might think of it.] All of which means, when you find an intelligent, genre-conversant, empathetic beta reader… treat them right! I’m talking ‘chocolates and wine’ right. Because they’re a rare and wonderful thing. Happy writing!

0 Comments